One hundred and fifty years ago Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment and paved the way for ratification by the states. With a roll call and signatures roughly 240 years of slavery ended and yet as a nation we do nothing to publicly acknowledge this milestone. It’s striking given our collective embrace of a narrative that places the United States at the forefront of freedom. Even Steven Spielberg’s celebratory narrative about the build-up to this very moment in Lincoln has done little to increase awareness and interest. Why do we look beyond this moment?

I don’t have any firm answers, but the tension I often feel in my own teaching of this important event perhaps offers a few clues. On the one hand there is something quite remarkable about the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. You would have been hard pressed to find Americans in 1861 predicting the end of slavery and that same year Congress passed a never-ratified amendment protecting slavery from future amendments. Lincoln backed it. Even in 1862 it is easy to imagine how a military victory might have resulted in a reunited Union with slavery largely intact. From this vantage point the end of slavery in 1865 appears to be nothing less than an achievement.

But it’s the way in which slavery ended and the issues it raised for the entire country that create questions that few of us are equipped to deal with or willing to confront. So, on the one hand I want my students to appreciate the extent to which the end of slavery was unexpected from the vantage point of 1861 and at the same time they need to come to terms with how it ended and the consequences for what will come later in the course.

If we are honest, we have to acknowledge the role of military failure and the interaction of armies and slave populations and not a moment of moral clarity that led to emancipation and the Thirteenth Amendment. In other words, it was the grinding nature of the war itself that undermined the institution of slavery. Military failure and the goal of preserving the Union ultimately demanded the assistance of former slaves and free blacks. Ta-Nahesi Coates is fond of pointing out that it took ‘black men shooting white men in the face’ that brought about the end of slavery. It’s an important point and one that Carole Emberton more carefully explores in her most recent book. State sanctioned violence involving African Americans may have helped to save the nation, but it reinforced long-standing fears surrounding the arming of large numbers of black men.

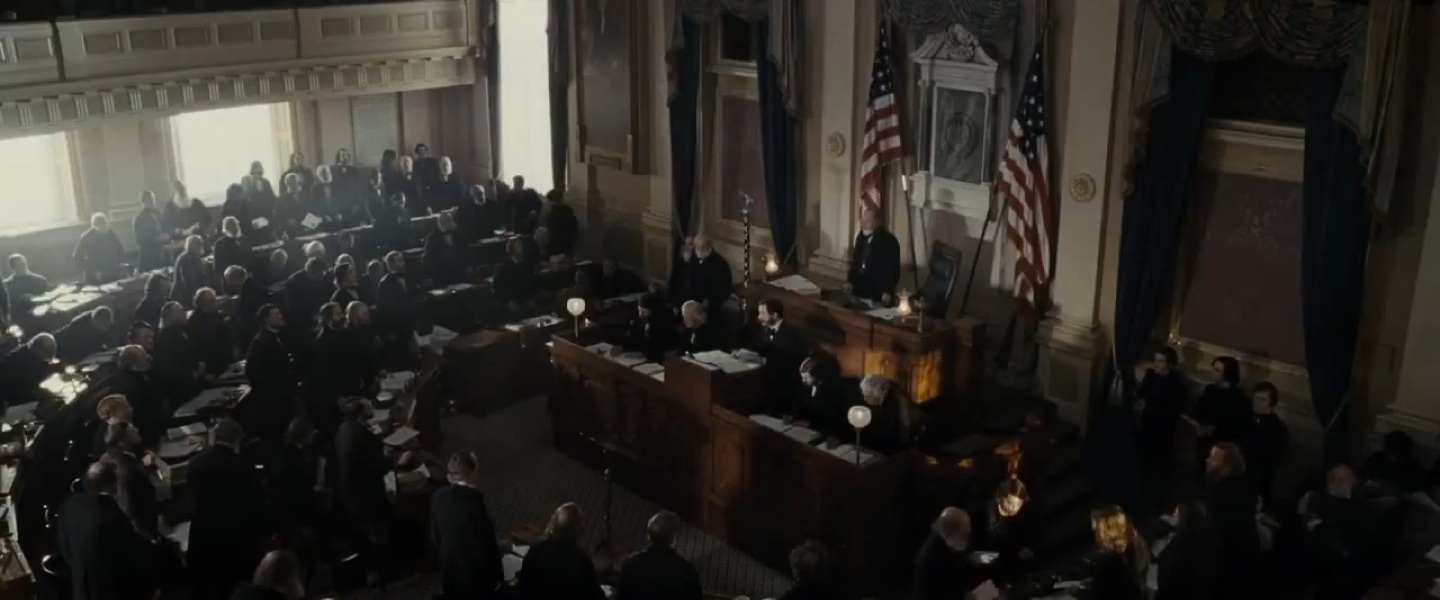

The gradual erosion of slavery by the middle of the war also raised profound questions that challenged a nation’s commitment to white supremacy. I always have my students read and analyze Democrat Samuel Cox’s 1862 speech in Congress in which he worries about the ‘Africanization’ of his home state. [To its credit, Lincoln offers a bit of this language in some of the debate scenes.] The speech beautifully connects my students to the violence of Jim Crow throughout much of the South as well as urban violence during the “Great Migration” and beyond.

Let me be clear that I am not trying to minimize the importance of the end of slavery in this country. Certainly, recent scholarship shows that the Civil War generation, including many men who donned the Union blue believed that bringing an end to slavery constituted an important moral victory even if they could not embrace the possibilities surrounding racial equality. While Americans did not see this distinction as a problem to how they assessed the outcome of the war, we find it difficult to get around. We struggle with acknowledging the end of slavery in light of the many problems that still beset this nation when it comes to racial justice. Any celebration is tainted by a long history of racial violence that stretches to Ferguson, Missouri and beyond. We want to fit this moment into the neat narrative package of “American Exceptionalism,” but it never quite sticks.

Of course, there is room to commemorate and even celebrate the end of slavery in the United States. We can embrace the remembrance of the end of slavery even as we acknowledge the “unfinished work” that must be carried out by each generation. Isn’t that what this country is all about? At least that’s what I try to impart to my students.

Happy Thirteenth Amendment Day!

I first heard about Juneteenth in the 1980s in Oakland, California, where it was celebrated. Lots of the black people in Oakland have their roots in Texas, which I suppose explains why Juneteenth took root in Oakland. It also explains why you could get fabulous Texas-style bbq in Oakland, yummm….

I love the idea of a national holiday celebrating the end of slavery, and my vote would be for Juneteenth. It wouldn’t need to necessarily be a paid vacation day, but I’d like to see it widely observed, and commemorated officially. Part of why June 14 would be apt is the proximity to the 4th of July.

Below is a link to many of the activities and celebrations that Hofstra Unversity has arranged for the observance of black history month. Below that, again, is a link to the Senior, ooops, forgive me, to the all-white Senior Adminstration at Hofstra University. Looks like you need to be in Hofstra University’s face, and I mean in their face big. The all-white Hofstra University administration has no right to manage the celebrations of black freedom and black heritage in this way.

http://www.hofstra.edu/studentaffairs/omisp/omisp_blackhistmonth.html

http://www.hofstra.edu/About/Administration/administration-senior.html

I didn’t realize “whites” were not permitted to celebrate “black freedom”. You must have despised that particular scene in the movie “Lincoln”, where “whites” were not only observed actively managing “black freedom”, but whites were also depicted as wildly celebrating “black freedom” in the House of Representatives and throughout the streets of Washington D.C. You imply that my ancestors and countrymen were wrong for managing and celebrating in such a manner, and that their posterity is likewise wrong for continuing to celebrate. You are doing precisely what I described in my original post.

Thanks for making, illuminating, and emphasizing my point in the grandest manner possible.

I have no idea who your ancestors were nor do I care. Sorry, but what ever you are trying to work out is lost on me. Take care.

And I, in turn, was referring to you apparent lack of confidence in whites to manage things properly. As for the merits of your argument, “Juneteenth” fails as a date to celebrate freedom because as of “Juneteenth” slavery was very much alive, well, and also perfectly legal in the United States. Why on earth would blacks celebrate freedom when their brothers and sisters were still under the lash of ol’ massa in Kentucky and Delaware?

Why would “whites” need to “manage” the celebration of black freedom? When you ask me “Why on earth would blacks celebrate freedom” on Juneteenth, you imply that my neighbors and friends are wrong for celebrating on the day that they and their families have traditionally done so. You are doing exactly what I was talking about in my first comment.

Thanks for making my point.

RE: “Why on earth would blacks celebrate freedom when their brothers and sisters were still under the lash of ol’ massa in Kentucky and Delaware?”

The historian Mitch Kachun has made the observation that, most celebrations of emancipation and abolition have evolved based on localized events and memories of how slaves gained their freedom. Hence, in Richmond, VA, people of African descent used April 3rd as their emancipation day – this is the day that the Union army came in (with black Union soldiers at the forefront, by the way) to liberate the city. It was a special event that was unique to them and their locale.

So, that was Richmond-based day of commemoration. Juneteenth is a Texas-based day of commemoration. And there are others that are unique to their locale. It’s not like people were ignoring why happened to others, it was more a case of memorializing the specific events that affected their communities.

An attempt was made, in the 1940s, by a group of African Americans to have a national day of observance, which became National Freedom Day. It failed to catch on. Juneteenth did. The rest is, as they say, history

There wasn’t really a national day if observance

Oh, I wouldn’t worry too much about the whites mismanaging or ruining the Juneteenth Seqsqui too much. Sometime the whites do good work. Take for instance, Hofstra University. The entire Senior Administration is white, and from what I understand, it’s a pretty good school.

http://www.hofstra.edu/About/Administration/administration-senior.html

I was referring to the Village of Hempstead’s Juneteenth. I am not aware of any large Juneteenth at Hofstra.

I would just note, since I work in a largely African American village, that the end of slavery is commemorated every year on Juneteenth, not January 31. Even my girlfriend’s mostly white church celebrates that June day. If there is a push to mark the end of slavery, Juneteenth would be the most appropriate. Making it some other day just disempowers the black community.

As we saw last year with the Cushing Medal of Honor, nothing attracts attention to something Civil War oriented like the involvement of President Obama. If folks want this year’s 150th Juneteenth to get national attention, push for Obama to keynote a national celebration.

As I have pointed out elsewhere, the Civil War commemorative crowd is overwhelmingly white and I would guess is hardly unified in welcoming Obama’s participation. I hope the Juneteenth Sesqui is in other hands.

Pat,

Mitch Kachun is one of the leading, if not the leading, scholar on the commemoration and celebration of emancipation and abolition by African Americans in particular, and by the US as a whole.

In the book “Remixing the Civil War,” he has an essay titled “Celebrating Freedom: Juneteenth and the Emancipation Festival Tradition.” In it, he examines the history of Juneteenth, and acknowledges that this particular holiday has a lot of momentum behind it. However, Kachun himself opines that National Freedom Day (Feb 1) would make for a better day to commemorate the end of slavery. (I summarize his argument at the bottom of this piece.) If you can get the book from a local library, that essay would make for good reading. Of course, I say that as if you don’t already have dozens of things on your reading list.

I will repeat one point Kachun makes: Juneteenth is a very Texas-specific event, and even then, it is specific to a section of Texas. Freedom came to different people at different times in different places in different ways. The “story” of Juneteenth is one that takes away from the diversity of freedom narratives.

For example: in fact, there were black Union troops in Texas during the war, before Juneteenth. Some were probably former slaves who gained their freedom by enlisting. They were agents of their own liberation. The Juneteenth story does not account for these African American agents. It is about an isolated group of backs in the Trans-Mississippi region who learn about emancipation almost literally at the last minute from Union soldiers. Whilst black Union soldiers were fighting and dying to defeat the slaveholding regime within the state’s borders.

But yes, given the momentum behind it, it’s probably too late to put the Juneteenth horse back in the barn, in terms of it being “the” day for commemorating the end of slavery. But the use of that day has been contested. And note that, National Freedom Day came about due to the activism of a group of African Americans.

I would be more inclined to agree with that were it not for having seen, some years back, flyers posted around Minneapolis/St. Paul for a Juneteenth celebration there. While June 19 has a very specific, regional significance, any date chosen on the calendar will have a certain amount of arbitrariness.

I have been to Juneteenth celebrations in Hempstead, Brooklyn, Buffalo, and Westbury in New York. It is currently the most widely celebrated “Emancipation” holiday in my community and it has the advantage of having been spread and maintained by the African American community, often unknown to whites.

RE: “While June 19 has a very specific, regional significance, any date chosen on the calendar will have a certain amount of arbitrariness.”

That is correct. During the war era, different people became free at different times in different ways in different places. No one day is perfect for commemorating emancipation/abolition. So the question is, when you compare these different dates, which one comes closest to being “the best?”

Without question, Juneteenth is the most popular. Is it objectively “the best?” I’ve heard convincing arguments to the contrary.

But I don’t know if anyone is going to stop the bandwagon… we may see more places hop on it. Juneteenth kind of filled a void in a lot of places, it has had well-meaning people advocate for it, and now it has, as I keep saying, momentum.

I don’t think it will come to Washington, DC, though. The District of Columbia has established April 16 as “Emancipation Day.” It commemorates April 16, 1862, the date that slavery was abolished in the District. City government workers have the day off, although most businesses stay open.

“Without question, Juneteenth is the most popular. Is it objectively “the best?” I’ve heard convincing arguments to the contrary. ”

Hari Jones has made a very cogent argument against it.

RE: “Hari Jones has made a very cogent argument against it.”

Yes, he’s one of the folks I had in mind.

The US has established a day to commemorate the Congressional resolution for the 13th Amendment: National Freedom Day. It seems that very few people know about this day. I talk about that here.

Thank you for sharing this and providing insight into somthing I honestly was not aware of. I would suspect that perhaps it is not widely known is given that while the 13th Amendment constitutionally abolished slavery, equality proved to be an illusive reality. Even when this national day of observance was decreed in 1949, many African Americans would not consider themselves “free” in many parts of the country. Interesting to think of how Truman frames the discussion of the 13th Amendment, notions of “freedom,” alongside the United Nations in the wake of World War Two.

It’s not uncommon for politicians, intellectuals, writers, etc, to draw parallels between historical and current events. How often, for example, do we see someone examining some controversial issue based on their interpretation of the ideals and rhetoric of the Founding Fathers?

Following World War II, there was some concern that the Unites States’ history of slavery and segregation contradicted the notion that the US was the leader of the “free world.” National Freedom Day was a way to affirm that the US was, by or at the time, truly the land of the free. Or, it was an attempt to make that affirmation.

Agreed. I definitely believe the author downplayed the extent to which the abolitionist party had an impact in shaping Southern fears of the North over a several decades long period. Just because a party may be small in number does not mean that group does not hold enormous influence, especially over certain individuals and issues, both North and South. While abolition might have been pushed to the side per the necessity of military action and preservation of Union, it was their continuous action over several decades leading up to the Civil War that stoked the fire of secession, which cannot be overlooked nor considered a failure. Thank you for your thoughts!

Nice piece that challenges us to think about what the 13th Amendment meant in 1865 and today.

Curious if you have read the recent Disunion piece by the NYT about “Abolition” and its failure. I agree that the prolonging of the war into 1862 and military failures necessitated a broadening war policy that led to emancipation and the 13th Amendment. We definitely try to put the 13th Amendment into this “neat narrative package of American Exceptionalism.” Like the use of “Abolition,” today, we don’t understand its full contextual meaning in 1860 America. Likewise, the 13th Amendment is often viewed as this heroic symbol of progress. Nonetheless, as you nicely put, we must also understand and unpack the evolution of the 13th Amendment and the military, political and social environment from which it emerged. Great piece on this 150th anniversary. Thank you for sharing.

I thought it made some good points, but it was also incredibly sloppy in places. The author fails to consider the impact that the abolitionist community played both in the halls of Congress as early as the 1830s through the bitter debates of the 1850s. Their efforts certainly helped to shape how white Southerners viewed the North on the eve of Lincoln’s election. I also think we have an unfortunate tendency to think of the abolitionists as a monolithic movement. He referenced the Liberty Party, but that doesn’t exhaust the ways in which abolitionists themselves thought of one another.

Thanks for the kind words re: the post.

very nice, thoughtful, nuanced, contemporary.

i am a member of the thaddeus stevens society.

one helpful (i hope) quibble: may i respectfully suggest that the text state up front samuel cox’ ‘home state’ (ohio) as an assist to readers (like me!) save us a click.

I probably need to clarify a point from my original post. January 1, of course, is already a legal holiday, but I was referring to a holiday to specifically recognizing the end of the nefarious slave-trade and all its appalling evils. To that end, I think that January 1 is more deserving of recognition than January 31. More specifically, without the trans-Atlantic African slave trade there would have been, quite obviously, no African slavery in America. And another considerstion: when a proposed amendment reaches the States from Congress, it has no binding force at all. Absolutely none. In fact, the States may, if they choose, use the proposed amendment as toilet-paper. So again, December 6 is a better choice. Taken together, that may be why January 31, quite properly, is unappreciated and ignored by the vast majority of Americans.

Taken together, that may be why January 31, quite properly, is unappreciated and ignored by the vast majority of Americans.

I am not so concerned with a specific day of the year, but with the more general observation that this country does not make more of an effort to remember the end of slavery.

Emancipation Day (April 16) is a legal holiday in the District of Columbia. Wikipedia mentions that observances also take place in Florida, Mississippi and Texas. Maybe there will be a federal holiday someday.

BTW, did Congress make any observance of the 13th Amendment 150th?

Mr. Cheeseboro have you heard of the Corwin Amendment?

I don’t think any of us have ever heard of the Corwin Amendment. Please explain. What is this amendment that you speak of?

As for which holidays should or should not matter, I really just followed your lead from your discussion of Lee-Jackson Day, where you placed tremendous emphasis on the relative importance of Lee-Jackson Day in comparison with MLK Day. I therefore concluded, very reasonably I might add, that you would attach similar importance to the idea of Holidays celebrating, respectively, the end the slave-trade and the end of slavery in America.

If you are asking me personally than the answer is yes. I would say given the values that most Americans hold dear that commemorating the end of slavery would better reflect our collective belief in the expansion of freedom.

I think one possible reason there is not national recognition, in maybe the form of a legal holiday, is because as of January 31, slavery was still lawful and very much alive in the U. S. (Kentucky and Delaware were still slave states). It wasn’t until Georgia ratified on December 6 that slavery was finally made unconstitutional. So December 6 would probably be a better choice. And that, in turn, invites discussion as to why we do not celebrate either March 2 or January 1 as national holidays, as these dates, respectively, finally brought an end to U.S. involvement in the ghastly and unconscionable practice of slave-trafficking. Personally, I think both are equally deserving of recognition and celebration.

As for the final comments regarding your students, I am sure you treat the matter with the special sensitivity it requires. Still, the topic must make a unique impact on your African-American students. Have they also expressed the idea that they would like to see these dates recognized as a National Holiday?

I haven’t noticed any difference on this level among the African American students that I’ve taught in Boston vs. Charottesville. My students are deeply engaged in the history, but rarely do they concern themselves with what holidays should or should not matter.