One of the most disturbing aspects of so called accounts of “black Confederates” is the almost complete absence of the voice of the individuals themselves. All too often these men are treated as a means to an end. Accounts all too often reduce complex questions of motivation to one of loyalty to master, army, and Confederate nation. Organizations such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy [see here and here] now routinely publicize the discovery of what they believe to be black Confederate soldiers and in some cases even involve the descendants of these men, who almost always turn out to be slaves. What is so striking is the failure on their part to acknowledge their roles as slaves even in the face of overwhelming evidence. It is important that we see this as little more than the extension of the faithful slave narrative that found voice before the war and reached its height at the turn of the twentieth century. Apart from the ability to influence the general public through websites, blogs, and other social media formats there is really little that is new in the more recent drives to rewrite black Confederates into the past. The war, in the end, had little or nothing to do with slavery and slaves remained loyal throughout.

The extension of this faithful slave narrative in recent years can be clearly discerned in the case of Weary Clyburn. I’ve talked quite a bit about Clyburn over the past few years and in recent weeks. He seems to be the darling of heritage groups like the SCV as well as a favorite of curator Earl Ijames. Consider the recent SCV ceremony that acknowledged Clyburn for his loyal service to the Confederacy and resulted in a military marker. Sadly, this ceremony involved the descendants of Clyburn and gave them the false understanding that he had served in the army. Clyburn was, in fact, a slave; however, that little fact is never mentioned during the ceremony and it is rarely mentioned in most modern accounts. In the midst of all the flags, bagpipes, and praise by SCV speakers and Earl Ijames we learn absolutely nothing about Clyburn himself. What we, along with Clyburn’s descendants, learn is what falls within the boundaries of the faithful slave narrative that has been passed down from generation to generation.

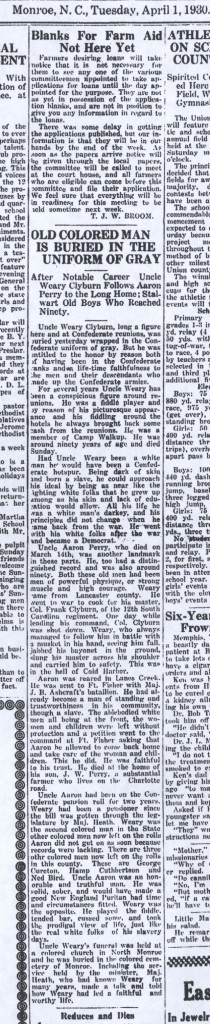

Consider Clyburn’s obituary, which appeared in the Monore Journal on April 1, 1930 under the title, “Old Colored Man Is Buried in the Uniform of Gray.” He was given this “honor by reason of having been in the Confederate ranks and a life time of faithfulness to the men and their descendants who made up the Confederate armies.” The obituary is clear to point out the distinction between being “in” the Confederate ranks and serving as a soldier. Later in the notice the writer does note that Clyburn went to war to “cook for his master, Col. Frank Clyburn of the 12th South Carolina Regiment.” The story of Weary saving Frank on the battlefield is referenced, which fits perfectly in the overall emphasis on faithfulness.

Consider Clyburn’s obituary, which appeared in the Monore Journal on April 1, 1930 under the title, “Old Colored Man Is Buried in the Uniform of Gray.” He was given this “honor by reason of having been in the Confederate ranks and a life time of faithfulness to the men and their descendants who made up the Confederate armies.” The obituary is clear to point out the distinction between being “in” the Confederate ranks and serving as a soldier. Later in the notice the writer does note that Clyburn went to war to “cook for his master, Col. Frank Clyburn of the 12th South Carolina Regiment.” The story of Weary saving Frank on the battlefield is referenced, which fits perfectly in the overall emphasis on faithfulness.

Had Uncle Weary been a white man he would have been a Confederate hotspur. Being dark of skin and born a slave he could approach his ideal by being as near as the fighting white folks that he grew up among as his skin and lack of education would allow. All his life he was a white man’s darkey and his principle did not change when came back from the war. He went with his white folks and became a Democrat.

It’s a remarkable passage and tells us quite a bit about what white North Carolinians chose to remember about Clyburn’s life. At every point, beginning with a reference to “Uncle” is the man himself ignored. He was worth remembering because his actions could so easily be interpreted in a way that would not upset a well-established Jim Crow society by 1930 and at the same maintain their belief in loyal blacks both before, during and after the war. After the war Clyburn was best known for his participation in Confederate veteran reunions; however, he apparently was never acknowledged as a soldier. Rather, he played the fiddle at these events and around area hotels to bring in money.

The tragedy in all of this is that Weary Clyburn’s past did not have to be distorted for it to be recognized and honored. The point that needs to be made is that Clyburn is a hero. He survived the horrors and humiliation of slavery and war and even managed to make it through the height of the Jim Crow South. If that is not worthy of remembering and commemorating than I don’t know what is. Unfortunately, we may never be able to fill in the details of Clyburn’s life, which is itself part of the legacy of slavery and racism in this country. Sadly, Clyburn is still playing the fiddle for various groups and individuals who for one reason or another choose to distort the past.

If you scroll down about half way there is an image of veterans holding a flag that reads “Forrest's Escorts”

Do you really think the black men in the image are fighting for “states rights?” Especially under a man like Forrest?!?!

http://www.militaryphotos.net/forums/showthread…

This, as others here have been saying, is an indication of how the Confederates themselves viewed the blacks “serving” the Confederate cause. There perhaps is an appreciation, maybe even a reverence for the slave on the part of the master, but it is all through the lens of paternalism that so dominated those proponents of slave labor over free labor. “Being dark of skin . . . he could approach his ideal by being as near like the fighting white folks that he grew up among as his skin color and lack of education would allow,” this is not how Confederate soldiers viewed their fellow white soldier; there is more true respect for the Union soldier than shown here. Confederate soldiers, proud of their willingness to fight and respectful of the enemy's, did not extend this respect to the blacks “serving” around them. If the Confederates themselves did not consider the slaves they brought with them to be soldiers, it is difficult to say 150 years later that they were, we do not need to allow our race sensitivities to cloud words written by and for southern/Confederate citizens.

Mr. Levin,

Why won't you face Mr. Ijames in person? It is cowardly to defame and condem him, while you hide behind your keyboard! Are you afraid to see the elephant! My guess is that you know very little about what you claim. You never post opposing comments?? Coward!

Thanks for the comment Dan. I'm not sure what the problem is since I have agreed to meet Mr. Ijames in public. Have you not read the offer by Prof. Brooks Simpson to organize a debate at an upcoming academic conference. Thank you very much for your concern.

It does of course, and sadly, continue further in the records. The pension application including affidavits is completed by the pension board – white men. Mr. Clyburn places his mark on it – as close as we get to his own writing/ words. One addition document further is his death certificate. The informant is none other than Major Will Heath who is mentioned as the minister in the obituary. It strikes me as odd that a family member would not be the informant and instead Heath is (my suspicion is that Heath is Caucasian but I was unable to find him in the census to confirm this). Another series of documents that get us close to Clyburn's own words but are still filtered through a white man are the census records – enumerators were white males and they recorded Clyburn's answers (or maybe a family member's answers – we can not be sure).

It is striking that on the one hand statements are greeted at face value (he always managed to have a gun in his hands) but never any recognition of the lens through which the story is recorded. Nor is there recognition of the purpose of the story. I am reminded of the obituary of Hugh Cale, African American who served in the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction era NC legislature. Many were his achievements but when he died almost destitute, broken by the very Democratic ex-sheriff who wrote the obituary, the lead line was something along the lines of “this well-liked old darky.” Incredible. All of it.

Thanks so much Chris for the contribution. I can't help but come back to the image of Clyburn's descendant who is being handed a Confederate flag as part of the grave site dedication that the SCV sponsored. It's sad to see the family taking part in what is a complete sham and nothing less than a gross distortion of the past.

A man named W.C. Heath makes an appearance at the Union County Confederate monument unveiling and is described as “an honorary member of the Monroe chapter of the UDC.” (Monroe Journal, 5 July 1910).

Reading through the coverage of the event, this passage from then Attorney General (later Governor) Thomas Bickett stood out. He was describing the actions of the women of Union County after the war: “They swore they would not touch pitch, and that pitch would not touch them. Immutable as the rocks, as glorious as the stars they stood for a white civilization and a white race, and today North Carolina holds in trust for the safety of the nation the purest Anglo-Saxon blood to be found on the American shores.” He goes on to mention that the women “refused to be defiled” and that the nation was starting to realize that only the South could deal with the “race problem.”

I know Mr. Bickett did not speak for all the people of North Carolina, but apparently that was his impression of what was going on in Union County during the post-war years. Just a little more context for everyone.

Oh, and Miss Ida Hinds won first prize for the best decorated buggy.

Thanks Tom. I'm sure Chris will find this to be of interest.

I think you nailed it right on the head. The SCV, UDC, and those that believe that there were black Confederate soldiers only bend the truth to meet their needs. They also only use these men, who were servants within the Confederate Army, to advance their belief that there were actual confederate soldiers under arms against the United States Government. I think if they really wanted to use these men, they should put their stories out there using documented accounts to actually prove that they took up arms.

Nice to hear from you Tim. They should do exactly that, but keep in mind that many of these people are simply unaware of how to go about the process of crafting a viable historical interpretation. If you've been following my blog recently you would know that even people trained in archival work seem to fall short. In some cases these stories have plenty of documentary support, but more often than not the documents are misinterpreted or not irrelevant to the specific point that is being made.

The problem is that, while not invisible, these purported “black Confederates” do not appear to be individuals to those who seek to exploit them and their descendants. They are mirrors whose only purpose is to reflect, in as flattering a way as possible, the whites' image.

Exactly my point.