Update: Is Jackson’s dark complexion just an accident or is this an attempt to blur the racial line?

Update: Is Jackson’s dark complexion just an accident or is this an attempt to blur the racial line?

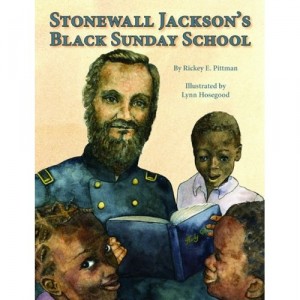

If you didn’t know any better one might think that Confederate leaders were at the forefront of the civil rights movement. Case in point is the popular and misunderstood story of Stonewall Jackson’s black Sunday School which he established in Lexington, Virginia in 1855. Most of the stories that you will come across Online or in non-academic books tend to wax poetic about the benefits of these classes for the areas free and enslaved blacks. There is no shortage of stories of blacks praising Jackson or dedicating stained-glass windows long after his death and the end of the Civil War. All of this is interesting, but rarely are we given anything that approaches analysis of how the school functioned in slaveholding Virginia in the period after Nat Turner’s insurrection. Even James I. Robertson, who authored the most thorough biography of Jackson, fails to provide a sufficient analysis of the broader conditions that shaped Jackson’s Sunday School. Robertson cites the widely held assumption that “the more uninformed a slave was about everything, the more docile he tended to be”, the Virginia code that forbade the teaching of slaves to read, and Jackson’s apparent defiance. That’s about it. We are left with an image of a defiant Jackson who would not allow Virginia law to stand in his way of saving souls. This view is pervasiveness throughout much of the popular literature. Consider Rickey Pittman’s new book, Stonewall Jackson’s Black Sunday School:

In autumn 1855, slaves and free black men, women, and children first made their way to the Lexington Presbyterian Church to attend Sunday school. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, a professor at the Virginia Military Institute, stood as the superintendent of this school. Although it was illegal under Virginia law to teach blacks to read and write, Jackson believed all men, regardless of race, should have the opportunity to receive an education. To these students, Professor Jackson was a leader and mentor who taught them more than just reading and writing. He instilled in them the word of God. Even after he left to join the Civil War, he prayed for his students and sent them money for Bibles and hymnals. Through Jackson’s leadership, many of his Sunday-school students went on to become community leaders, ministers, and educators. This lesser-known tale of the Confederate leader shows young readers another side of the man known in battle as “Stonewall.”

Earlier I referenced Nat Turner and I did so because it is crucial to understanding this story. Charles Irons does a magnificent job of analyzing the degree of cooperation between white and black evangelicals in Virginia through the early 1830s. He notes that by 1830 there one-quarter of black Virginians (115,000) had been converted to evangelical Christianity and thousands more practiced outside of the church. In addition, Turner’s claims that God had inspired him to rise up against the white population worked to reinforce growing concerns among white evangelicals as to their ability to safely monitor black gatherings. Irons is instructive here:

Gripped by fear and mistrust for several months, white Virginians struggled to adjust to the sobering fact that converted slaves could unleash such savagery. Some, particularly nonslaveholders from the western portion of the commonwealth, suggested that only a general emancipation could save the state from racial Armageddon and pushed for a constitutional convention to consider such a measure. Others, including some white evangelicals still shocked by August’s carnage, favored simply denying slaves the privilege of religious expression. Stark choices: emancipation or an end to evangelization. Within tow years, however, white evangelicals had found a way to move forward without either destroying black religion or freeing their slaves. No single ideologue emerged to articulate the new policy of constant white supervision right away; politicians and churchgoers independently stumbled toward the formula of aggressive oversight and proselytization. (p. 143)

Within this context, Jackson’s school makes perfect sense, though it should be pointed out that a school had been established in Lexington as early as 1843. While our popular perceptions paint Jackson as some kind of liberator who was ahead of the curve, Irons’s analysis provides us with a clearer understanding of how the school reinforced slavery and white supremacy in Lexington and the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson admitted as much himself when he noted that God had placed the black race in a subordinate position. Constant oversight allowed Jackson and the rest of the white population to continue to proselytize and at the same time monitor his black students’ understanding of themselves in relationship to God and the white community. One can only wonder what Jackson would have said to a student who put forward the notion that slavery stood in contradiction to God’s law.

Let me point out that the goal here is not to demonize Jackson. I have no problem with people who choose to celebrate Jackson’s work within the black community. As historians, however, our job is to understand how churches functioned in a slaveholding society and how those institutions evolved in response to various challenges. As much as we need to be sensitive to Jackson’s personal motivation we must never forget that he did not operate in a vacuum.

Off topic here,but this could show southerners were not tyrannical and oppressive towards slaves. Anyone has a problem with General Jackson and think there’s no way he could’ve worried about slaves one way or another,can study on this. This is the first example that comes to mind. I can’t recall the gentlemans name . I can’t recall why he was given a ton of lashes with a bull whip. His picture is pretty well known . A black slave with his back to the camera . His back was totally destroyed by a bullwhip. The overseer at the plantation did it. The plantation owner was called to the slave quarters by a slave. When the owner got there,he blew his stack after he saw what happened to that mans back,by a bullwhip. The slave driver did it. That’s all the plantation owner needed to hear. He blew his stack.He fired the slave driver that abused the slave that way. Then he called for a Dr. to come tend to the slaves back. Dr. told the plantation owner,that slave would be sidelined for a while. No problem. The slave was in bed for like 3 weeks. . The plantation owner was like “okay”. He checked on him regularly . I bring this up because people sometimes think the General was not that way towards blacks at all. Some that do accept the story,think of it as an isolated incident. It wasn’t . A lot of white folk were civil towards slaves. I’m not trying to put a happy face on slavery. It sucked. However There was a lot of plantation owners and street level people,that didn’t look at slaves as property,or something less than human. The General was one. The story I mentioned earlier here about the plantation owner,was one of them. You just got so many people today wanting to create their version of slavery. God forbid it if you actually find something positive going on in the south during slavery. However you got people out there like the General. However no one wants to believe he actually looked at slaves as humans. So given the character of the General along with his religious beliefs,it’s a very easy conclusion to come to that he was pretty much on the level with blacks

So you assume Jackson was only there to monitor the slaves education, to assure there would be no uprisings and to instill white supremacy. The idea that he may have been doing it out of Christian compassion escapes you.

And here I thought “Christian compassion” precludes holding other people as property. Silly me.

Hi first I live in Roanoke Va and have seen the stained glass window in the black Church .

that portrays Jackson last moments and his last words

I would like to point out that both Jackson and RE Lee both believed that slavery was

immoral

If the war had been about slavery and Nether Lee or Jackson would never have the left the US army

To begin to understand the situation Jackson found himself in,we must look through the eyes of the society as a whole during that period of our country’s history. George Washington wished to free the slaves but knew the people were not ready for it at that time( either group).It has been stated by some that Jackson’s times were like when Thomas Paine’s book “Common Sense”was published.Paine’s ideas were dangerous to the powers at be.Still, they survived and eventually thrived.It is another interesting thought that Jackson was taught by a slave lady named Fannie to read and who was very kind to him.We must put things into proper context and perspective. Jackson read St. Paul’s words that “slaves should obey you masters” Jackson heeded to a Higher Master & taught the truth as given by “St. Paul’s Master. Judge the work & the results.God will be the final Judge.

“Update: Is Jackson’s dark complexion just an accident or is this an attempt to blur the racial line?”

You may be on to something here. Recently, I re-watched the infamous scene in Gods & Generals where Jackson and Jim Lewis talk about the slavery and the General discusses emancipation and the enlistment of Black soldiers. I noticed Jackson talks down to Lewis: “One way O’ T’OTHER, your people will be free.” He doesn’t speak to anyone else like this anywhere else in the film.

“In the film.” Let that remind you it was the producer’s view of it.

Those who want to use Prof. Robertson's book to try to prove Jackson was “the black man's friend” misuse it. Prof. Robertson very clearly says Jackson thought it was his duty as a Christian to save souls, even the souls of slaves. He also tells us that Jackson gave monthly reports to the owners on each slave's attendance and progress. While I think Robertson gives the best explanation for Jackson's participation in the school, I also think the owners saw the benefit you mentioned, Kevin, in having their slaves participate.

Right, but as I said in the post, even Robertson fails to provide a satisfactory analysis with which to understand Jackson's black Sunday School. Jackson's school fits neatly within the slave system of Virginia as a means to maintain white supremacy in a post-Nat Turner world. He may have been “saving souls” but their bodies would remain under the complete control of their owners and free blacks would remain under the watchful eye of the white community.

I couldn't remember the title of this earlier (but I alluded to it) so let me share just another primary resource of sermons for slaves as deemed appropriate by slave holding whites.

Glennie, Alexander Rev. Sermons Preached on Plantations to Congregations of Negroes (Charleston: A.E. Miller, 1844). Glennie was the rector of All-Saints Parish in Waccamaw, SC. This text has been reprinted by Somerset Place Foundation, Inc. (Readers simply MUST go to Somerset Place http://www.nchistoricsites.org/somerset/somerse…)

Ok back to lurking (I think)…

Kevin, I enjoy this post and it reminds me to take a moment to read a series of published sermons by a Southern minister deemend appropriate by him for Southern blacks.

In light of that I want to share with the readers of this blog the following reference: Jones, Charles Colcock. The Religious Instruction of Negroes in the United States (Savannah: Thomas Purse, 1842), also available online at http://books.google.com/books?id=Jg4CAAAAYAAJ&p… OR http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/jones/jones.html

Jones' publication is even more interesting when you read alongside Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). Jones's catering to the religious needs of the enslaved community did not stop Jane from wanting to get out of slavery.

Of course the most interesting of Central Virginia's Black churches was the First African Baptist headed by Robert Ryland, ran to a large degree by the free black deacons and attended by enslaved and free blacks and which is documented in several works on antebellum Black religiosity, antebellum Richmond, etc.

Nice to hear from you and thanks for passing along the links. I've read sections of Colcock's book, which is quite interesting and helpful in better understanding how Christianity was used to maintain the slave system. That publication date of 1842 places in direct response to Turner's insurrection.

Kevin-Religion was an extremely touchy point in the slavery debate. The 18th Century abolitionists, many of whom came at the subject from an Enlightenment/natural rights perspective could not get under the white Southern plantation caste's skin the way that the 19th Century abolitionist movement, with its evangelical Protestant foundation could.