Presented at the University of Virginia’s symposium on Robert E. Lee’s Life and Legacy

Presented at the University of Virginia’s symposium on Robert E. Lee’s Life and Legacy

“This is sacred ground. It is a neutral place, no race, color, religion should be mentioned here.” This is how one person responded to a National Park Service survey which asked visitors to Arlington to assess the relevancy of slavery in properly interpreting life at the home of Robert E. Lee. Another visitor responded that slavery should be taught “only in schools” and another individual seriously suggested that “race has no place in the historical discussion and presentation of a slave plantation.” Across the Potomac River in Maryland, the newest Civil War monument to grace the town of Sharpsburg is of Lee on Traveler and includes the following at its base: “Robert E. Lee was personally against secession and slavery, but decided his duty was to fight for his home and the universal right of every people to self-determination.” I have no doubt that such a belief would have been news to Lee’s slave Wesley Norris.

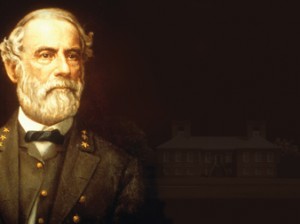

The fact that such views continue to be embraced by Civil War enthusiasts is worth exploring if for no other reason than that it may tell us something about Lee’s relevance at the beginning of the 21st century. In the case of Lee I suspect that our defensiveness about race and slavery is a symptom of a broader resistance to anything that challenges our ideas of Lee’s moral perfection and ultimately our understanding of the Civil War. As historian John Coski noted in a recent Washington Post interview, “There’s an old saw in the South of a little girl asking, ‘Mommy is Robert E. Lee from the Old Testament or the New?’” I agree with Coski that Lee has been so overly lavished with praise that we have turned him into an untouchable “marble man.” Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock there is no doubt that Lee has come under more serious scrutiny in recent years. Some of the attacks can be dismissed as uninteresting or lacking any scholarly merit. On the other hand, professional historians have introduced interpretive frameworks from psychology, gender studies, political science, and race studies, and although the results have not always held up under scrutiny they have managed to enrich our understanding of Lee’s life, the antebellum south, and the Civil War.

It is not surprising that the increase in Lee studies have brought about a backlash from certain corners within the Civil War community. For many people any challenge to the traditional interpretation of Lee or the Confederacy is tantamount to heresy. Consider the description of a symposium on R.E. Lee sponsored by the Stephen D. Lee Institute in northern Virginia which took place this past spring:

2007 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Robert E. Lee, one of America’s most revered individuals. But opinions are changing in this era of Political Correctness. Was Lee a hero whose valor and leadership were surpassed only by his honor and humanity? Or was he a traitor whose military skill served a bad cause and prolonged an immoral rebellion against his rightful government? To many, Robert E. Lee is a remote figure, a marble icon. To others he was simply a great battlefield commander. But Lee was much more; his character shines brightly from the past, illuminating the present. The Symposium will cover Lee’s views on government and liberty, his humane attitudes toward race and slavery, Lee and the American Union, Lee as inspired commander and his relationship with the Army, Lee as a Christian gentleman, and the meaning of Lee for today.

It is difficult to imagine how a serious historical discussion is supposed to take place when the terms of the debate are framed around such meaningless concepts as “hero” and “villain.” The above description, however, is symptomatic of the difficulty that characterizes much of the discourse surrounding Lee’s life and legacy.

We’ve seen signs of this over the past five weeks. I was struck by Bob Krick’s opening talk and the defensive posture which colored his presentation. Krick’s view of Lee differs little from the traditional view of Douglas S. Freeman and he seems to find nefarious motives behind historians who deviate from it. In recent talks he has referred to such historians and their scholarship as “anti-Lee”, “psychobabble” or “revisionist” without any attempt at actually analyzing their claims. At one point in his talk Krick suggested that if you truly want to understand Lee than read his own words as if historical understanding begins and ends with a simple reading of documents. Remarkably what Krick failed to acknowledge is that documents such as letters need to be interpreted and often historians disagree over the correct interpretation.

If we are to take Krick at his word than what are we to make of Elizabeth Pryor’s conclusions about Lee in her recent book, Reading the Man, which I consider to be the most thorough study of Lee’s character since Freeman. A quick perusal of the footnotes and bibliography reveal hundreds of personal letters along with other primary sources that contributed to her interpretation of Lee as father, general, and slaveowner. Is Pryor to be characterized as “anti-Lee” simply because her interpretation strays from the traditional view? Is she part of an “anti-Lee” cabal that seeks to destroy everything that is good and moral? I think it is safe to assume that anyone who listened to her talk and/or read her book could not possibly subscribe to such a view, and I suspect that it’s not the content of the interpretation that is troublesome for some it is the very possibility of interpretation itself. If Lee’s personal attributes are transparent in the letters than no interpretation is necessary and if we take this line of thought to its logical conclusion than the job of the historian is rendered otiose.

We are much more comfortable focusing on Lee the soldier. I suspect that most of us could have continued our discussions with Professors Gallagher and Davis for another hour or two. Questions about Lee’s performance on battlefields such as Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Spotsylvania and elsewhere bring most of us right back to the moment that introduced us to the serious study of the Civil War. For me it was an accidental trip to Antietam in 1994 that served as my introduction. We can debate and read endlessly about Lee’s audacity and the decisions that led to some of his most impressive and decisive victories in Virginia. We can recite such moments as the “Lee to the Rear” incident at the Wilderness in May 1864 or his penetrating words about the nature of violence at Fredericksburg in December 1862.

The difficulty we have in discussing Lee’s connection to race and slavery can be extended to cover the Civil War as a whole. We choose to celebrate military leaders without coming to terms with the fundamental social changes that their actions wrought. And we reflect on the minutia of the battlefield completely divorced from their causes and their consequences. It’s as if the armies simply fell from the sky. We prefer to view battlefields as places where white Americans sacrificed for values of equal worth–no blame, no guilt, no right or wrong. In short our national memory of the war is heavy on battlefield heroics and short on the tougher questions of race and slavery which go far in explaining why there was a war at all. The battlefield has the potential to unite white Americans while the issues of race and slavery work to divide or at the least make us uncomfortable. Once again I am drawn to our visitor to Arlington who urges for the protection of “sacred ground.”

I am going to stick my neck out here and assert that neither Arlington, Civil War battlefields nor Robert E. Lee are sacred. Rather they represent opportunities to better understand a traumatic moment in American history that left over 600,000 Americans dead and 4,000,000 freed. If our goal is to better understand the past than we must be willing to ask the tough questions, including questions about Lee, and place our most deeply held beliefs in check. I agree with the historian William Gienapp that the “outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such the Civil War constituted the greatest failure of American democracy.” From this perspective there seems little to celebrate or for that matter venerate. The more we engage in this kind of behavior the less likely we will be willing to explore the tough questions of how slavery and race caused and shaped the direction of the war and its short- and long-term consequences. I welcome the latest scholarship on all aspects of Lee’s private life and military career—the more the better. Not every critical assessment of Lee should be understood as a personal attack on the general or the South or Southern Heritage. Revisionism is not a dirty word; all good history continually revises our understanding of the past as a result of uncovering new information or thinking anew.

Finally, let me respond to our visitor to Arlington. You can keep your “sacred ground”, I want the truth.

Nice speech, Kevin. I agree that Pryor’s book is a winner. I learned so much more about Lee there than I had ever known, and confirmation of some things I suspected, such as his real attitude toward slaves and slavery. But none of that, ultimately, lowered him very far in my esteem. It simply made him more human, more accessible. As you say, “sacred” ground hides so much.

I really agree with the author- I think that we do not need to focus on if he was indeed a villian or a hero, but rather a person who wanted to defend his country. Great job!