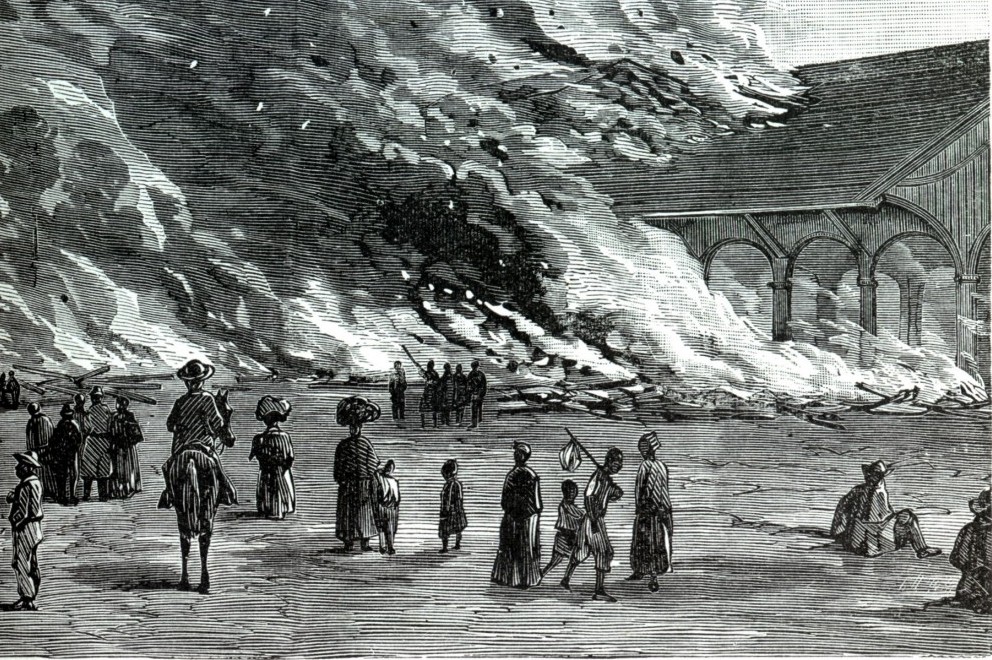

In re-reading a section of Anne Rubin’s new book about Sherman’s March I came across a couple of paragraphs that touch on some of the concerns that I’ve expressed about the extent to which we have applied the lessons of recent wars to Civil War veterans. Rubin hones in on the dangers of doing so in regard to how Union veterans remembered the march and their interactions with Southern civilians.

Nor did they use memoirs or fiction to pour out their hearts and souls, expressing shock or trauma at what they saw or did. Today we are accustomed to stock war stories with their mix of crusty old generals, fresh-faced young recruits, and eventually the traumatized veteran, forever haunted by the things he saw and did… Recently, we’ve seen the twenty-first century version, with a host of new memoir s of Gulf War service. In April 2008, a Rand Corporation study announced that one in five service members who served in Iraq or Afghanistan reports symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder or major depression. We think that soldiers are forever scarred by their service, especially when they are asked to make war on civilians.

But what of their nineteenth-century counterparts? Analogies have often been made, albeit imperfectly, between the Vietnam War and Sherman’s March. James Reston’s 1986 work, Sherman’s March and Vietnam makes the connection most explicitly, arguing that Sherman was the metaphorical father of destructiveness and that connections can be drawn between the soldiers of the 1860s and 1960s. In Reston’s words, “the wanton violence of Sherman’s bummer and Westmoreland’s grunt differs as looting differs from killing, but neither time nor morals are static. Stealing the jewels from a peasant’s hooch in Vietnam would be precious little crime today. The patterns of behavior in both armies were encouraged by the official policy and extended the rules of permissible conflict in the same degree.” So, if Vietnam (and now Gulf and Afghanistan) veterans have been troubled by their service, and indeed, the vast majority of their writings seems to indicate that they were, one might be able to assume that Sherman’s veterans felt a similar sort of, if not remorse, at least discomfort. (p. 97)

According to Rubin, however, they did not. Perhaps as the author suggests these veterans remembered in a “celebratory fashion” because they were convinced that they had won the war. Of course, the same individual could just as easily exhibit symptoms of what we now call PTSD or struggle in any number of ways readjusting to life as a civilian. Again, my interest here is not in discounting recent attempts to apply the lessons learned in recent wars, but rather in remaining attentive to how we apply them.

If you drill down into the minutiae of local histories and newspapers, in the late 19th century there are a few accounts of communities in which there were homeless men and men living rough within wild patches of land on the urban fringes who were civil war veterans who could not settle down to civilian life. Before riding the rails became a depression era phenomenon, “tramps” and “vagabonds” in the late 19th century were sometimes veterans. Ex-service organisations sometimes picked up the tabs for their funerals.

Jim Marten’s book _Sing Not War_ should have mentioned before now, but it’s excellent on these men.

Brian Jordan briefly mentions it as well.

John De Forest was combat veteran from CT who was quite a cynic and realist (just read his book about his experiences as a Freedman’s Bureau officer) and also an accomplished writer. Yet in 1867 he wrote this nostalgic passage that follows a description of harrowing combat in his novel “Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Seccession to Loyalty.” (Fort Winthrop is a fictionalized version of the successful defense of a beseiged river fort in the Red River campaign. The town referred to is probably New Haven). Maybe De Forest suffered from PTSD, but you would never guess it from this:

“Such was the defence of Fort Winthrop, one of the most gallant feats of the war. Those days are gone by, and there will be no more like them forever, at least, not in our forever. Not very long ago, not more than two hours before this ink dried upon the paper, the author of the present history was sitting on the edge of a basaltic cliff which, overlooked a wide expanse of fertile earth, flourishing villages, the spires of a city, and, beyond, a shining sea flecked with the full-blown sails of peace and prosperity. From the face of another basaltic cliff two miles distant, he saw a white globule of smoke dart a little way upward, and a minute afterwards heard a dull, deep pum! of exploding gunpowder. Quarrymen there were blasting out rocks from which to build hives of industry and happy family homes. But the sound reminded him of the roar of artillery; of the thunder of those signal guns which used to presage battle; of the alarums which only a few months previous were a command to him to mount and ride into the combat. Then he thought, almost with a feeling of sadness, so strange is the human heart, that he had probably heard those clamors, uttered in mortal earnest, for the last time. Never again, perhaps, even should he live to the age of threescore and ten, would the shriek of grapeshot, and the crash of shell, and the multitudinous whiz of musketry be a part of his life. Nevermore would he hearken to that charging yell which once had stirred his blood more fiercely than the sound of trumpets: the Southern battle-yell, full of howls and yelpings as of brute beasts rushing hilariously to the fray: the long-sustained Northern yell, all human, but none the less relentless and stern; nevermore the one nor the other. No more charges of cavalry, rushing through the dust of the distance; no more answering smoke of musketry, veiling unshaken lines and squares; no more columns of smoke, piling high above deafening batteries. No more groans of wounded,[Pg 346] nor shouts of victors over positions carried and banners captured, nor reports of triumphs which saved a nation from disappearing off the face of the earth. After thinking of these things for an hour together, almost sadly, as I have said, he walked back to his home; and read with interest a paper which prattled of town elections, and advertised corner-lots for sale; and decided to make a kid-gloved call in the evening, and to go to church on the morrow.

——————————————————————————

In the Civil War soldiers on both sides were less than enthusiastic about being involved – probably true of all wars. Would PTSD symptoms increase or decrease depending on whether one considered it a ‘just’ campaign? Does someone convinced they’re fighting for a moral cause feel more – or less – distressed by brutalities of war, than one who fights for political, racial, or economic reasons? Does offense versus defense make a difference?

I think it’s clear that whatever one wishes to call it (PTSD, shell shock, combat exhaustion, etc.), some combat veterans suffer from negative effects of their experiences. Furthermore, exposure to artillery fire seems to be especially traumatic, since from the perspective of the individual soldier, it is beyond any sort of recognizable human agency–unlike, say, actual hand to hand combat in antiquity–and the potency of missile weapons may help explain the historic inability of settled civilizations to cope with mounted nomads coming out of the Eurasian steppes armed with composite bows. All that being said, the problem with using categories like PTSD is that historians of psychology have shown how ideas like “trauma” are themselves contingent on historical and cultural circumstance. This is the potential danger of assuming the concepts of modern psychology are universally applicable to historical actors, akin to the ballistic qualities of the rifle-musket. This was the problem, for example, with how Drew Faust in past work attempted to apply WW2 military psychology to Civil War soldiers.

I actually think there’s powerful work waiting to be written about the relationship between military service and mentally “off” behavior–particularly the propensity toward alcoholism and cantankerous behavior, both in the Old Army and during the Civil War. I think a lot of this has to do with an Honor-driven culture preoccupied with reputation and status, but I also wonder more and more if this has a lot to do with military service (even while in camp) is just really, really difficult, and people don’t always cope well–the sort of thing we would associate with things like PTSD, but Victorians would ascribe to sinfulness and demoralization. They drink, they fight over preposterous things, they indulge in vices their faith and culture will lead to damnation, etc. And is it surprising, considering the circumstances? And, of course, sometimes in military terms, they fail– but, on the whole, and even in battlefield defeat, Civil War military organizations still cohere and function, despite all the problems. Contrast this to the Iraqi Army’s recent disasters, or the Nigerian Army’s inability to even pretend to be able to deal with a group like Boko Haram.

I think that some scholarly work starts to do some of this (even work that’s quite old–Bell Wiley talked for example about rates of venereal disease among Civil War soldiers, and Bruce Catton also talks about the disorderly behavior of soldiers in the Army of the Potomac), but what we’d really need is a historian who can both use and escape the intellectual confines of modern psychology to look at Civil War soldiers, including a fine grained understanding of both operational and cultural circumstance.

As for Iraq/Afghanistan, here are some major differences between combat there and the Civil War. Civil War soldiers still fight elbow-to-elbow for the most part, which is an important cohesive element, in contrast to what seems to be the most taxing element of recent wars–driving around waiting to be blown up by an IED. But even this is a problematic generalization–for example, participating in commando raids at night, with the potential of close quarters combat and actually killing someone face to face, is going to be a different kind of experience than foot patrols while dodging IEDs and moving into firefights with Taliban at a distance. Or what happened at Wanat in Afghanistan, where a combat outpost was nearly over-run, or of clearing an urban environment like Fallujah. I’m not saying trauma doesn’t exist–I’ve seen it myself–but the current story of American wars is, like everything else, far too complicated to be reduced to one concept. And, indeed, Civil War soldiering had within itself a wide variety of experience. Anyhow, one of the problems the current Army and Marine Corps is having is retaining junior officers who’d actually *prefer* more deployments than peacetime garrison duty. I’ve seen this myself in my own former students.

I didn’t mean to imply there was a change in attitudes. “Shellshock” was the commonly recognised name for trauma suffered by many WW1 soldiers, and there were many shell-shocked WW1 veterans around after WW2, but WW2 veterans were rarely referred to as shell-shocked.

I think that there was more awareness of at least the symptoms of PTSD here in the U.S. after World War II.

There was a film called “The Best Days of Our Lives” released in 1946 with what is now considered a classic PTSD flashback. It described the difficulties of three servicemen returning from the war. The film by William Wyler has been called “the most honest and straightforward look at PTSD to come out of post-WWII Hollywood.” It was the seventh highest grossing Hollywood film before 1950 and it won seven regular and two special Academy Awards. Although the term PTSD was not used, the film raised awareness of the suffering of many servicemen.

The film was popular among many vets, who saw it as more realistic than the heroic or buddy war films that were popular during the war years.

Only because the doctor’s terminology had shifted from “shell shock” to “battle fatigue.”

I think Mat McKeon has nailed it wrt Sherman’s march.

More generally, you don’t have to go all the way back to the Civil War to find absence of PTSD etc. In Britain, and I imagine it’s the same in America, there was never any suggestion that veterans of WW2 were traumatised in large numbers (different for WW1, of course). A few years ago, police officers w2ho had to deal with a disaster at a football ground complained of being “traumatised”. SFAIK the soldiers who liberated Belsen didn’t complain of, or actually experience, trauma, altho they were of course deeply and unforgettably shocked.

When I was growing up, several of the World War II veterans in my little neighborhood most certainly returned from the war with “battle fatigue,” and everyone knew it. Two of my own relatives suffered until they died in the early 1980s. I see no reason to think that my small town neighborhood was an anomaly. But it was only discussed in whispers and asides, because PTSD-like symptoms still were seen as shameful and unmanly. What you interpret as absence was in fact silence. Let’s not strap that shame back on current vets by suggesting that there’s something weak about them in comparison to their great-grandfathers. There isn’t.

See “Physical and Mental Health Costs of Traumatic War Experiences Among Civil War Veterans” on line at http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=209288

Somewhere I have seen figures indicating 20-30% of combat soldiers suffer from PTSD, a figure consistent over time and wars from the Civil War to Iraq. What is different about the late 20th, early 21st centuries is a recognition of an obligation on the part of the government to take care of these men.

I do wonder if the presence of the “West” in the post-Civil War America provided an outlet for restless veterans of both armies not available in the World Wars and alter.

One of my uncles, who died at a young age when I was still a toddler, saw combat in the last months of the war with the 101st Airborne. I never really knew him, but he told other family members that many employers, post-war, wouldn’t hire veterans who had been in combat, because they didn’t want to risk having to deal with the vets’ psychological issues. Returning veterans, my uncle claimed, learned very quickly to tell prospective employers that they’d spent the war stateside or in some quiet, out-of-the-way post overseas.

Maybe British veterans are just more “manly”, but the effects of stress syndromes related to combat was a concern of the U.S. VA after World War II and several studies were commissioned on it. The earliest, in 1947, described “traumatic

war neurosis”.

Here is the description of one study from 1960:

“Dobbs and Wilson (1960) reported an interest

ing experiment that foreshadowed current labora

tory studies on the psychophysiological correlates

of PTSD. They exposed WWII veterans with com

bat-related psychiatric symptoms, healthy combat

controls from WWII and the Korean conflict, and

nonveterans to audiotapes of combat sounds. Com

bat controls showed greater pulse, respiration, and

EEG responsiveness to the stimuli than did

nonveterans. ”

See here for more: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/newsletters/research-quarterly/V2N1.pdf

Why should the soldiers of Sherman’s march suffer from PTSD? The march was the easiest thing they had to do in the army. They moved rapidly, beat the daylights out of their farcical opposition, got to destroy a bunch of stuff: which is tremendous fun. They won the war, saved their country and ended slavery. What’s not to love?

The brutal combat in battles like Kennesaw Mountain, or around Atlanta itself, that was a different story.

Currently we like to “medicalize” things, using the language and framework of illness. Let’s be careful about “back projection.”

It is not surprising Sherman’s men felt little remorse regarding their interactions with civilian populations. Historians often overlook one of the chief reasons war came to begin with, which was an intensity of feeling between the sections which would find no release short of war. Sherman’s men were not fighting in a foreign country with ill defined objectives. They were at war with a section, and its people, who they regarded as destroying something which belonged to them, namely the Union itself. There is no fight, and no grievance held longer, than a fight within a family. I say this not to justify their actions, just by way of a possible explanation for why they did not regard these interactions in a negative way.

Another answer can be found in the order of battle for the March to the Seas. Sherman’s troops were westerners (Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio mainly). War in the west was quite a different thing from war in the east. One has only to read about the events early in the war in Missouri to recognize that western soldiers were used to seeing civilians treated by both sides much differently than in the east.

Finally there is Sherman himself. His army was a reflection of him and his attitudes. His troops certainly did not operate outside his own view of war, so they would not have been likely to viewed their actions through any lens beyond their leader’s.

Returning to my original point, having been brought to a boil prior to the war, the men who fought for both sides were not always the picture we have of happy warriors afterwards reaching across stone fences at Gettysburg. And it is that intensity of feeling which probably dampened any moral ambiguity men on either side felt regarding their actions during the war.

I’ll leave it to people with better expertise than I to reach a conclusion, but it seems to me the notion of ‘triumph’ is important. The veterans of VietNam/Afghanistan/Iraq fought wars that were largely unsuccessful and/or unpopular, so there is a fundamental disconnect with a view of them as ‘heroes’ of conflicts that were either morally wrong, or simple military failures, or both. The Union veterans, by contrast, were the victors of the war, and honored by their government and most of their civilian contemporaries as such. Surely the high rate of PTSD for contemporary veterans has some relation the public view of their efforts as failures, as opposed to the successes of Union Civil War veterans,

I wonder how the presence of GAR Halls in the north, as well as the fact that most of the Boys of ’61 (and later) came from the same town/county. Everyone you knew was a neighbor and went through the same circumstance.

I think this is another aspect to think about. Thanks, Bob.

Stuart McConnell’s work on the GAR suggests that veterans used their meetings for mutual support and healing even as they closed ranks and kept non-veterans at arm’s length. Gerald Linderman likewise posited a fifteen year period of veteran “hibernation.” Linderman is often dismissed for his small research base, but too easily, I think. Over the years I’ve found him to be right more often than not. In the end both suggest that a lot of vets came home scarred and turned to each other.

As to the larger point I do agree that we could go too far down “the dark turn” and assume that most vets came home as victims. But by the same token, we can go too far in continuing to hope, without much research, that they didn’t. Beyond the anecdotal, or shallow comparisons, I don’t think we know. I also confess that I don’t understand resistance to asking the question because a modern war stimulated the inquiry in the first place. When has Civil War scholarship not been shaped by questions generated from our last war?

I completely agree, Ken. What we need is balance between using recent wars to ask new questions and understanding its limitations.

Brian Jordan does a pretty good job of challenging Linderman’s notion of a “hibernation” but I will leave that for you to decide as I assume you will read it.

The only Civil War memoir I can think of that approaches classic accounts of service in the World Warr, Vietnam, or more recent conflicts in terms of bitterness and disillusionment is Frank Wilkeson’s “Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac,” reprinted as “Turned Inside Out.” Wilkeson writes as though he is determined to push back against the self-congratulatory memoirs of the 1880s, but there is evidence that he embellished his own account as well.

I think it’s worth distinguishing here between the psychological costs of war and memory. There’s no reason a veteran of any conflict couldn’t simultaneously grapple with the scars of war (PTSD, most commonly) while also adopting and promoting a triumphant narrative. Union veterans’s programs often contained content that celebrated reunion and emancipation while at the same time memorialed fallen comrades. If the newspapers are to be believed, veterans spent a lot of time both singing and crying when they got together. Vietnam was a different sort of conflict, but I think we can see the same pairing of pain and triumph in the popular culture of the late 70s and early 80s.

Nice to hear from you, Chris.

There’s no reason a veteran of any conflict couldn’t simultaneously grapple with the scars of war (PTSD, most commonly) while also adopting and promoting a triumphant narrative.

I completely agree, which is one of the points made in the post. Looking at the Civil War through the lens of more recent wars is unavoidable and can even be helpful. My concern is more with balance.

I didn’t mean to imply that we weren’t on the same page, I was just trying to expand on your point. I think I was, in part, trying to say that the way Sherman’s men reacted to their experiences wasn’t entirely exceptional. Horror and triumph always go hand in hand in war and I think veterans have always struggled to balance those two things. Or I’m just rambling because it’s too early on a Saturday morning to think about stuff like this.

Thanks for the clarification. 🙂

Its like sex Kevin. They didn’t write about it, so they obviously did not have it.

And yet the population increased.

Go figure.

Hi Pat,

I understand that Victorian-era men were less likely to share certain aspects of their inner lives with others, but at the same time we ought to be open to the possibility that these same men may have experienced war in ways that diverge from soldiers today.

I have worked with thousands of veterans and refugees from modern civil wars who never heard of ptss and whose cultures demand that men not show weakness. Their children seem completely unaware of the suffering of these men. And yet, in interviews, they often confess to the symptoms associated with ptss.

Someone writing about them 150 years from now, who did not have my notes, would conclude that unlike Americaqn-born veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, the veterans of civil wars in Latin America did not seem to suffer ptss.

BTW, I do recognized that Civil War soldiers did have a different experience. War was episodic, not constant. On the other hand, modern soldiers rarely see thousands of dead men lying on a field, kill with their hands, of watch friends suffer and die without medical care.

Let me first say that I am no expert on any of these issues. As I’ve said all along I am not in any way denying that such conditions exist and very likely exist in all wars. Thankfully, we have a language in place to better diagnose and even begin the process of recovery.

War was episodic, not constant. On the other hand, modern soldiers rarely see thousands of dead men lying on a field, kill with their hands, of watch friends suffer and die without medical care.

One of the problems I had with Chandra Manning’s fine study of Union soldiers and emancipation was that she was not sensitive enough to time and place. If you remember part of her argument was that Union soldiers became convinced of the necessity of emancipation much earlier than previously thought – as early as the end of 1861/early 1862. To whatever extent this is true may have everything to do with which army is being examined. Certainly soldiers serving in the armies out west would have come into contact with slaves much earlier and in much larger numbers than the Army of the Potomac in Virginia. I guess what I am suggesting is that perhaps we need to be more sensitive to local conditions when addressing questions about the long-term impact of “the trauma of war” on Civil War veterans.

I wonder if we need to acknowledge, say, the difference between being on the march with Sherman through Georgia and the Carolinas with little actual fighting and going through the Overland and Petersburg campaigns in Virginia.

I think that is correct.

Late recruits/conscripts who only served with Sherman in the final phase of the war would have less traumatic experiences than vets who fought in the Overland Campaign and at Petersburg. It would perhaps have less to do with notions of “triumph” and more to do with duration and intensity of combat, personally witnessing or being in fear of death, etc.

Thanks for the follow up.

It would perhaps have less to do with notions of “triumph”…

Why do you believe so?

Wondering about other differences.

* Volunteer v. Draftee

* Reenlistment

* Intensity of specific battles

* Belief in Cause

What else?

PTSS, often called PTSD, is not related to the “bravery” or “commitment to a cause” of the soldier. That is an outdated view that sought to blame the sufferer for his suffering. PTSS is a reaction to trauma, and particularly to repeated traumatization. The committed abolitionist could suffer it just as much as the ambivalent draftee.

The fact that different people may react differently to the same levels of trauma is typically unrelated to the factors you list.

Also, many people who suffer trauma and appear to cope well with it immediately afterward will develop PTSS later in life either as a reaction to a life event or to news of a new conflict. Many of my clients had symptoms after 911 for example. They often described flashbacks to El Salvador or Peru.

Here is the Dept. of Veterans Affairs description of this manifestation of PTSD:

Many older Veterans find they have PTSD symptoms even 50 or more years after their wartime experience. Some symptoms of PTSD include having nightmares or feeling like you are reliving the event, avoiding situations that remind you of the event, being easily startled, and loss of interest in activities. There are a number of reasons why symptoms of PTSD may increase with age:

-Having retired from work may make your symptoms feel worse, because you have more time to think and fewer things to distract you from your memories.

-Having medical problems and feeling like you are not as strong as you used to be also can increase symptoms.

-You may find that bad news on the television and scenes from current wars bring back bad memories.

– You may have tried in the past to cope with stress by using alcohol or other substances. Then if you stop drinking late in life, without another, healthier way of coping, this can make PTSD symptoms seem worse.”

Here is a link to info on PTSS/PTSD

http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/types/war/index.asp

I think your point about distinguishing between the type of experience being remembered or memorialized is an important one. Veterans loved to sing “Marching through Georgia” which is nothing if not triumphant. On the other hand, they almost never sang songs about actual combat.

Rubin does a really good job of exploring the ways in which Sherman’s men justified or downplayed many of the more violent encounters with civilians – experiences that did not make it into their songs and other memories.