As a quick follow-up to yesterday’s post on Sherman and Civil War memory I thought it might be helpful to cite a passage from William G. Thomas’s new book, The Iron Way: Railroads, the Civil War, and the Making of Modern America

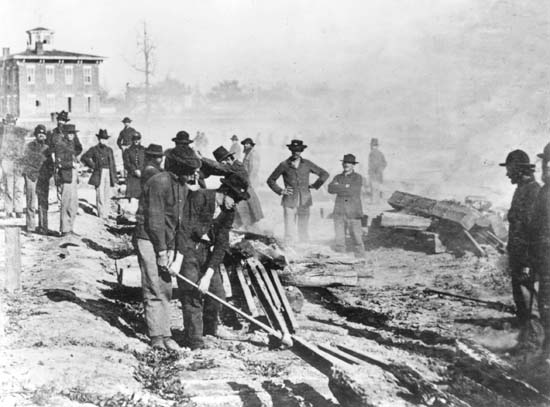

As a quick follow-up to yesterday’s post on Sherman and Civil War memory I thought it might be helpful to cite a passage from William G. Thomas’s new book, The Iron Way: Railroads, the Civil War, and the Making of Modern America. No image of Georgia in 1864 is more iconic than that of Sherman’s men destroying southern rails and turning them into what became known as Sherman neckties. The destruction caused by Sherman’s army almost always eclipses the rebuilding that took place immediately following the war.

Reconstruction of the South in this respect was literally re-construction, a fact long obscured in the era’s twisted history, which the white South remembered long as punishment and subordination, conveniently forgetting the generous terms of their restoration….

No railroad suffered more than the Western and Atlantic (what Wright called the Chattanooga and Atlanta) because of both Union army maneuvers across it and Confederate cavalry raids against it during the Atlanta Campaign in the summer of 1864. The Confederates tore up twenty-five miles of the railroad in a massive raid aimed at disabling the Union’s key supply route. And in an effort to cut off Atlanta from external communication, Sherman just before his November March to the Sea, “very effectually destroyed the road” and gave orders for Wright’s Corps to remove sixteen miles of track between Resaca and Dalton. Yet, after Sherman’s March was completed, Wright’s Corps went back to Atlanta and rebuilt nearly all of the Western and Atlantic, laying down 140 miles of new track and cross-ties, raising 16 bridges, and erecting 20 new water tanks. Close to $1 million in construction labor and $1,377,145 in new material were expended on the Western and Atlantic before turning it over to the state of Georgia and its original corporate officers in September 1865. (pp. 183-84)

According to Thomas, in less than one year rail service in the South had been largely restored. The book details the rebuilding that took place throughout the South toward the end of the war. I highly recommend it.

The book received an honorable mention from this year’s Lincoln Prize.

Sherman’s invasion was really the final blow to an economy that was already crippled. Inflation in Georgia by early 1864 reached unbelievable levels.

Like you point out, the Union Army rebuilt the railroad quickly in the post war era. However, those same railroads will be the heart of unbelievable corruption in Georgia. Of course that is an issue all on its own. Great recommendation though, putting it in the Amazon shopping cart.

Memo To General Sherman regarding the rebuilding of the South after the Civil War from the office of the President:

“You didn’t build that.”

While the destruction of railroads is emblematic of the march, I would say that food and agriculture played a more important role for both the army and those civilians within the path of the campaign. As one historian has speculated (and whose citation I can not remember at this time,) a dissertation could be written by calculating the value of the fence rails destroyed by the army for it’s cook fires and comfort.

That’s a sword that cuts both ways. Most soldiers’ memoirs mention “foraging” repeatedly, often with great nostalgia about how well they ate as a result, contrasted to their regular army rations. In the case of Confederate soldiers, who campaigned almost entirely in the South, all those pigs and chickens and corn stocks were “liberated” from Southern civilians. Even when supplies were purchased from locals, it was usually with scrip that proved worthless. So while I can understand the anger of Southern civilians directed toward Sherman’s (and other Union commanders’) “bumming,” it’s troublesome that he’s condemned for activities that Confederate troops had been practicing, at perhaps a slightly lower intensity, for years in some parts of the Confederacy.

Andy (if I may), I completely agree. There are civilian accounts written in 1864 that describe the actions of Wheeler’s cavalry as more destructive than the actions of Sherman’s men. Couple that with the long-term foraging, seizure, tax-in-kind conscription of resources, and a picture develops of fractured Confederate agriculture in Georgia and other southeastern states.

I’ve also been fascinated by the extremity that some farmers and planters took a libertarian definition of individual rights in the seceded states. Howell Cobb, one of the most vocal proponents of secession, declared that the government and local pressure would not prevent him from determining how to run his plantations when the calls came for a cotton fast and the production of staple crops as patriotic duty. Cobb openly planted as much cotton as he could, need be damned. Couple that with the reports of farmers who planted a covering fringe of corn to mask cotton production inside their fields, and the picture of a South that switched from commodity to staple production to support the war effort disappears.