For the past few days I’ve been reading about the expansion of slavery into the southwestern states during the 1830s and 40s. Silas Chandler was two years old when his master, Roy Chandler, moved from Virginia to Mississippi in 1839. This was right in the middle of a severe economic downturn owing to runaway speculation as well as dangerous banking policies (or lack thereof) on the state and federal levels. It all came temporarily crashing down and the Chandler family found itself right in the middle of it. Right now all I have are a lot of questions about the family’s history in Virginia, why they moved to Mississippi, and the challenges of getting settled at such an uncertain moment.

I am relying on a number of books to help fill in the big picture, including Ira Berlin’s, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves, Joshua Rothman’s Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson, Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism and Walther Johnson’s River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. From here I will look more closely at Palo Alto and the local region in which they lived.

For now I want to share a wonderful passage from Johnson’s River of Dark Dreams, which concludes a section that explores the pro-slavery writings of Chancellor Harper and Samuel Cartwright:

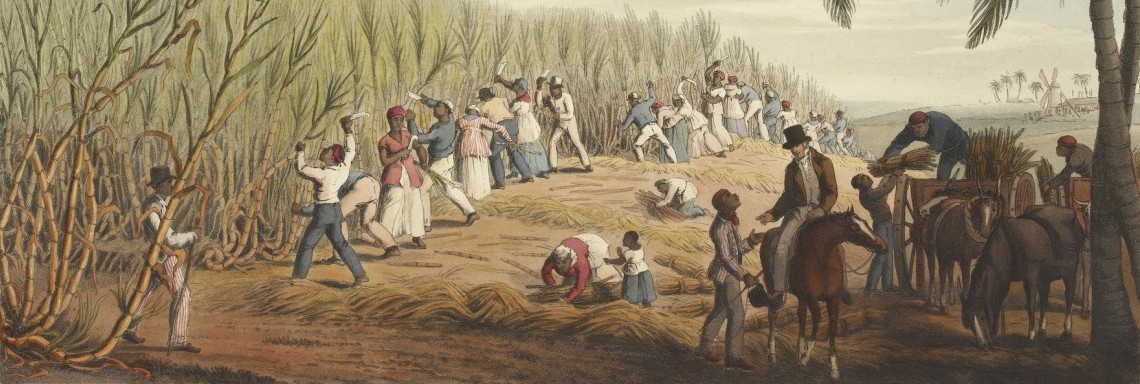

Historians have generally concluded that the writings of men like Harper “dehumanize” African-American slaves. This formulation has the virtue of signaling their repudiation of Harper’s views, and of reasserting a normative account of humanity as the standard of historical ethics: these are not the sort of things that human beings should be allowed to say about one another. yet a troubling problem remains. Harper, Cartwright, and indeed countless other slaveholders and racists in the history of the world were fully able to do what they did and say what they said, even as they believed and argued that their victims were human. Imagining that perpetrators must “dehumanize” their victims in order to justify their actions, inserting a normative version of “humanity” into a conversation about the justification of historical violence, let’s them–and us–of the hook. History suggests again and again that this is how human beings treat one another. Even as he continually referred to domestic animals in his essay on slavery, Harper always did so by analogy. He did not say blacks were animals; he said they were like animals. Indeed, he was quite clear in affirming his belief that slaves were “human beings,” members of a “cognate race.” There was a religious reason for his malign precision: to argue otherwise would be to question the biblical account of the origins of mankind in the coupling of one man and one woman in the Garden of Eden. But there is little evidence to suggest that Harper and his class felt any conscious or unconscious need to change their behavior in light of any concern for their common humanity with their slaves. Indeed, it seems quite clear that no small measure of the reliance they placed on their laboring slaves–to nurse their own children, bring in the cows, sow the cotton, select the seeds, weigh the bales, cook the meals–signaled their reliance upon the slaves’ “humanity.” Likewise the satisfaction that they got from violence–threatening, separating, torturing, degrading, raping–depended on the fact that their victims were human beings capable of registering slaveholding power in their pain, terror, grief, submission, and even resistance.

A better way to think about slavery might be as a concerted effort to dishumanize enslaved people. Slaveholders were fully cognizant of slaves’ humanity–indeed, they were completely dependent upon it. But they continually attempted to conscript–simplify, channel, limit, and control–the forms that humanity could take in slavery. The racial ideology of Harper and Cartwright was the intellectual conjugation of the daily practice of the plantations they were defending: human beings, animals, and plants forcibly reduced to limited aspects of themselves, and then deployed in concert to further slaveholding dominion. In the 1830s, this plantation-based version of human history transformed the Mississippi Valley into the Cotton Kingdom. By the 1850s, it was ready to go global. (pp. 207-08)

I am still digesting all of this, but I would love to hear what you think.

I have such a visceral reaction to the concept of slavery that it is hard to speak calmly and rationally of the reasons and how “necessity” makes good people do bad things.

From the beginning of time, the strong preyed upon the weak and controlled the behavior, work and even survival of others “below” them. But slavery was unique in that it was not just the economic control or hierarchy of centuries, it was the physical ownership of human beings and whether treated badly or with humanity, it is beyond heinous to imagine. The notion of having less control is still real to every poor or low wage worker in the world, but the idea that every waking moment and activity can be controlled by someone with life or death power over you is beyond our ken even though it is still real for some people.

I have real difficulty reconciling good men doing heinous things. I have even more difficulty with those men being honored and memorialized. I guess my heart only bleeds one way.

I have real difficulty reconciling good men doing heinous things.

The challenge is to understand actions and decisions in the context in which they were made, however difficult that may be to do. I highly recommend Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s book, Reading the Man. You will find it very interesting.

This seems to be coming to one of the the non-economic motivations for wanting to maintain slavery. If a man owned human beings, did that make him feel sort of super-human?

Jeff Davis, trying to puff up some great eternal principle from secession, said it was the tension between the central power and the local powers(crudely put). While he was avoiding this conclusion, the fear was the central power interfering with the local exercise of unrestrained power over other people. The maintenance of a hierarchical society in other words.

Lincoln, in his understanding of conflict sort of agrees, saying it was an eternal contest between the divine right of kings and “all men are created equal.”

Johnson is saying Davis didn’t need to dehumanize anyone to practice slavery.

Dehumanizing is something out of the 20th century. Bureaucratic, rational(in the economic terms). with considerable distancing. Slavery was personal, upclose. Johnson argues that the meaning of slavery was to dominate other people.

Hmm. I had a response which seems to have headed into the great bit bucket in the…

To reiterate what I think I said… Yes, ownership differentiates that category of “human capital”. I also suspect I am too much interested in what I view as the process and contiuum of categorization for “dishumanizing” (a term I appreciate you pointing to). Not sure if there is a bottom or solid stance to such interests.

Regardless, truly appreciate your blog.

Hi Karen,

Thanks for the follow-up. I certainly understand the point you are trying to make and I think it’s a good one.

Yes, well, owning does differentiate that category of “human capital.”

I am probably too simplistically interested in what categories allow for the process and continuum of dishumanizing (good term and thank you for pointing it out).

Might it be fruitful to consider enslaved as a category of “dishumanizing” along a continuum of types of work humans do?

For that process, the concept of “human capital” (one I don’t like much personally) might explain how we can easily dismiss the “dishumanizing” of the people who work at this moment to create our iPhones for example, as well as historically those enslaved.

Human capital is the “bundle” of skills, knowledge, habits, personality traits that a person “possesses” so as to “fit” specific occupations that produce things of value.

But don’t we miss something salient if we overlook the key difference of ownership of one’s body? Thanks for the comment.

Johnson is very good on this. In most places and most times, many groups of people were considered people, but lesser sorts, to be commanded and controlled. American slavery was one, extreme version of this.

The conclusion of “River of Dark Dreams” where he brings this thinking into our own time, has tremendous force.