Of all the efforts on the part of state legislatures to regulate the teaching of history, the most baffling is the attempt to ensure that our students do not experience feelings of discomfort. It assumes that teachers have the power to manipulate the emotions of their students. More to the point, it raises the question of what, if anything, is wrong with such an emotional response when studying history.

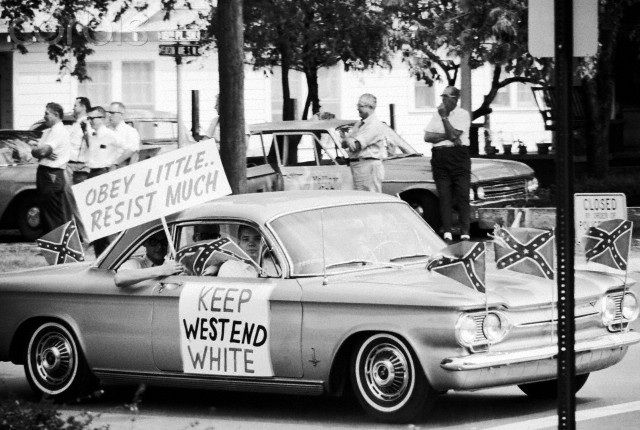

September 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, USA — Teenagers wave signs and confederate flags from their car during the fight over desegregating Birmingham’s public schools. — Image by © Flip Schulke/CORBIS

In fact, I would suggest that a good history class should bring out a wide range of emotional responses in our students.

This has been driven home for me time and time again in the classroom and on class trips to historic sites across the country. My experience working with students at a Jewish Day School, in particular, is worth spending some time exploring.

For four straight years I co-led a civil rights-themed tour that in different iterations included stops in Atlanta, Tuskegee, Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham, Jackson, and Memphis. It’s an intense 5-days that, in addition to stops at key historic sites, includes interviews with individuals who participated in the Freedom Rides, the march from Selma to Montgomery, and lawyers who worked to bring legalized segregation to an end.

We also spend a good deal of time at the end of each day reflecting on the significance or meaning of this history for us as Jews.

This last point takes center stage when visiting Montgomery. One of the challenges we face organizing this trip is ensuring that students have access to Kosher food. Thankfully, there is a very welcoming synagogue in Montgomery that is more than happy to host and provide us with a hot meal. We follow up the meal with a meeting with the rabbi.

Keeping with the theme of our trip, the focus of this session is the role of Jewish residents of the city during the civil rights movement. I think our students expect to hear how the Jewish community rallied alongside Montgomery’s Black community to help achieve the goal of civil rights. They are quickly dispelled of this assumption.

They learn that Montgomery’s Jewish community were, in many ways, part of the broader Jim Crow culture of the time. Jews accepted the racial order of the mid-twentieth century. They lived in white neighborhoods and their ownership of local businesses resulted in placing a high value on maintaining peace within the city limits. No doubt, some supported the efforts of civil rights activists, others may have been sympathetic, but failed to act, and others resisted altogether.

I think for some of our students, the challenge and even shock is in acknowledging that an embrace of the Jewish faith did not preclude defending a culture and political system built on white supremacy. Some students pushed back and suggested that Montgomery’s Jews had abandoned their faith rather than appreciating the extent to which religious identification and practice influence and are influenced by the broader cultures in which we live.

Conversations about this particular issue continued for the rest of the trip and even after we returned home. In these uncomfortable moments the distance between past and present shrinks. In these moments we sometimes catch ourselves reflected in the past. Students are forced to acknowledge the likelihood that they would have behaved in a similar manner, in that particular place and at that particular time.

Studying history can and should do that. It can force us to step outside of ourselves, to look at the world through the eyes of other people who came before us, to whatever extent the historical record permits. What conclusions and connections students make in these moments depends on a wide range of factors, but it often brings out a wide range of emotions, including feelings of discomfort. I have often experienced this in my own reading and research and I’ve learned a great deal as a result.

I welcome these moments and I encourage my students to keep an open heart and mind when confronting the past. It has the potential to make us all better people.

Insightful piece. It’s hard when we realize that our heroes (and ourselves as well) have feet of clay.

I well remember how horrified I was when my dad told that Earl Warren, who was Chief Justice at the time, had been a prime mover behind the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII. Warren later recanted his support in a somewhat self-justifying way in his autobiography, which was published posthumously. But the man who pushed so hard for unanimity in the Brown v. Board of Education decision never apologized or acknowledged his error for the internment. Yes, we humans are a complicated species.

Does history teaching in schools lead pupils to expect historical actors to be all-round heroes or villains? Or is making moral judgements on such figures part of what they’re expected to learn? Surely the role of major figures can be evaluated in the context of each of the main events they were involved in. Here in Britain for example we need to be able to accept that Churchill both played a crucial and unique role in the defeat of the Nazis in Europe, and was a racist mass-murderer in his policies towards India. Historical figures should surely be evaluated by the effects they had, rather than second-guessing the destinations of their souls, if one happens to believe in that sort of thing.

“Or is making moral judgements on such figures part of what they’re expected to learn?”

I would hope all people learn to make moral judgments. It’s not really something schools should teach though. I’m more worried about the the alternative: people refusing to make moral judgments – about anyone but instead offering a lot of wishy washy “yeah, but he/she isn’t all bad…” That’s the road to toxic relationships.

At the same time, making a moral judgement about a person, past or present, shouldn’t you from preclude you from acknowledging the person’s strengths and weaknesses. One can conclude Lincoln was good and Davis was bad yet acknowledge Lincoln’s views or race or Davis’ sincere convictions and worth ethic.

I think one of the hardest things for people living now to deal with is realizing that historical figures who seem likable can support things that we find loathsome. One of those for me is Porter Alexander, a Confederate artillery commander. His memoirs are a delight up until a point that really threw me for a loop. In 1863, his wife had twins their 2d and 3d children. In his informal memoirs, he calmly notes, that recognizing his wife’s need for more help, he BOUGHT his wife a nursemaid.

Hi Margaret,

I completely agree. It’s enough of a challenge just trying to understand people from the past. Of course, we should always remember that, like us, people from the past were just as complex and full of contradictions.

I recall my eighth graders, “ But, Mrs. Crockett!!!” over some unexpected turn in history. Very telling that, in the current, shameful battles over the teaching of our history, legislators assume students will associate themselves with slaveholders rather than abolitionists, and rebels rather than US soldiers. Thank you for teaching your students and us readers – keep on keepin’ on!!

Good points. Reading this I was thinking about how to balance the idea that although narrow slices of history can really shape our worlds, history itself does not fully define us as individuals. I’ve also wondered whether the better a person grasps the fact that people just like them are now viewed as villians in history, the more likely they are to resist falling into that kind of moral complacency in the future. Great read.

Hi Gideon,

Thanks so much for the comment. You said:

I certainly hope so.