Earlier today I came across this wonderful postcard featuring the Jefferson Davis monument on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. This street view captures a great deal of detail, but it also serves as a reminder of the extent to which the monuments themselves shaped the surrounding physical landscape as well as the memory of the war.

This scene likely takes place in 1907 during the annual meeting of the United Confederate Veterans and the dedication of the Davis and J.E.B. Stuart monuments. The Robert E. Lee monument had been dedicated in 1890.

The four veterans depicted here may have walked from the Old Soldier’s Home, located nearby or perhaps they were in town for the annual UCV meeting. [There is likely additional information on the reverse side of the postcard.]

The scene clearly illustrates the early development of the Fan District, which eventually featured large estates sold exclusively to white families. The wide tree-lined avenues that included a large grassy median were hallmarks of the “city-beautiful” movement that guided the expansion of cities at the turn of the twentieth century.

Situated in the foreground, the veterans offer a sharp contrast with the street as it stretches into the distance and a future filled with possibility. It suggests that Richmond’s expansion and modernization would not take place by leaving the past behind. Quite the opposite. The monuments served as a reminder of the “brave” veterans now in their twilight years.

There is a tension, however, between the present and past in this image. Richmond’s future literally cuts through the old earthworks that once ringed the city, which served as protection for Confederates from the “Yankee” army. The soldiers—a living reminder of the past—huddle close to a physical reminder of their service that will also soon be completely erased from the landscape, leaving the monuments behind to do the work of remembrance and commemoration.

Defenders of Confederate monuments often argue that their removal is tantamount to erasing history, but here we see an example of how the monuments themselves, along with the development of a new neighborhood, contributed to the destruction of the physical landscape and history—specifically the history of who constructed these earthworks.

From the beginning of the war until its close the Confederacy mobilized thousands of enslaved Black men for a wide range of military projects, including the construction of earthworks. Though it was not always popular policy, it was carried out as a matter of necessity. The utilization of enslaved men helped to maximize the number of white men that could shoulder a rifle and help to offset the North’s advantage in manpower.

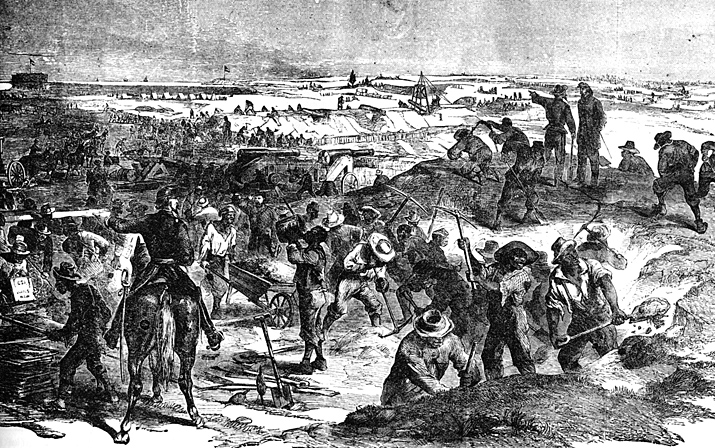

[Impressed slaves building fortifications at James Island, South Carolina. (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.)

The history of these men was lost with the destruction of the earthworks and the construction of Monument Avenue. The scores of Confederate slaves that labored on Richmond’s earthworks evolved into tales of “loyal slaves” after the war—a narrative that was reinforced and encouraged by the monuments themselves.

It’s a reminder that history and memory are always in constant tension with one another.

The Confederate monuments along Monument Avenue have all been removed, along with a Civil War cannon marker, located on the grassy median and roughly on the site where the earthworks once stood.

Cannon marker on Monument Avenue (Photo shared by Christopher Graham.)

What Richmond has lost with their removal means different things to different people. But with removal comes the possibility of reshaping these public spaces and reconnecting to the past in ways that bring more people together and that reflect their shared values.

Our historic and commemorative landscapes are always evolving to meet the needs of the community. We are constantly renegotiating our relationship to the past, including the stories we tell to help us make sense of who we are, where we come from, and where we are going.

“ history and memory are always in constant tension”

Well said.

And Arthur Ashe is the last man standing on Monument Ave. Amazing.

What a fabulous post card — showing the cut-away of the famed “Dimmock Line” on the left-hand side! Guess who was erasing history then?

Like you, I wish that we could read the back of the card. It could be very interesting!

Hi Noma,

Still searching.