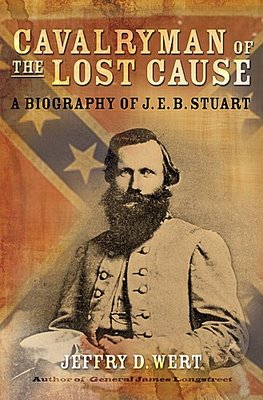

The latest issue of Civil War Book Review includes my review of Jeffry D. Wert’s recent biography of J.E.B. Stuart.

The latest issue of Civil War Book Review includes my review of Jeffry D. Wert’s recent biography of J.E.B. Stuart.

Civil War enthusiasts have come to expect a certain quality of research and writing from Jeffry D. Wert. Since the publication of his first book in 1987, Wert has tackled a wide range of subjects including biographies of John S. Mosby, James Longstreet, George A. Custer, a comparative study of the Iron and Stonewall Brigades, and a history of the Army of the Potomac. His most recent offering is the first full biography of Major General J.E.B. Stuart in twenty years. Despite his prominent place in the Confederate pantheon right behind Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, readers may be surprised to learn that only three biographies have been written about Stuart. Major Henry B. McClellan’s 1885 book, The Life and Campaigns of Major-General J.E.B., is still worth reading for its exhaustive coverage of his military exploits. John W. Thomason Jr.’s 1930 biography, Jeb Stuart is beautifully written, though it is seriously outdated owing to the lack of primary sources. Emory Thomas’s Bold Dragoon (1986) can claim the title of the only serious scholarly study of Stuart, but that in and of itself may have kept it from being read by a more general audience.

Most students of the Civil War want their biographies to be long on battle and campaign coverage and short on interpretation as well as the subject’s pre- and post-war experiences. In the case of Stuart we have only the former to deal with. The vast majority of Wert’s study does indeed focus on the war years and he does so with a firm grasp of the relevant secondary literature as well as an impressive collection of archival material with which to catalog both his performance on the battlefield as well as relations with fellow officers. Wert provides an even-handed assessment of Stuart on the battlefield. While Wert finds Stuart’s “efforts wanting” on the battlefield at Sharpsburg he received high marks for his performance at Chancellorsville in the wake of Jackson’s fatal wounding. As for his exploits around the Army of the Potomac and various raids in the summer and fall of 1862 Wert writes that while they garnered some intelligence these risky expeditions wore out valuable Rebel horseflesh.

No doubt, many will look with interest to the chapters on the Gettysburg campaign and the question of Stuart’s culpability for his decision on June 25, 1863, to conduct a raid around the Army of the Potomac as it marched north in pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia. There are no drawn out descriptions of the meeting between Lee and Stuart at Gettysburg or any serious attempt to answer once and for all whether Stuart’s decision constituted a fatal mistake. According to Wert, “Stuart failed Lee and the army in the reckoning at Gettysburg” though he goes on to note that Lee was “not blameless” (302). Much of the assessment of Stuart’s performance is to be found in the many references to Richmond newspapers as well as the official reports by Lee and other high-ranking commanders. Finally, the decision to deal with this in a concise manner leaves Wert with sufficient space to highlight Stuart’s work in protecting Lee’s army as it retreated back to Virginia and over a swollen Potomac River – an aspect of the campaign that is often overlooked. For this reviewer the obsession with Stuart’s culpability in the Gettysburg campaign is primarily a function of its place in our popular imagination and our never-ending obsession with trying to pinpoint that one factor that held the outcome of the battle in the balance.

In contrast to his military exploits, Stuart’s life beyond the battlefield leaves the reader with more questions than answers. While Wert’s attention to archival sources is admirable they fail to shed any new light into Stuart’s life before the war, including his marriage to Flora Cooke. While Stuart is situated squarely within a generation that was reared on the sectional conflicts of the 1850s, Wert has little to say about his political and racial outlook even though he was involved in suppressing John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry Raid, which set the tone for Lincoln’s election in 1860 followed by the secession of states in the Deep South. More importantly, the author missed an opportunity to explore how the secession of Virginia permanently damaged relations between Stuart and his father-in-law, Philip St. George Cooke. Wert simply notes that Stuart “never forgave his father-in-law for forsaking Virginia” (44).

Such minor criticisms should in no way detract from Wert’s accomplishment. He has managed to strip the many layers of myth from his subject without losing the color that makes Stuart so attractive to students of the Civil War.

Kevin

I was seriously wanting to know what people think about what a good bio of Stuart or anyother figure from the war would need that we don’t do. Having spent many hours in the National Archives going over Stuart’s U. S. Army record, I follow what you are saying. I do a talk about his antebellum career and I believe that seeing what he did in Kansas and being present for John Brown’s raid changed his whole attitude about the country. His letters after 1859 certainly have a different tone from the newly graduated West Point cadet who wanted to serve his country.

Tom,

I’m not sure what your are referring to when you say, “that we don’t do.” I was simply commenting on one book.

Tom,

Thanks for the comment. I don’t want to make too much of this and I think I make that clear in my review. Wert has written a solid book, much like his previous titles. He offers a solid and highly-readable narrative, but at times I just wish he provided a bit more analysis of certain topics. In re: to the Stuart biography the one glaring omission seems to me to be the period before the war and how the secession crisis challenged his family.

Kevin

I too was going to mention Burke Davis 1957 Last Cavalier. I assisted Wert with the latest book and think it well done. Just as a mental exercise, what would you like to see a Stuart bio have in it that none of the previous books do not. I will write it this afternoon. 🙂

Tom Perry

Chris,

I agree overall. As I pointed out in my review I was a bit disappointed in Wert’s level of analysis of Stuart’s pre-war life. This is the one area of his life that is begging for analysis. Of course, the primary materials may not be sufficient for such an analysis.

I think Jeb Stuart has been lucky in his biographers. They have all been quite good and fun to read. Wert is excellent as usual. I also like Burke Davis’s Jeb Stuart book from 1957. Thomason’s illustrations really add to his biography.

Thanks for the review,

Chris

Karen, — Unfortunately, that seems to be the rule in the field of Civil War history, though I suspect that it can be applied to other areas of academia. Sorry about that. 🙂

Note to self: serious scholarship keeps it from being read by a more general audience.

Thanks for an excellent review; I am going to be spending some money this summer on books. I am shocked to learn for all his praise that Stuart has so few books written about him. Finally based on my ROTC Military Tactics Class I agree with my instructor that Jeb made a fatal error in his ride because he left Lee relatively blind to Union troop movements.

Because I haven’t had my caffeine yet 🙁 I read your “three biographies” as “two biographies” and stopped reading to register my complaint. Sorry about that. Mea culpa. I’ll go off behind the house now and fall on my sword in shame…

Why are you “complaining”? I mentioned Thomas’s biography of Stuart in the first paragraph and I believe it to be a very good study.

Pardon me for complaining, but Emory Thomas wrote a biography of Stuart in the 1980s — “Bold Dragoon” — and it was, IMO, very good. Of course Emory at the time was a colleague at Georgia and an occasional beer-drinking companion, so my assessment might not be impartial.