I‘ve been following this story out of Tennessee [and here] involving a local chapter of the UDC and SCV and their plans to honor 18 so-called black Confederates. I was actually contacted by the author of this article for my position on this issue, which you can read. The author does a pretty good job of presenting the various perspectives. There is always the danger that the reporter will take something out of context or simply fail to follow a line of argument. In this case the author, Skyler Swisher, does a pretty good job. The only thing I take issue with is having my view juxtaposed against Wood’s as two competing interpretations. Simply put, Wood and the UDC are doing poor history. There is really no interpretation to take issue with since it is fraught with basic factual and interpretive mistakes.

I‘ve been following this story out of Tennessee [and here] involving a local chapter of the UDC and SCV and their plans to honor 18 so-called black Confederates. I was actually contacted by the author of this article for my position on this issue, which you can read. The author does a pretty good job of presenting the various perspectives. There is always the danger that the reporter will take something out of context or simply fail to follow a line of argument. In this case the author, Skyler Swisher, does a pretty good job. The only thing I take issue with is having my view juxtaposed against Wood’s as two competing interpretations. Simply put, Wood and the UDC are doing poor history. There is really no interpretation to take issue with since it is fraught with basic factual and interpretive mistakes.

I would also like to clarify that I’ve never denied that the master-slave relationship could lead to mutual bonds of affection, though the nature of the relationship demands that we tread carefully. That’s not the issue here. My concern in these cases is that the SCV and UDC have gone to great lengths to honor these men for a role that they could never fulfill as slaves. Almost all the cases of black Confederates turn out to be slaves following masters. This necessarily implies coercion and ought to prevent us from describing their presence with the Confederate army as one of “service”. What is it about the concept of slavery that certain people cannot grasp? They did not serve nor were they soldiers and to imply that they were is to misread the historical record. There is a reason why the VA denied markers for these black men.

“Almost all the cases of black Confederates turn out to be slaves following masters. This necessarily implies coercion and ought to prevent us from describing their presence with the Confederate army as one of “service.”

Nonsense. I grant the number of Negro Confederate Soldiers was small, 3000-10,000 according to a Harvard professor, as many as 15,000 by other sources but, to suggest that all or even most who did fight were coerced to it is entirely unrealistic. First off, remember, not all slave owners were white! Black slave owners would have every bit as much at stake in the system (that I openly agree is morally wrong) as any white or Native American slave owner would have. There are just too many instances of Blacks in situations putting them easily in reach of freedom that they did not take. For example, a Confederate Negro at Gettysburg brought in 2 Union prisoners their Confederate guards got too drunk to keep. Why did he not flee with the Yanks? Also at Gettysburg, “reported among the rebel prisoners were seven blacks in Confederate uniforms fully armed as soldiers. Why were those Negroes standing with Confederate POWs? Why hadn’t they begged off claiming freedom? Even if loyal to the Confederacy, it would have been easy to get off that way. At Camp Morton Ill US POW camp for Confederates, 24 Negros died. Why were they there. Coerced? All they had to do, as could any Confederate POW, was to take the oath and walk out the door admittedly in Union service but not in battle again as a rule. Another Prisoner, when asked to take the oath of Loyalty was said to reply, “Sir, you want me to desert, and I ain’t no deserter. Down South, deserters disgrace their families and I am never going to do that.”

If these people were forced into their service, why did they join Confederate veterans organizations and more to the point, why were they welcomed int these organizations if they had to have been forced into their service despised by those around them.

“If Wood and the UDC want to honor the memory and lives of these men, then they should put up markers clearly stating that they were slaves, period.” As at the beginning of this, I say, nonsense! The instances of historical record are too many to dismiss. To ignore or dismiss their service as ignorant or coerced is simply pandering to a racist element within the population that simply do not want to hear a truth they do not like. It is also unjust to men who fought by their own choice. They may have been brought to it as slaves, and by all means, not all were, but once there, a decision whether or not to stay and fight was theirs. The possibilities and freedom of movement granted Negros with the army gave many in an enviable position to run.

Ironically, perhaps the first monument depicting a Negro soldier is the Confederate monument at Arlington erected in 1914.

Enough. I think I’ve stated my point sufficiently.

I grant the number of Negro Confederate Soldiers was small, 3000-10,000 according to a Harvard professor, as many as 15,000 by other sources but, to suggest that all or even most who did fight were coerced to it is entirely unrealistic.

No one has yet to do a serious statistical study, including Harvard’s John Stauffer. Stauffer pulled his number out of thin air, which he pretty much admitted to me in person.

You ask a number of questions, but your failure to arrive at an answer does not necessarily lead to your preferred conclusion. That is why we do research.

Ironically, perhaps the first monument depicting a Negro soldier is the Confederate monument at Arlington erected in 1914.

That is not a black Confederate soldier depicted on this monument: http://deadconfederates.com/?s=1914+moses+ezekiel This is a perfect example of what happens when one makes a claim without doing any serious research.

You’re speculating on the motives of those men, without offering anything as actual evidence of it. One doesn’t have to look at the PoW very closely to recognize that, North and South, they were a muddled mess. We’ve discussed elsewhere, for example, how several African Americans swept up with Confederate prisoners were stuck inside the walls of Camp Douglas in Chicago for months before the War Department figured out their status and cut them loose. We’ve also seen a case where a very light-skinned slave intentionally “passed” as white and falsely claimed to be a soldier:

To be sure, this was written after Hannibal Alexander’s death, and reflects white veterans’ view of the man and his motives. We don’t know what Hannibal Alexander would have thought of this explanation. But even so, there’s nothing here that suggests any particular loyalty to the Confederacy, or to its cause or defense; it’s all framed as personal loyalty to his master and his comrades. Real Confederates chose to see the actions of men like Hannibal Alexander as those of a “faithful slave,” not those of a soldier willingly fighting to defend home and hearth.

Speculation about peoples’ motives, without specific evidence to suggest it, isn’t of a whole lot of use to historians. But just for grins, I’ll throw another one out that I’ve never seen considered by the advocates of black Confederate soldiers: they may well have seen imprisonment as the quickest route home. Well into 1864, prisoners on both sides had good reason to expect that their incarceration would be of relatively short duration, and within a few months they would be duly paroled and exchanged. That’s the way it generally worked for the first three years of the war. It’s entirely reasonable to believe that some men viewed remaining inside the pen as a difficult but temporary situation, one that would result in their being returned South in due course. Contrast that with the great unknown of being pushed out (literally) onto the streets of an unfamiliar Northern city, with no money, no friends, no contacts, barred from returning to the Confederacy for the duration, little prospect of being reunited with one’s family anything soon, and no clear future, and it should not surprise that some would choose to remain in a hard, but presumably temporary, situation.

Finally, you offer this quote:

I’ve seen that quote splashed all over BCS websites, but never sourced. Can you give me an original citation for that, please?

the definition of Confederate has changed , now anybody living in the CSA is a “confederate” even those who fought for the Union.

there is no problem that can’t be solved by moving the goalposts and rewriting the dictionary definition.

Still with the “black confederate soldiers”, huh? When revisionists like Stacey produce one, just one, official enlistment form or official government separation paper(s) of a black confederate who served as an authentic confederate soldier….. then I’ll take another look. Until such evidence is presented, this whole “black confederate soldier” thing is a crutch for certain southerners to lean on when trying to explain away the institution of slavery, and how it actually did cause that war.

All veterans hang unto their papers, as they open many doors after service is completed, and serve as actual proof of serving one’s country. I must have signed hundreds of official forms during my time in service, of which I still have many copies on file. No vet would not have such papers.

So, Stacey….. produce some.

I have read you blog and find it interesting. It seems some people are basing their argument on other people’s research and opinions. My grandfather was 5 years old at the beginning of the Civil War. His playmate was a slave boy about his own age. In 1920, they met, embraced, and reminisced about their past. Yes, you are right; there was a ‘bond” of which we know little about today. We frequently judge historical events by today’s standards.

“Black Slave Owners (Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860)” by Larry Koger is an interesting and well documented book which may improve someone’s understanding of what some people thought about the subject of slavery during that time period. Although I have no documented facts and figures to submit, I can assure you that a war as large and complex as the US Civil War will include people who fought for any reason including an African American fighting for the Confederacy. (I would expect them to be the exception rather than the rule.)

Al,

Thanks for the kind words re: the blog.

Please understand that I’ve never once denied that no blacks served in the Confederate army. I’m not even so concerned with numbers, though I assume for the obvious reasons that the number is very small given the lack of evidence. The Koger book is supposed to be worth reading, though I have not yet had the time to go through it. Thanks for the comment.

You are absolutely right and as you might suspect it is impossible to engage someone who approaches the study of history from this angle. Information is presented without any understanding of source or analysis. Even a cursory glance at this blog would demonstrate that these arguments have been presented over and leads to the same dead end.

What are you on? Stop smoking and do your research, there were Black Units and Native American Units in the South. The real history of these units were forbidden to be tauight when Reconstruction started. Southern history was not allowed to continue and the North destroyed records, books and no one was allowed to teach anything except what the Government instructed them to.

There are some historical books still around that describe in detail about the reasons that blacks fought for the South. Many did follow there “master”, but others fought because they were afraid of being moved to another country and seperated from their families. As a fact!!! The Great Emancipator had plans to ship all blacks to Panama when he found oil there, but when the wells were found to be shallow he changed his mind. His plan was to have the Blacks work the oil wells, have Fredrick Douglas be their President and sell the oil to America at cheap prices. And at the time of his death, he had written a plan to send all of the “free” blacks to what is now Cuba.Fredrick Douglas had already signed the document but “Abe” had not gotten to it.

The black people in the Southern states understood that the “freedom” from slavery did not apply to them because the only freedom was promised to the Northern blacks, the South had it's own President.

Blacks fought because that wanted to remain in America, but if you believe there were no black Confederates then the true history dies just as the North wanted.

“What concept of slavery can't we grasp”, that would be the concept that the North wanted to free the slaves. Right, they wanted to be free of them, and if you are one of those people that believe the WAR was all about slavery then you are a person that does not want to know the true history.

“HISTORICAL RECORD?” All attempts were made to destroy the true historical records in an attempt to make the North look right and to hide the true fact of their plan and the bottom line of the cause of the war. In part the war was started due to slavery, but not in the way you think. It was to remove the balck people out of the Unkted States and to hide the true plan of “Honest Abe”.

Read the True Life of “ABE” the letters and notes that he wrote, the man is not the GREAT MAN that history claims, as he stated himself “Black men will never be equal in thinking or functioning to be white man, and America would be better off it the slave had not been brought here. The only way to save the Union is to remove the black people from the country.” In the South, it seems to have worked by removing the history.

Thanks for taking the time to comment. You make claims about the role of black southerners in the Confederate army w/o providing any specific examples. Which black units are you referring to? What is your evidence that the United States destroyed documents that proved the existence of black units?

I fail to see what Lincoln has to do with any of this. Lincoln did indeed harbor racist views and expressed those views on a number of occasions. While I appreciate the comment, please be advised that future comments will be edited and/or deleted if you engage in insults or fail to be a productive member of this forum.

Black Confederates Why haven't we heard more about them? National Park Service historian, Ed Bearrs, stated, “I don't want to call it a conspiracy to ignore the role of Blacks both above and below the Mason-Dixon line, but it was definitely a tendency that began around 1910” Historian, Erwin L. Jordan, Jr., calls it a “cover-up” which started back in 1865. He writes, “During my research, I came across instances where Black men stated they were soldiers, but you can plainly see where 'soldier' is crossed out and 'body servant' inserted, or 'teamster' on pension applications.” Another black historian, Roland Young, says he is not surprised that blacks fought. He explains that “some, if not most, Black southerners would support their country” and that by doing so they were “demonstrating it's possible to hate the system of slavery and love one's country.” This is the very same reaction that most African Americans showed during the American Revolution, where they fought for the colonies, even though the British offered them freedom if they fought for them.

It has been estimated that over 65,000 Southern blacks were in the Confederate ranks. Over 13,000 of these, “saw the elephant” also known as meeting the enemy in combat. These Black Confederates included both slave and free. The Confederate Congress did not approve blacks to be officially enlisted as soldiers (except as musicians), until late in the war. But in the ranks it was a different story. Many Confederate officers did not obey the mandates of politicians, they frequently enlisted blacks with the simple criteria, “Will you fight?” Historian Ervin Jordan, explains that “biracial units” were frequently organized “by local Confederate and State militia Commanders in response to immediate threats in the form of Union raids”. Dr. Leonard Haynes, an African-American professor at Southern University, stated, “When you eliminate the black Confederate soldier, you've eliminated the history of the South.”

As the war came to an end, the Confederacy took progressive measures to build back up its army. The creation of the Confederate States Colored Troops, copied after the segregated northern colored troops, came too late to be successful. Had the Confederacy been successful, it would have created the world's largest armies (at the time) consisting of black soldiers,even larger than that of the North. This would have given the future of the Confederacy a vastly different appearance than what modern day racist or anti-Confederate liberals conjecture. Not only did Jefferson Davis envision black Confederate veterans receiving bounty lands for their service, there would have been no future for slavery after the goal of 300,000 armed black CSA veterans came home after the war.

. The “Richmond Howitzers” were partially manned by black militiamen. They saw action at 1st Manassas (or 1st Battle of Bull Run) where they operated battery no. 2. In addition two black “regiments”, one free and one slave, participated in the battle on behalf of the South. “Many colored people were killed in the action”, recorded John Parker, a former slave.

2. At least one Black Confederate was a non-commissioned officer. James Washington, Co. D 35th Texas Cavalry, Confederate States Army, became it's 3rd Sergeant. Higher ranking black commissioned officers served in militia units, but this was on the State militia level (Louisiana)and not in the regular C.S. Army.

3. Free black musicians, cooks, soldiers and teamsters earned the same pay as white confederate privates. This was not the case in the Union army where blacks did not receive equal pay. At the Confederate Buffalo Forge in Rockbridge County, Virginia, skilled black workers “earned on average three times the wages of white Confederate soldiers and more than most Confederate army officers ($350- $600 a year).

4. Dr. Lewis Steiner, Chief Inspector of the United States Sanitary Commission while observing Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson's occupation of Frederick, Maryland, in 1862: “Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number [Confederate troops]. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc…..and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army.”

5. Frederick Douglas reported, “There are at the present moment many Colored men in the Confederate Army doing duty not only as cooks, servants and laborers, but real soldiers, having musket on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets, ready to shoot down any loyal troops and do all that soldiers may do to destroy the Federal government and build up that of the rebels.”

6. Black and white militiamen returned heavy fire on Union troops at the Battle of Griswoldsville (near Macon, GA). Approximately 600 boys and elderly men were killed in this skirmish.

7. In 1864, President Jefferson Davis approved a plan that proposed the emancipation of slaves, in return for the official recognition of the Confederacy by Britain and France. France showed interest but Britain refused.

8. The Jackson Battalion included two companies of black soldiers. They saw combat at Petersburg under Col. Shipp. “My men acted with utmost promptness and goodwill…Allow me to state sir that they behaved in an extraordinary acceptable manner.”

9. Recently the National Park Service, with a recent discovery, recognized that blacks were asked to help defend the city of Petersburg, Virginia and were offered their freedom if they did so. Regardless of their official classification, black Americans performed support functions that in today's army many would be classified as official military service. The successes of white Confederate troops in battle, could only have been achieved with the support these loyal black Southerners.

10. Confederate General John B. Gordon (Army of Northern Virginia) reported that all of his troops were in favor of Colored troops and that it's adoption would have “greatly encouraged the army”. Gen. Lee was anxious to receive regiments of black soldiers. The Richmond Sentinel reported on 24 Mar 1864, “None will deny that our servants are more worthy of respect than the motley hordes which come against us.” “Bad faith [to black Confederates] must be avoided as an indelible dishonor.”

11. In March 1865, Judah P. Benjamin, Confederate Secretary Of State, promised freedom for blacks who served from the State of Virginia. Authority for this was finally received from the State of Virginia and on April 1st 1865, $100 bounties were offered to black soldiers. Benjamin exclaimed, “Let us say to every Negro who wants to go into the ranks, go and fight, and you are free Fight for your masters and you shall have your freedom.” Confederate Officers were ordered to treat them humanely and protect them from “injustice and oppression”.

12. A quota was set for 300,000 black soldiers for the Confederate States Colored Troops. 83% of Richmond's male slave population volunteered for duty. A special ball was held in Richmond to raise money for uniforms for these men. Before Richmond fell, black Confederates in gray uniforms drilled in the streets. Due to the war ending, it is believed only companies or squads of these troops ever saw any action. Many more black soldiers fought for the North, but that difference was simply a difference because the North instituted this progressive policy more sooner than the more conservative South. Black soldiers from both sides received discrimination from whites who opposed the concept .

13. Union General U.S. Grant in Feb 1865, ordered the capture of “all the Negro men before the enemy can put them in their ranks.” Frederick Douglass warned Lincoln that unless slaves were guaranteed freedom (those in Union controlled areas were still slaves) and land bounties, “they would take up arms for the rebels”.

14. On April 4, 1865 (Amelia County, VA), a Confederate supply train was exclusively manned and guarded by black Infantry. When attacked by Federal Cavalry, they stood their ground and fought off the charge, but on the second charge they were overwhelmed. These soldiers are believed to be from “Major Turner's” Confederate command.

15. A Black Confederate, George _____, when captured by Federals was bribed to desert to the other side. He defiantly spoke, “Sir, you want me to desert, and I ain't no deserter. Down South, deserters disgrace their families and I am never going to do that.”

16. Former slave, Horace King, accumulated great wealth as a contractor to the Confederate Navy. He was also an expert engineer and became known as the “Bridge builder of the Confederacy.” One of his bridges was burned in a Yankee raid. His home was pillaged by Union troops, as his wife pleaded for mercy.

17. As of Feb. 1865 1,150 black seamen served in the Confederate Navy. One of these was among the last Confederates to surrender, aboard the CSS Shenandoah, six months after the war ended. This surrender took place in England.

18. Nearly 180,000 Black Southerners, from Virginia alone, provided logistical support for the Confederate military. Many were highly skilled workers. These included a wide range of jobs: nurses, military engineers, teamsters, ordnance department workers, brakemen, firemen, harness makers, blacksmiths, wagonmakers, boatmen, mechanics, wheelwrights, etc. In the 1920'S Confederate pensions were finally allowed to some of those workers that were still living. Many thousands more served in other Confederate States.

19. During the early 1900's, many members of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) advocated awarding former slaves rural acreage and a home. There was hope that justice could be given those slaves that were once promised “forty acres and a mule” but never received any. In the 1913 Confederate Veteran magazine published by the UCV, it was printed that this plan “If not Democratic, it is [the] Confederate” thing to do. There was much gratitude toward former slaves, which “thousands were loyal, to the last degree”, now living with total poverty of the big cities. Unfortunately, their proposal fell on deaf ears on Capitol Hill.

20. During the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913, arrangements were made for a joint reunion of Union and Confederate veterans. The commission in charge of the event made sure they had enough accommodations for the black Union veterans, but were completely surprised when unexpected black Confederates arrived. The white Confederates immediately welcomed their old comrades, gave them one of their tents, and “saw to their every need”. Nearly every Confederate reunion including those blacks that served with them, wearing the gray.

21. The first military monument in the US Capitol that honors an African-American soldier is the Confederate monument at Arlington National cemetery. The monument was designed 1914 by Moses Ezekiel, a Jewish Confederate. Who wanted to correctly portray the “racial makeup” in the Confederate Army. A black Confederate soldier is depicted marching in step with white Confederate soldiers. Also shown is one “white soldier giving his child to a black woman for protection”.- source: Edward Smith, African American professor at the American University, Washington DC.

22. Black Confederate heritage is beginning to receive the attention it deserves. For instance, Terri Williams, a black journalist for the Suffolk “Virginia Pilot” newspaper, writes: “I've had to re-examine my feelings toward the [Confederate] flag started when I read a newspaper article about an elderly black man whose ancestor worked with the Confederate forces. The man spoke with pride about his family member's contribution to the cause, was photographed with the [Confederate] flag draped over his lap that's why I now have no definite stand on just what the flag symbolizes, because it no longer is their history, or my history, but our history.”

Resources:

Charles Kelly Barrow, et.al. Forgotten Confederates: An Anthology About Black Southerners (1995). Currently the best book on the subject.

Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia (1995). Well researched and very good source of information on Black Confederates, but has a strong Union bias.

Richard Rollins. Black Southerners in Gray (1994). Excellent source.

Dr. Edward Smith and Nelson Winbush, “Black Southern Heritage”. An excellent educational video. Mr. Winbush is a descendent of a Black Confederate and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

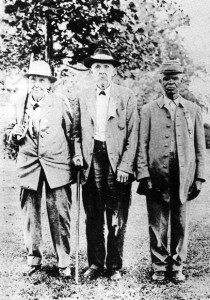

Enlisting in the Palo Alto Confederates in 1861 from his home in Palo Alto, Mississippi, at age 15 Andrew Martin Chandler was mustered into Co. F of Blythe's Mississippi Infantry, 44th Mississippi Infantry. He participated in several campaigns with his childhood playmate, friend and former slave, 17 year-old Silas Chandler.

Andrew was captured at Shiloh and was held prisoner in Ohio while Silas made repeated trips home to Mississippi to bring Andrew needed goods. Andrew was exchanged and he and Silas returned to their unit. Andrew was later wounded at Chickamauga. Army surgeons prepared to amputate his leg, but Silas used a piece of gold given to him by Andrew's mother to buy whiskey to bribe the surgeons to release him. He carried Andrew on his back for several miles and loaded him onto a boxcar heading to Atlanta – once there Andrew was taken to a hospital, where Silas cared for him until the family could join them – his leg, and possibly his life, were saved by Silas' attention and efforts.

I highly recommend that you browse through this blog's category of posts on Confederate Slaves/Black Confederates. Everything you've listed has been discussed at one point or another: http://cwmemory.com/category/the-myth-of-black-… The problem is the lack of academic scholarship on this subject. You referenced Jordan's book and that is a good place to start. However, Jordan does not trot out most of the claims that you've listed. There is no evidence that upwards of 65,000 black men fought as Confederate soldiers. In fact, the Confederate government barred their enlistment until the closing weeks of the war. Finally, the quote you attribute to Ed Bearrs is simply false. Bearrs has never said anything along those lines. Most of what you've included has been pulled from various websites – mostly from the SCV. Show me published sources from legitimate history journals or academic publishers.

The Black Confederate and Black History month

“There are at the present moment, many colored men in the Confederate Army doing duty…as real soldiers, having muskets on their shoulders and bullets in their pockets….” Frederick Douglas, former slave & abolitionist (Fall, 1861)

One hundred thirty-three years after the War, an African-American Scholar observed: “When you eliminate the black Confederate soldier, you've eliminated the history of the South…we share a common heritage with white Southerners who recall that era.

Historians have long held that black Southerners, free or slave, did not serve the Confederacy as soldiers, but worked instead as teamsters, laborers, cooks and personal servants. If those black men took up weapons in battle, this official version of history goes, it was because of circumstances and self-defense, not because they believed in the Southern cause. But recent scholarly works–many by African-American academics–have alleged a historical understatement and even a cover-up of blacks' real participation.

Twelve Reasons We Don’t Believe in Black Confederates

Many people reject the evidence that thousands of the South's 3,880,000 blacks, both free men and slaves, labored and fought, willingly, for the Southern Confederacy.

Why do they not believe, given the many accounts in the Official Records, contemporary newspaper reports, photographs, pension application records, and recollections of black Southerners? Here are 11 explanations.

1. It may force us to change what we believe. Changing our beliefs is troublesome and effortful. Most of us have always believed that both the Confederate and Union armies were all white, just like they are shown in the 1994 film Gettysburg.

2. It is not what most others believe. The leading guideline for adult behavior in questionable moral areas, according to the classic work of psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg is “What would people think?” (i.e., “what are other people doing”). We base our behavior—and ideas—on what others are doing, so that we appear “normal.” Since few others believe in black Confederates, we will not either, in order to fit in with the majority.

3. It might contradict a prejudice. Are we ready to accept that a black man could be every bit as brave, and every bit as dedicated, as a white man in combat? Rejecting the claim that blacks fought is consistent with a prejudice against blacks. Perhaps those who reject out of hand the idea of black Confederates are expressing their own prejudice against blacks.

4. It complicates our simple stereotype of blacks vs. whites as separate groups. But in truth, are these groups more alike than different? Maybe seeing them as different groups allows us to perceive differences that are not really there? A more complex perception is of one larger group with many diverse individuals, not of two groups of similar individuals. The simpler perception that fits a black versus white stereotype is consistent with the view that there were no black Confederates.

5. How do we now teach Civil War history in 10 minutes? How do we summarize the reasons for the war in a few sentences, if in fact thousands of black Southerners fired in anger at the Northern troops coming “to free them”? At least one Northern soldier put his frustration at that incident into the Official Record of the War of the Rebellion: “Here I had come South and was fighting to free this man,” the disgusted U.S. major wrote in his diary; “If I had made one false move on my horse, he would have shot my head off” (Barrow et al., 2001, p. 43).

6. It complicates the simple portrayal of the North as Good, driving out the “Wicked Southern Slave master.” How can Northern soldiers serve in the role as Angels of Mercy, if black Confederates shot at them?

7. It weakens support for the claim that the War was About Slavery

8. Many whites disbelieve that there were black Confederates because of “White Guilt.” Many white Americans feel undeserving of their wealth. Certainly, many are undeserving. Some give a small part of their wealth to the poor, and this seems to make them feel better. Others hire the poor to work for them—and then bask in their role as benefactors. Massachusetts writer—and abolitionist– Henry Thoreau saw through this chimera 20 years before the War. He wrote concerning charity towards the poor at the end of the chapter “Economy,” in his masterpiece Walden. Regarding his wealthy friends who “helped” the poor, by paying them to work in their kitchens, Thoreau wrote: “Let them work in their own kitchens.”

One target for giving wealth has traditionally been black causes. A major recipient has been the NAACP, which endorses a movement to shift massive wealth to former slaves. Establishing that some of these slaves supported the Southern States, and that some blacks today, descendants of those slaves, still support the ideals of the Confederacy (and there were other ideals besides slavery), is inconsistent with the fundamental causes of White Guilt.

9. It is inconsistent with the culture of Victimhood. If blacks chose to fight for the South, how can blacks be passive, helpless, unwilling victims? One black liberal dismissed evidence that blacks fought for the Southern Confederacy by referencing the “abused wife syndrome”: An accusation that these poor helpless blacks were victims and unable to act with volition and control over their environment. But what do we say of the blacks captured by Yankees who escaped and returned to their units?— Or of the more than 40 blacks attending the 1890 UCV Reunion, pictured in another essay? One has to believe an “abused wife syndrome” that is powerful indeed, to explain the activities of these black Confederates.

10. It brings up the annoying question: Why did blacks fight? If the reasons blacks fought for the South include the same reasons whites fought for the South, or any of the same reasons that anyone fights for any cause in any war, then we have to look at those fighting black Confederates as deliberative, volitional, reasoning, diverse, individuals, just like the whites we talk about, when we talk about why whites fought for the South. This topic is dealt with as a separate essay.

11. It brings up another annoying question: Why did anyone fight for the North? No one really knows why men go to war to fight. Once they get there, they don't fight for their flag, or their country, or God. They fight for their comrades. Some of the issues involved in the discussion of why men fight are presented in another essay in this series, “Why Did Blacks Fight for the Confederate States of America.”

12. We Want to Believe the War Was About Slavery

Accepting that thousands of blacks fought for the Confederate States of America forces us to rethink the common assumption that the War was “about slavery.” Surely no one would dismiss slavery as an important factor. But to most modern Americans, slavery was the factor, perhaps the only factor. Again, to the extent that we believe that thousands of black Confederates fought for their country, our belief in slavery as the cause of the War is threatened. This need for cognitive balance is examined at length in another essay. To summarize that essay: We ask, “what balances the deaths of 600,000 Americans during the years 1861 to 1865?” We need some reason to balance that great tragedy. What is it?

Getting even for Fort Sumter? No. Settling States Rights issues? No– That answer never seems to explain why so many Americans died. Settling Tariff issues? No– Same shortcoming, plus, few modern Americans can stay awake during any discussion of tariff issues. How about, to Preserve our Great Experiment in Democracy! No– it is hard to sell this idea to modern Americans as the reason that more than half a million Americans died. The argument typically holds that had the Confederacy established itself, then there would have been more secessions, until ultimately we would have had a separate country, or two, in everyone’s back yard.

Finally, the End of slavery: Yes: Now there’s a reason we can celebrate: Slavery is bad; The South had slavery; therefore the South was bad and the Good North fought against the South, and slavery ended. Any child can grasp this argument; try explaining tariff issues to that person. Try explaining States Rights to that person—try explaining the issue of free trade and Northern versus Southern import and export economies—try explaining the diverging cultural bases of the North and the South. You will get a big yawn. Consider Ken Burns’s popular and acclaimed The Civil War—the most popular PBS series in history. To his great credit, Mr. Burns shows the appalling tragedy of 600,000 thousand dead Americans. And running throughout this 11 hour drama is the theme that ending slavery was the reason for these deaths. At one point a black woman historian makes that point explicit: The Union lifted the War to a higher plane, she explains. Clearly, Burns has accepted the idea that the War was “over slavery”—if only to give some sense to the TV audience who might wonder why America fought itself, and to do it in the TV schedule he had to work with.

Ultimately we believe the War was about the Ending of Slavery because that is the only cause that provides the cognitive balance we need.

The great evil of more than 600,000 deaths “balances” in our minds against the great evil of slavery.

“Ending Slavery” provides that cognitive balance for the War of 1861– Never mind that slavery ended everywhere else in the world without bloodshed. Never mind that other factors explain that the North and South became different countries long before 1860. Slavery provides that simple cognitive explanation.

Any evidence that blacks fought for the South is inconsistent with the notion that the War was only about slavery.

References

Adams, Charles. (2000). When in the Course of Human Events: Arguing the Case for Southern Secession. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Barrow, C. K., Segars, J. H., & R.B. Rosenburg, R.B. (Eds.) (2001). Black Confederates, Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna.

Who are these black academic historians? Please do not point to Walter Williams since he is an economist and has never published anything serious in the field of history. Even if we assume that your claims are true you still have not provided any evidence for the existence of large number of black Confederates. Barrow and Segars is not a serious study and the Adams book is not about this subject at all.

Please take the time to read Bruce Levine's _Confederate Emancipation_ (Oxford University Press). It's not long and is one of the few academic studies that addresses the role that blacks played in the Confederate Army, the debate itself that took place in the Confederacy, and the evolution of the myth of black Confederates. Until then this little thread is closed. You've been given every opportunity to provide new information on the subject. Thanks for your understanding.

Kevin,

“Stacey” is merely cutting and pasting from web sites, and not even bothering to do her own writing, much less her own thinking.

Marc

You are absolutely right and as you might suspect it is impossible to engage someone who approaches the study of history from this angle. Information is presented without any understanding of source or analysis. Even a cursory glance at this blog would demonstrate that these arguments have been presented over and leads to the same dead end.

The blacks, both slave and free, who were captured by the Union army and forced into “service” for the north did not fight voluntarily either. Neither did the multiplied thousands of poor northern whites who were conscripted into service against their will and made to fight for Uncle Sam for a cause they did not support. These Yankee soldiers, both black and white were essentially slaves to Uncle Sam.

Thanks for taking the time to comment. Unfortunately, your comment betrays very little understanding of the relevant facts. First, blacks were not drafted into the Union army – they volunteered. Second, you are correct in noting that after 1862 most white northerners who served were drafted. That said, the issue of why men fought is much more complicated and I suggest you pick up any number of books for an introduction. I suggest you start with Chandra Manning's What This Cruel War Was Over or James McPherson's Why Men Fought. Thanks again.

I don't think you are correct in stating that most white northerners who served after 1862 were drafted. The Union didn't begin conscripting men until mid-1863. And even then, the draft was largely used to encourage enlistment, and since the majority of those drafted either paid commutation fees or hired substitutes, a relatively small percentage of Union soldiers after 1862 were draftees. Please correct me if I'm wrong on this.

That was a sloppy response on my part. Thanks.

According to McPherson, the smaller Confederate army included about 120,000 conscripts and 70,000 substitutes (24 percent of the army). In contrast the Union army contained many fewer conscripts (46,000), due in large part to the bounties Marc points to, but many more substitutes (118,000). That's still only about 6 percent when the two groups are combined. The average Johnny Reb was significantly less likely to have been a willing volunteer than the average Billy Yank.

And aren't you supposed to be working? 😉

I always have time to respond to a comment. 🙂

I'm not sure more white men were drafted post-1862 than enlisted. According to Nevin (“The Organized War 1863-1864”), 168,649 were drafted in the four draft calls of 1863 and 1864, including 74,2027 substitutes. I wager there were more than 170,000 enlistees after 1862 (Lincoln called for 300,000 in October 1863 alone.)

As a tiny example, I had two kin from upstate Maine (brothers) who were drafted in August 1864. Out of more than 30 men in their draft sub-district, they were the only two who ended up in the service. All the rest never showed, or weren't physically qualified, or hired substitutes. I imagine that was not too unusual a result.

You do realize, don't you, that the first Confederate Conscription Act was passed in April 1862, nearly a full year before the first US Conscription Act. The Confederate Conscription Act initially covered white males ages 18 to 35 and allowed for the hiring of substitutes. Later, the age range was expanded from 17 to 50. While the initial act allowed for some exemptions to maintain agriculture and industrial production, it did not provide an exemption for overseers of plantation slaves. On October 11, 1862, the Confederate Congress passed the so-called “Twenty Slave Law” exempting 1 white man from the draft for every 20 slaves owned. It was justified as a safeguard for agricultural production and against slave rebellions. In some areas with large slave populations, fear of servile insurrection produced acceptance, but in other areas, it caused great controversy among whites who owned few or no slaves about turning it into a “poor man's war.” The exemption was modified and, mostly made harder to qualify for in order to avoid able-bodied white men from taking jobs as overseers to avoid the draft. In both North and South, one of the most frequently used bases for applications for writs of habeas corpus was to avoid the draft.

As for forcing Blacks, when the 54th Massachusetts, one of the first, maybe the very first, black US Army regiments was being formed, black men travelled from all over the country, especially New York and Pennsylvania, to enlist. Prominent free and freed Blacks put themselves on the line for it. Frederick Douglass wanted to enlist but reluctantly gave in to arguments that he could do more good for the war effort outside the army. However, two of his sons, Lewis and Charles enlisted in the 54th Mass. Lewis (not some aging former slave) was the first sergeant-major of the regiment and fought at Battery Wagner. So many volunteers arrived to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts that a 2nd Regiment, the 55th Massachusetts was formed. The 55th included 222 volunteers from Ohio and fought at the Battle of Olustee among others.

BTW, one thing different about conscription and genuine slavery is that, in conscription unlike chattel slavery, the government does not get to sell you to another army and it doesn't own your wife and children with the ability to do the same to them.

The creepiest thing about this whole “black Confederate” thing is the implicit endorsement of paternalistic dehumanization that it entails from groups like the SCV and others. Think about it, would you describe the actions of any other human being who was forced into coerced labor as “faithful,” “loyal,” or any other paternalistic term? Describing slaves this way denies them of their humanity by likening their perceived actions to that of a pet dog. Weather Confederate veterans groups intend this or not, its what their peculiar revisioning of the master-slave relationship ultimately does and in that sense, they are adopting the most dehumanizing tactics of the 19th century pro-slavery theorists. I realize that there are some Africn-Americans today who seem to share some kind of affinity for a constructed Confederate past. Fine. But they weren't alive in the 19th century. By the way, great to meet you at the SHA conference, Kevin.

Excellent point.

Dear Ms. Southern,

You will notice that your comment has been deleted. Please understand that I do not allow people to post on this site who have issued threats against me on other sites. You will notice that there are plenty of comments on this site written by those who disagree with something I've written. While there was nothing in this present comment that was insulting your past conduct leaves me no choice but to prevent you from posting here.

Your comment had very little to do with this post. Walter Williams is not a historian and it is clear that you have not taken the time to even read Lee's own words on the subject of slavery.

Sincerely,

Kevin Levin

I have followed your site for the last couple months, and have been somewhat surprised to see so much discussion about “Black Confederates”. In all the years I have studied the Civil War this issue has never crossed my mind, or have I read anything of significance on this issue. I'm a novice on this issue, but your comment, “Almost all the cases of black confederates turn out to be slaves following masters”, just seems like common sense.

Recently, I was doing research on my great grandfather who was a member of the 62nd Alabama and fought at Ft. Blakely, Ala, the last battle of the Civil War. I came across this article in “Combat Magazine”. The following quote is from that article about the battle of Ft. Blakely If this is true, it may be the closest a black regiment came to fighting for the Confederacy.

“One of the black regiments, the 73rd USCT was from Louisiana, and originally all of its members were Freedman from the New Orleans area. They were land owners, and some were even slave owners, who in the beginning had decided to fight for the South. But when they realized the southern hierarchy was using them as a propaganda tool and had no intention of letting them fight; they offered their services to Union General Benjamin Butler when the Yankees took New Orleans after the southern army evacuated the city.”

http://www.combat.ws/S3/BAKISSUE/CMBT04N2/BLAKE…

I enjoy your site. Keep up the good work.

I made a conscious decision to take on this issue since it is such a controversial issue within certain circles and is a central problem with our Civil War memory. The reason you haven't read anything substantial is because very little has been written on the subject. Hopefully, that will change in the coming years.

Harvey,

Great care has to be taken in applying anything coming out of Louisiana to the rest of the states that joined the Confederacy. Louisiana's experience was unique because so much of it had taken place under French and Spanish rule. Both had slavery but their attitudes on race, particularly the offspring of white fathers and slave mothers, differed markedly from the experience of the English colonies and the country that arose from them. I'd recommend Ira Berlin's “Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South.” He does a magnificent job in explaining all of this.

The notion of honoring these men for their “service” is nothing more than a perpetuation of the loyal slave myth. They did “serve,” as slaves must. If Wood and the UDC want to honor the memory and lives of these men, then they should put up markers clearly stating that they were slaves, period. Frankly, they are using these men, as did the men's owners and the Confederate army, for their own purpose, which in this case it is to make them posthumous apologists for the CSA.