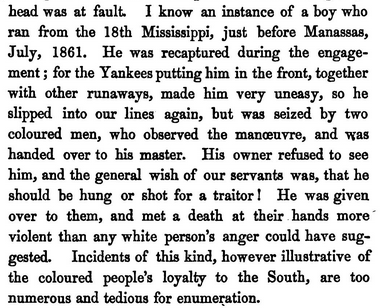

This is one of the most unusual accounts that I have ever come across about Confederate camp slaves. It is also one that I am struggling with how – if at all – to utilize. The account comes from Battle-Fields of the South: From Bull Run to Fredericksburg. This 2-volume work was published between 1863 and 1864 and written by an “English Combatant.” The writer supposedly served in a Mississippi regiment and saw action in Virginia. His account is supplemented with accounts from other soldiers.

This particular account reportedly took place before First Manassas.

It is certainly a hair raising scene, but is there any truth to it? I should first point out that this account is cited in numerous studies from Bell Wiley’s Southern Negroes to Ervin Jordan’s Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia. Other passages can be found in books about the battle.

In a recent blog post, Al Mackey questioned the overall value of the book. It’s worth reading and he definitely deserves some kind of medal for making it through both volumes. Al’s close reading of the text leaves little doubt that one should approach it with a good deal of caution and skepticism.

This certainly captures my initial response to the excerpt above. I have never heard of Union soldiers placing escaped slaves in harm’s way as described by the author. My first move was to look for any corroborating evidence, but I came up empty. A fellow historian and expert on the battle and the relevant primary sources confirmed my suspicions.

That takes care of the Union side, but what about the description of the execution of a camp slave at the hands of his fellow slaves? I am unaware of any corroborating evidence among Confederate sources related to the battle. The scene is framed as a common expression of “loyalty to the South,” but it can’t be dismissed for that reason alone.

With all of that said, I am still left with the following question: Of all the ways to describe slave loyalty, why sketch out such a violent scene that pits slave against slave? Assuming that it is a fictitious scene, how did the author even come to imagine it?

I have read a number of other accounts that suggest that camp slaves organized themselves around an unofficial hierarchy and that certain communal bonds developed during the war. Is it possible that these men viewed this escaped camp slave as a betrayal that deserved punishment?

Even with all of the problems in this account I am still not ready to toss it aside. Any thoughts?

x[Kevin — feel free to delete if the suggestion is too goofy to contribute to the conversation.]

x

Maybe you could divide the assessment of this passage into two parts? Write up the passage in a short separate article for publication, in which you fully review the open credibility and contextual issues (including the interesting suggestion by Jimmy Dick for placing it in the context of other English political writing at the time), even if you need to leave most those issues tentatively answered or unresolved.

Then you can give the matter a cursory treatment in your book, perhaps just a line in a footnote, with a cross reference to the separate article. That way your full justification for the treatment in your book is publicly available without bogging down the narrative of your book.

As you probably know, I’m not a historian or an academic of any stripe, so I have no idea whether this would be considered practical or even cricket. It would certainly mean extra work, which might alone be sufficient to disqualify the suggestion.

It doesn’t surprise me that there were those who might have wished to see such an account published in London, given the timing. I think we might need to look more into this mysterious “English Combatant,” T.E.C. There are several online sources that identify the author as Thomas E. Caffey (Co. E, 18th Mississippi), though none, so far as I can tell, which provide proof of this. If you look at online issues of the Memphis Daily Appeal from 1862-1863, there is a correspondent who shows up quite frequently, one “T.E.C.”. His reports seem to indicate that his travels mirror those of our “English Combatant” (even often mentioning the 18th). His accounts include one description of a cheery Christmas army camp scene where “negroes are busy and gaseous over a pyramid of pots and pans.”

In “The Moving Appeal: Mr. McClanahan, Mrs. Dill, and the Civil War’s Great Newspaper Run,” Barbara Ellis identifies the correspondent: “‘…(Thomas E. Coffey) provided human-interest about the raw ‘federalists’ arriving in their ‘pretty uniforms’…who then burned, raped and ravaged nearby Centreville, and then sacked churches and used their floor as latrines…[Appeal publisher] McLanahan put blood on the breakfast table…” (p. 122).

Caffey/Coffey. I suspect that Confederate Officer T.E.C’s account may be agenda-driven. Was McLanahan heavily involved in the Confederate effort to win British support? He was the editor and publisher of a “refugee” paper in the South. It would make sense to me.

Edit: 1861-62 issues of Daily Appeal.

This book looks an awful lot like a piece of propaganda written in Great Britain as a tool to influence the way people thought about the Confederacy. All the hallmarks are there of an author with a lot of information available to them via Union sources and not so much from the Confederacy. Everything that would make the Confederacy look good is there and everything that makes the Union look bad is there.

The lack of specific names for the many incidents really stands out. The whole thing feels like someone who could give details of uniforms and things like that in the first two years of the war fed that information to someone else who then filled in the missing parts and added the descriptive prose meant to alter the perceptions of people.

It seems a bit dozy on the part of the historian profession if the origin of this book has never been investigated. Is it too late to find out who wrote it? Was it created by the confederate propaganda machine in the UK?

There is no doubt that AJL Fremantle wrote his own book and saw what he said he saw (albeit with his biassed interpretation), but why would “English Combattant” want or need to keep his identity secret after reurning to England?

I’m having trouble with the phrase, “I know of an instance.” I don’t know why the author wouldn’t say “I saw” or “I witnessed.” It might just be just style. Nineteenth-century prose tends to drown a point in a pond of words.

But it sounds like the author is saying, “I heard this from someone.” It reminds me of how urban legends always start out, “This happened to the friend of a friend of mine.” A battlefield legend? I could see this being a popular story around campfires in the rebel army; it hits so many popular themes:

Our slaves love us.

Our slaves are cowardly.

Our slaves are brutal.

The Yankees treat our slaves worse than we do.

There’s enough detail–“18th Mississippi”, “just before Manassas, July, 1861”–to give the story some verisimilitude, but nothing specific enough (like names) to make it easily verifiable. I wonder if the same story pops up elsewhere, but with different details. Maybe even in a different war.

Excellent point. I’m quite suspicious that there are no names in the story: of the escapee, the master or the other camp slaves.

As a comparison, I note that Mary Chesnut’s diary contains lots of rumors, often very circumstantial accounts, with footnotes from C Vann Woodward exploding them.

I would think the account should be mentioned, with necessary caveats.

I agree. Kevin did say that the source he’s pulling from has some veracity. So it’s not the source as much as the story.

With only one source and no verification, I feel like this could derail your narrative. It seems more like something for an appendix, or a passing mention in the endnotes. There might not be enough documentation to place it in the main body of the book and maintain credibility.

But be sure to acknowledge it SOMEWHERE, even if it’s just online. You don’t want this being dredged out as an example of “the TRUTH that Kevin’s trying to cover up.”

But don’t derail your narrative for it. This seems too gossipy, like a tabloid story. I fear it would stop the chapter’s flow dead in its tracks.

There are other reasons for the enslaved camp workers to want the runaway dead. Perhaps he stole from them first? Or they were punished because of his escape?

With no other corroboration I would, as suggested elsewhere, mention it but point out the problems with the story. An added point to consider, would be the hope of the “English” writer to convince European readers of the CSA cause.

I tend to think accounts like this speak to the fears of the moment rather than realities of the time. First Manassas–the first major battle of the war–features a number of claims related to black Confederates, most of them made from a distance and uncorroborated by anyone who was there.. Take, for example, the oft-repeated assertion that fully 10% of the Confederate army at Manassas was comprised of African-American men. It’s a ridiculous claim, but almost certainly reflects Union fears at the time that the Confederates MIGHT use slaves as soldiers. It’s worth noting that over time these sorts of claims largely vanished from narratives of Civil War battles. I suspect their disappearance reflects the waning fear that such a thing would happen (because, repeatedly, it did not).

In this case, the story of escaped slaves being placed in front of Union lines as human shields serves the dual purpose of condemning the disloyalty of slaves and painting Yankee enemies as brutish and inhuman. I am struck by the parallel between this account and the widely told tale that emerged after First Manassas that the US troops intended to handcuff Confederate prisoners, line them up, and use them as shields during the Union army’s next advance on Richmond. Stories like that lived a brief, vivid life until reality demonstrated that such things had not and would not be happening.

This story from the English Combatant seems to fit into the same category.

What is amusing about the 10% claim is that it means one of two things, if true. 1) The Confederate army was larger by 10% than records claim as the perfidious Yankees scrubbed the records after the war, or, 2) There were several thousands of southern white men who were happy to have a black man fight his war for him. So either the history of the war needs to be completely re-written to accurately portray larger Confederate armies than has been thought, or the manly courage of the southern white man wasn’t all that manly as tens of thousands of Black men did the actual fighting!

Also, one for Kevin. I’m guessing passes were needed for many servants to move through Confederate camps? This and/or a gray coat was the signal that an enslaved man ‘belonged’ there and was not a spy.

There’s also a possibility that, IF it occurred (and that’s a very big if), it also could have occurred out of fear and anger. The dark underside of the oft-stated slavery defenders’ insistance on how much slaves loved their owners was the constant, obsessive fear of servile insurrection. It was that fear that openly appears in the Confederate reaction to the announcement of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. I’ve mentioned Grimsted’s “American Mobbing” before. Even during the antebellum period, when the white powers that be suspected that a slave revolt was in the works, they would begin “investigating” it, which often involved interrogation techniques used on slaves that we’d consider to be torture. It’s possible (although I am still highly skeptical) that the remaining camp slaves would be willing to do the dirty work both out of anger against the runaway for jeopardizing all of them and to prove their loyalty to those who had the power of life and death over them and their friends and families back home.

Obviously, like you, I’d be extremely reluctant to put much weight on the story without something to corroborate at least a part of it. If I’d use it, I’d use it with caveats prominently around it.

“It’s possible (although I am still highly skeptical) that the remaining camp slaves would be willing to do the dirty work both out of anger against the runaway for jeopardizing all of them and to prove their loyalty to those who had the power of life and death over them and their friends and families back home.”

If this incident happened as described, the other camp servants’ motivation to show their own loyalty to their masters should not be discounted. They would easily have seen the teenager’s running away as an act that endangered them all.

It seems plausible to me. I’ve seen kids tattle on each other to teachers they hate because it helps them stay in good favor with the authorities. So it’s a little bit plausible that slaves might do the same.

The attempt by 77 slaves to escape DC in 1848 on the Pearl was betrayed by another slave.

My two cents: include it in an explanatory endnote or write about it at length (like an extended blog post) in an appendix. In either way the account does not send your chapter down a rabbit hole.

At that point in time, there was no provision for using black men as troops, so I am very dubious of that aspect of the story. I suspect what really happened is that the man ran away, then in the rout after the battle was captured by the Confederates. As for the execution, I can see it happening, but I can also see this as embellishment.

My first thought was to ask when this account was published, figuring it was part of the post-war reminiscences that sprung up a generation or so after the war. So I was really surprised to see the 1863-4 date. The former would hurt its veracity considerably, the latter does add some complexity.

You’ve given a lot of reason why the source is problematic. What I cannot figure out is why this account, and why at that moment? Again, writing post-war this kind of makes sense–there’s an apologetic quality for the Lost Cause to many of those accounts. But written mid-war, when slavery’s primacy to the War’s cause wasn’t in question, gives me pause.

That it’s an isolated account, one that’s not corroborated by other sources, only adds to the mystery.

Were I confronted with the source, I would feel obligated to include it in my work, and perhaps put it in the context of other examples of Stockholm Syndrome (sort of like the Capos in concentration camps). You obviously can’t ignore it, and though you have much to refute it, staying true to the historical discipline and process, I might say somehting like “we just don’t know, but it could be true” (though not quite as easily as it could be false, for the reasons you stated above).

What an odd account though….

Some of his other accounts are incredibly reliable. He offers a very colorful account of camp slaves outfitting themselves with the uniforms from dead Union soldiers, which is corroborated by a number of other writers.

I may try to thread the needle with this one, but it’s definitely a tough call.

You’re clearly in writing mode right now as “thread the needle” is pretty much what I said in about 10x as many words. (I’m in page proofs with one project and notetaking on my dissertation.)

Does it matter when this was written? Proslavery propaganda existed before the Civil War. I read loyal slave narratives in 1855.