Earlier today I finished reading Michael J. Bennett’s essay “The Black Flag and Confederate Soldiers: Total War from the Bottom Up” which is also published in Andy Slap and Michael Smith eds., This Distracted and Anarchical People: New Answers for Old Questions about the Civil War-Era North

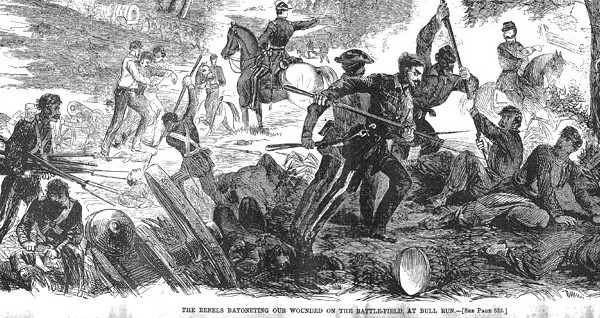

Earlier today I finished reading Michael J. Bennett’s essay “The Black Flag and Confederate Soldiers: Total War from the Bottom Up” which is also published in Andy Slap and Michael Smith eds., This Distracted and Anarchical People: New Answers for Old Questions about the Civil War-Era North. In his essay, Bennett explores accounts of massacres throughout the war that function as a case study of how various factors shaped what Mark Neely calls the “limits of destruction.” After exploring evidence of atrocities on the First Bull Run battlefield, Bennett makes the following point, which I think is relevant to the ongoing discussion taking place elsewhere about the recent FCWH conference in Gettysburg and the call to move our public memory of the war beyond a heroic understanding of soldiers and battle.

How can these accounts be folded into the current narrative of the war? The answer is that they cannot. The best way to reach an understanding of what really happened at Bull Run and the events that followed is to rethink what soldiers when through in combat. Watching GIs commit “un-American acts” against German soldiers in Italy during World War II pushed the combat artist George Biddle to seek a reassessment of the soldiers’ combat ordeal. He wrote that it was unfair for civilians to think of soldiers as heroes or stars. Instead, he thought it more appropriate that soldiers be viewed as survivors of a great disaster like a mine collapse or a burning building. Only then could civilians truly understand the desperate circumstances and decisions under which soldiers fought. (p. 150)

Bennett focuses specifically on the use of the black flag in Confederate ranks as well as more disturbing behavior such as beheading and the mutilation of bodies. While a good deal of focus is placed on Bull Run, the author references other battles as well such as Front Royal, Winchester, Fredericksburg, Seven Days, Wilderness, Chickamauga, and Stones River. Keep in mind that when I first came across Bennett’s piece in the table of contents I immediately assumed it was about Confederate atrocities committed against black Union soldiers. Interestingly, Bennett only briefly touches on these well documented cases. The bulk of his time is spent looking at white on white atrocities, which is instructive.

This led me to question whether we have pushed away these stories into certain compartments that are more easily digested. I wonder if it is easier to acknowledge the dark side of our civil war when it come to blacks and white massacring one another on a select few battlefields late in the war or among bushwhackers on the frontier, where we accept that Americans were somehow hardwired to engage in more brutal acts of warfare? Does that preserve our most popular landscapes in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania for the kind of violence that we can more comfortably commemorate and even celebrate?

Finally, to return to the passage above, can we introduce atrocity stories into our interpretations of places like Gettysburg and Bull Run without having to fundamentally shift our understanding of the men who fought there?

Excerpt from another legal case. Seems the holier than now City of Boston was segregating black students from white students long before the war. (1849) Sarah C. Roberts v. The City of Boston. SUPREME COURT OF MASSACHUSETTS, SUFFOLK 59 Mass. 198; 1849 Mass. LEXIS 299; 5 Cush. 198, November, 1849

This was an action on the case, brought by Sarah C. Roberts, an infant, who sued by Benjamin F. Roberts, her father and next friend, against the city of Boston, under the statute of 1845, c. 214, which provides that any child, unlawfully excluded from public school instruction in this commonwealth, shall recover damages therefor against the city or town by which such public instruction is supported.

. . . . .

“Admissions of Applicants. Every member of the committee shall admit to his school, all applicants, of suitable age and qualifications, residing nearest to the school under his charge, (excepting those for whom special provision has been made,) provided the number in his school will warrant the admission.

“Scholars to go to schools nearest their residences. Applicants for admission to the schools, (with the exception and provision referred to in the preceding rule,) are especially entitled to enter the schools nearest to their places of residence.”

“At the time of the plaintiff’s application, as hereinafter mentioned, for admission to the primary school, the city of Boston had established, for the exclusive use of colored children, two primary schools, one in Belknap street, in the eighth school district, and one in Sun Court street, in the second school district.

“The colored population of Boston constitute less than one sixty-second part of the entire population of the city. For half a century, separate schools have been kept in Boston for colored children, [**4] and the primary school for colored children in Belknap street was established in 1820, and has been kept there ever since. The teachers of this school have the same compensation and qualifications as in other like schools in the city. Schools for colored children were originally established at the request of colored citizens, whose children could not attend the public schools, on account of the prejudice then existing against them.

“The plaintiff is a colored child, of five years of age, a resident of Boston, and living with her father, since the month of March, 1847, in Andover street, in the sixth primary school district. In the month of April, 1847, she being of suitable age and qualifications, (unless her color was a disqualification,) applied to a member of the district primary school committee, having under his charge the primary school nearest to her place of residence, for a ticket of admission to that school, the number of scholars therein warranting her admission, and no special provision having been made for her, unless the establishment of the two schools for colored children exclusively, is to be so considered.

Again, what exactly is this in response to? Have I ever suggested that racism and discrimination was anything less than a national problem. If you are interested in the history of race and politics in Boston I highly recommend Stephen Kantrowitz’s new book, More than Freedom: Fighting For Black Citizenship in a White Republic – 1829-1889. This is getting to be oh so boring.

M.D. Blough said, “Black codes existed before the war. However, in slave states, there was relatively little need for them, depending on how many free/freed blacks there were, because most blacks were kept in line by the power of slavery, mostly enforced by individual slave owners, not the law.”

Sorry but you been reading too much of the fiction tale “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Black codes did not exist in the South before the war, because most slaves were treated as family, therefore rendering black codes unnecessary. Only a minor few slaves were mistreated by their Southern owners. The maltreatment of slaves was perpetrated by the Yankee and English slave traders. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson actually had slaves on the auction block beg to be bought by him, because Jackson treated his slaves so well. Social Security and welfare and food stamps were not necessary either. No slave was impoverished and their owners took very good care of the slave until they died of old age.

When the North discarded their slaves they were sold in the South for profit.

M.D. Dlough further said, “However, during Presidential Reconstruction, former rebel states put draconian Black Codes in effect that tried to get as close to slavery as possible without the auction block.”

Here again the claim is that slavery and black codes are all about the South. Last time I checked Michigan is in the North. The “black code” legal case I mentioned above occurred in Michigan, NOT the South, AND twenty five years AFTER the war. (1890)

And as Kevin Levin said, “If you want to be taken seriously I suggest including relevant references to secondary sources or the documents themselves if you have access to them . . . . Perhaps you should step outside of your personal morality play for a few minutes.

You said: “Only a minor few slaves were mistreated by their Southern owners. The maltreatment of slaves was perpetrated by the Yankee and English slave traders. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson actually had slaves on the auction block beg to be bought by him, because Jackson treated his slaves so well. Social Security and welfare and food stamps were not necessary either. No slave was impoverished and their owners took very good care of the slave until they died of old age.”

Thanks Terry. I’ve read all I need to read from you. How silly.

I concur with Kevin.

Here’s one for your “war crimes.” Francis Key Howard (1826 – 1872) was the grandson of Francis Scott Key and Revolutionary War colonel John Eager Howard. Howard was the editor of the Baltimore Exchange, a Baltimore newspaper sympathetic to the Southern cause. He was arrested on September 13, 1861 by U.S. major general Nathaniel Prentice Banks on the direct orders of general George B. McClellan enforcing the policy of President Abraham Lincoln. The basis for his arrest was for writing a critical editorial in his newspaper of Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and the fact that the Lincoln administration had declared martial law in Baltimore and imprisoned without due process, George William Brown the mayor of Baltimore, Congressman Henry May, the police commissioners of Baltimore and the entire city council.[1] Howard was initially confined to Ft. McHenry, the same fort his grandfather Francis Scott Key saw withstand a British bombardment during the War of 1812, which inspired him to write The Star Spangled Banner, which would become the national anthem of the United States of America. He was then transferred first to Fort Lafayette in Lower New York Bay off the coast of Brooklyn, then Fort Warren in Boston.

He wrote a book on his experiences as a political prisoner completed in December of 1862 and published in 1863 titled Fourteen Months in the American Bastiles.[2][3] Howard commented on his imprisonment;

“When I looked out in the morning, I could not help being struck by an odd and not pleasant coincidence. On that day forty-seven years before my grandfather, Mr. Francis Scott Key, then prisoner on a British ship, had witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry. When on the following morning the hostile fleet drew off, defeated, he wrote the song so long popular throughout the country, the Star Spangled Banner. As I stood upon the very scene of that conflict, I could not but contrast my position with his, forty-seven years before. The flag which he had then so proudly hailed, I saw waving at the same place over the victims of as vulgar and brutal a despotism as modern times have witnessed.”

It appears that war crimes were overwhelmingly committede by Confederate forces, not Union. Is that correct? And if so, would it be true to say that the victims of Confederate atrocities were likely to be first Black soldiers, second White Union soldiers from Confederate states, and only thirdly White soldiers from Union states?

Joseph T Wilson in The Black Phalanx says that White North Carolina Unionist soldiers were among the victims of the Fort Pillow massacre; is that confirmed?

It never ceases to be amazed how Yankees refuse to believe the sins of their fathers. It ‘s all about the evil South and the evil Confederates. But check out Ferguson v. Giles (1890). What you say, black codes in Yankee land?

In Ferguson v. Giles (1890), the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that William Ferguson’s civil rights were violated when he was expelled from a Detroit restaurant for refusing to dine in its “colored” section. In fact Yankee land invented the first “black codes.”

Terry,

If you want to be taken seriously I suggest including relevant references to secondary sources or the documents themselves if you have access to them. I don’t think London John was making a moral point about North v. South. He asked a question. Perhaps you should step outside of your personal morality play for a few minutes.

I think you have proven my point. No matter what I present as evidence it is never good enough. I gave you the best evidence in existence. The actual court case. It’s written in stone. What more do you want?

You come here with a chip on your soldier as if you need to educate all of us that racism existed beyond the South. We all know this. In fact, you can find multiple posts on the pervasiveness of racism and other problems that pervaded the nation throughout its history.

I simply asked you to follow up with an example of what you are thinking about. Thanks for taking the opportunity to do so.

Black codes existed before the war. However, in slave states, there was relatively little need for them, depending on how many free/freed blacks there were, because most blacks were kept in line by the power of slavery, mostly enforced by individual slave owners, not the law.

However, during Presidential Reconstruction, former rebel states put draconian Black Codes in effect that tried to get as close to slavery as possible without the auction block. These were some of the primary actions that angered the U.S. Congress and led to Radical Reconstruction and the struggle with Andrew Johnson that culminated with his Impeachment and narrow acquittal in his Senate trial.

I think Drew Gilpin Faust’s “Republic of Suffering” bears on this subject, as well. I’ve thought about this idea every time I see photographs of Civil War battlefields strewn with bodies. How could seeing that kind of carnage not affect the soldiers? We know it deeply affected soldiers in World War I, and there’s no reason to imagine it was different for Civil War soldiers. I put in a second plug for Keegan, too.

The long-term effects of war on veterans are explored in great detail in James Marten’s Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America.

Excerpt from “The Slaves’ War,” The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves.

by Andrew Ward

Female slaves had a special horror of rape at the hands of Yankees. In Georgia “there was a heap of talk about the scandalous way them Yankee soldiers been treating Negro womans and gals.” Black women were “a-feared to breathe out loud come night,” Rufus Dirt recalled, “and in the day time they didn’t work much cause they was always looking for the Yankees.” To protect their womenfolk from rape, a group of black men on one Southern plantation placed all of them in one building and posted a guard outside.

“There were soldiers in the woods,” recalled Julia Francis Daniels of Texas, “and they had been persecuting an old woman on a mule.” Convinced they would come for her next,”I got so scared I couldn’t eat my dinner. I hadn’t got any heart for victuals.” “Wait for Pa, “her brother told her.” He’s coming with the mule, and he’ll hide you out.” So Julia “got on the mule in front of Pa, and we passed through the soldiers, and they grabbed at me and said, ‘Give me the gal! Give me the gal!’ Pa said I fainted plumb away,” but he got her through.

At least the issue was raised back then. The Virginian guerrilla leader Mosby took pains to distance himself from the savagery in Missouri and Kansas, even under provocation. Nowadays, thousands of civilians can be bombarded without warning and with impunity. A partisan embedded press corps hardly mentions them. The uniformed perpetrators are hailed as heroes, while the safest place on the modern battlefield is often inside a uniform.

Personally I do not think the introduction of such atrocities will change the legendary status of the Civil War and those that fought it. The soldier of that war is propped up on an eternal pedestal in American memory. I think Shelby Foote said it best when attempting to discuss why so many are drawn to that period of history; we secretly want to be there. It was the great adventure in the adolescence of the U.S. and “sadly,” we missed out.

As far as the inclusions of “atrocities” in the war, I am not convinced that such an inclusion would alter the perception of the conflict. America has an odd military history that is unique. Colonialists have always engaged in a variation of what John Grenier calls, “The First Way of War,” or a small war of annihilation. As Charles Lynn would explain it, this is an inescapable cultural baggage that permeated American society and provided a foundation for what Russel Weigley termed, “The American Way of War..” Even when America “modernized” its military in the early 19th century, that first way of war remained prevalent though, “limited” as Mark Kneely puts it. These limitations are very much the re-implementation of the 18th century’s “enlightened way of war.” Although the extreme level of Napoleonic total war was known to the U.S. and other countries that read Jomini at the outbreak of the Civil War, they did not practice it. Societal limitations checked the “total” aspects of war. I think that is why many Americans do not envision the Civil War as being “atrocious.” They see, as many in society believed it might be, “limited” in the sense of how wars were fought. This grandiose vision of Verdun’s mathematical lines across open fields depicts a scientific way of war fought by “gentlemen,” or in the case of the many countries, a military aristocracy replacing the 18th century’s birth aristocracy. The reality is that that the American geography pushed commanders to move beyond Jominian interpretations of grand strategy, technology created opportunities for revolutionary tactics and guerrilla campaigns, already known from the “first way of war,” reared their head.

In terms of violence on man, the Civil War is unique in that it represented the quintessential brother vs brother type of warfare. In such conflicts in the past, rules and regulations maintained a status quo on the battlefield. These types of warrior codes were quickly abandoned when fighting against the “Barbarian.” I think this plays into the question of race Kevin. Barbarians can be “othered” and therefore, their destruction is conceivable. The brother vs brother atrocities are harder to swallow. However, we also need to remember that this is not the first time “Americans” engaged in such behaviors. It existed against loyalists in the Revolution, and again in the war of 1812. In both cases, these were white against white. So what drives Americans, North and South, towards these atrocities? Personally I think Wayne Lee has a point in the book I referenced above. American warfare shows a preference towards violence due to its creation. The defining method of war for America, for over a century, were wars against natives, or Barbarian vs Barbarian. This is a method that Americans knew worked. When two armies come into conflict, the manner of violence is susceptible to increase. This can be because of cultural conflict or even a misunderstanding of how each culture wages a war. Lee states it best:

After the revolution, Americans convinced themselves of the virtuousness of their conduct compared to the rapacity of their enemies, and they entered the American Civil War expecting to wage another virtuously restrained war. Instead, the intensity of popular emotion, combined with the capabilities of the industrial era, convinced Union generals that this war required a return to strategies of devastation [Sherman’s March] previously reserved for Indians and Irishmen – although with much greater control over the level of violence.

To answer, how can ever really understand the men that fought there without understanding what impacts the way they fight, and what impacts the instruction of those that taught them to fight (both conventional and unconventional). To void this understanding leaves soldiers on a pedestal, or simply and wrongly equates them to a mine collapse survivor.

Thanks for taking the time to write such a thoughtful response. You make a number of good points. I am not so interested in taking anyone off their pedestal as much as I want to come to terms with a more inclusive and honest picture of what took place on those battlefields. I do believe that educators and public historians have a responsibility to push back against a narrative that reduces the Civil War to a “great adventure.”

Whether the Civil War was a total war or not is not as interesting to me compared to the overwhelming evidence that soldiers on both sides understood when they were moving beyond what they believed to be acceptable warfare or something un-Christian. I agree that these stories are more easily embraced when they involve “others” but that to me is an argument to push forward to explore examples of atrocities and other excessive forms of behavior throughout the war as opposed to leaving it on the fringes in both place and time.

To your point about the Revolution, I remember reading about the level of violence between Americans in the South in Ronald Hoffman’s class at the University of Maryland. It took some time to fully integrate these stories in my own limited understanding of the war and what I assumed were stable battle lines.

This is the first time I’ve heard of “No Quarter!” happening on the 1st Bull Run battlefield. This makes me think of that scene in Gods & Generals when Jackson tells JEB Stuart before that battle that if it were up to him, he would take no prisoners. Later, in the film, he says the only way to deal with invading Yankees (after Fredericksburg) is to “kill every last man of them.” I don’t know how accurate those scenes were but it sounds like some soldiers took it to heart at some point.

I think we have romanticized Civil War soldiers so much with the noble “brother against brother,” “Blue & Gray,” “North & South” symbolism so much that the brutality of that war gets overlooked too easily. The Civil War gets turned into this “sabres and roses” lovefest. Billy Yank and Johnny Reb weren’t really mad at each other… but they were thrown into a tragic circumstance that they had to go through. And after the war, they embraced across the stone wall and made up as if it never happened. Kind of hard to see brutality and the murder of unarmed soldiers through that.

Jackson lobbied for the black flag in May 1861, August 1862, and September 1862. “I have always thought that we ought to meet the Federal invaders on the outer verge of just right and defence, and raise at once the black flag.” There is evidence that he applied this approach during his 1862 Valley Campaign at Front Royal and Winchester.

A lot depends of which part of the Civil War you are discussing. In Missouri and Arkansas, it was anarchy.

However, I keep thinking that the current trend on emphasizing the savagery of war is skewed by something that affects, sometimes unknowingly, all modern views of war, the great purposeless carnage of World War I that left a continent devastated and very few if any European nations anything like what they were before.

Should we glorify war, which was often done in the 19th century? No, one only needs to look at the illusions, soon shattered, with which Civil War soldiers volunteered for duty at the beginning of the war. But I think we have to ask WHY focus on the savagery of war. Is the desired result to say that war is NEVER justified? I think the slaves of America and the occupied and oppressed under Nazi and Japanese rule in World War II might answer differently.

I think the current framework CAN accommodate issues both of the irreducible savagery of war and of atrocities when placed in context. Yes, it’s going to have to be adjusted by terms of the battlefield. Gettysburg was actually one of the last of the more formal battles in the Eastern theater. There’s material you need to get in there as an overview simply because it’s a gateway battlefield but you can also deal with the differences between Gettysburg and the Overland Campaign which involved the same armies and many of the same generals but which were radically different in all aspects.

Hi Margaret,

No disagreement re: the situation in places like Missouri and Arkansas. I would say we should talk about the savagery to educate a nation of the costs of war in all its forms. Americans should understand what it means when we decide to send young men and women into harms way. I am struck by how disengaged from war this nation has been over the past ten years and yet we have some of the highest suicide rates in the military.

I also believe that the present framework can accommodate these stories.

Kevin-Did you ever see the original Star Trek series episode “A Taste of Armaggedon”? I found an excellent column that ties it into our current state of having a prolonged war to which most of the population seems oblivious. “Neat, Painless, Perpetual War” by Michael Tennant http://original.antiwar.com/mike-tennant/2010/02/02/neat-painless-perpetual-war/. It includes a synopsis of the episode, which involves two planets conducting a virtual war by computer with casualties being assigned and reporting to disintegration chambers. The Enterprise visitors are appalled at the amorality of it and William Shatner has a great Captain Kirk soliloquy where he tells the leader of one of the planets’ high council, “”Death, destruction, disease, horror: that’s what war is all about, Anan. That’s what makes it a thing to be avoided. But you’ve made it neat and painless – so neat and painless you’ve had no reason to stop it, and you’ve had it for 500 years. Since it seems to be the only way I can save my crew [declared dead by the war computer and slated for annihilation] and my ship,

I’m going to end it for you – one way or another.”” He destroyed the war computers and the planets chose peace rather than annihilation. However, what we’re dealing with is not the radical choice of this episode. It’s more like the story of how to get a frog to cooperate with getting boiled to death. You don’t throw it in boiling water from which it will try to escape. You put it in at a comfortable temperature and then turn up the heat gradually.

One comparison that I heard John Latschar use in many of his talks is reminding people that, if the same percentage of soldiers killed in the Civil War were killed in a modern war, we would be looking at a death toll in the millions. (latest estimates are between 650,000 to 750,000 Civil War dead translating to 6.5 million to 7.5 million dead if the same percentage were to be KIA today.). I think the framework can and should discuss the impact on society of this loss. This was not an era that had much in the way of social safety nets, except for private charity, and with the death or disability of a man in a very patriarchal society this means a lot of widows, orphans, and parent(s) who the soldier had been supporting left penniless. Society struggled to deal with that after the war.

Re: Star Trek and the Civil War.

Great episode and I advocate using Captain Kirk soliloquies in most history lessons. 🙂

Are we to forget the atrocities committed against former (supposedly freed) slaves who were starved and murdered at the hands of Union soldiers?

What examples did you have in mind here? I understand that your response is more a reaction to an article focused on Confederate atrocities as opposed to any real interest in the murder of former slaves. Of course, I believe that atrocities committed throughout the war ought to be properly understood, including the violence that slaves and former slaves experienced at the hands of Union soldiers. One of the more interesting book out there now is Jim Downs’s Sick From Freedom (Oxford University Press), which examines the hardships experienced by slaves as a result of the sudden shift from slavery to freedom through war. You should check it out.

I’ve done a lot of reading on different wars and none of this is really surprising; atrocities happen on both sides and it’s no doubt happened since the beginning of warfare. The Civil War is no different so none of this surprises me as war is a bloody business. For example, on the Eastern Front during WW II, it was a war of extermination: no quarter asked, no quarter given. Although that doesn’t change the lofty goals for which the Civil War was fought or the struggles that place on the battlefield, it should be acknowledged, just as we should acknowledge the dark side of our history, e.g. the destruction of Native Americans and Jim Crow South.

Thanks for the comment. Sure, but the question is whether our current framework for understanding the Civil War battlefield and the war as a whole can accommodate such stories.

I’m guessing that you don’t think it can because of the idealized view we have of the long struggle to free four million people from bondage?

Within the existing framework, we have to fit into the notion that war is a dirty business and that in the course of achieving the ultimate goal, things take place that you wish had not taken place. I don’t believe anyone thinks less of the liberation of Western Europe because of some of the things that took place.

Don’t know if I’ve answered your point.

Hi Brad,

It’s not so much related to the issue of emancipation as much as it is to acknowledge the level of violence in our civil war. We have little difficulty coming to terms with civil wars elsewhere, say in Iraq or Bosnia, but we tend to close our eyes in this case. Perhaps it has something to do with our commitment to an American Exceptionalism that assumes we are different in kind from everyone else. I don’t know.

Kevin,

I think it has something to do with that but also with the belief that, at least from the Union side, we were on a noble mission and that therefore to admit of atrocities detracts from that view.

As I think about it more, the way we perceive things doesn’t currently admit of that possibility (as you suggested) so maybe Pete Carmichael is right that we need to also focus on the “war is hell” view.

Brad

Perhaps, but you are going to need to make the case for such a view.

“…with the belief that, at least from the Union side, we were on a noble mission…”

Many Americans did believe that they were on a noble mission to save the Union. That is not something that we need to revise; in fact, it seems to me we want to emphasize it as much as possible if we are to understand the war and its outcome.

I think you both need to check out <a href="http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/HistoryOther/MilitaryHistory/?view=usa&ci=9780199737918" Barbarians and Brothers

Anglo-American Warfare, 1500-1865 by Wayne E. Lee You guys are hitting on a lot of his arguments.

Oops, blotched hyperlink. My bad.

What I was trying to say that if the view (presently) is that the North was on a noble mission, anything that shows the warriors as less than pristine doesn’t fit in with the “story” and shows them to have feet of clay, if that makes any sense.

It makes absolute sense and I tend to agree with you. The question is how can we make sense of their claim to be engaged in a noble mission and be honest to the historical record even when it conflicts with our assumptions.

Excuse me, but detention without trial is not a war crime. Can you give examples of Union forces killing prisoners or unarmed civilians, causing the deaths of POWs by ill-treatment? I would guess it must have happened sometimes, but were the great majority of such crimes committed by Confederates, or not?

While there is massive room for debate on the actual suspension of habeas corpus, both the US Constitution provides (and the Confederate Constitution provided) for the suspension of the Great Writ as Article I, Section 9 of the US Constitution states, “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The issue, in ex parte Merryman, was whether the President could suspend the Great Writ at time of national peril when there was no Congress in session. The situation at the time of the initial suspension, when Congress was not in session, was not a matter of going after dissenting newspaper editors. Secessionists were burning bridges and cutting railway lines and Union volunteers who were changing trains in Baltimore on their way to defend the US Capitol were attacked by a Baltimore mob. If people think this was harsh on the US government’s part, compare it to the Confederate suppression of Unionists in East Tennessee, that produced this communique from Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin:

>>WAR DEPARTMENT, C. S. A.

Richmond, November 25, 1861.

Col. W. B. WOOD, Knoxville, Tenn.

SIR: Your report of the 20th instant is received and I proceed to give you the desired instructions in relation to the prisoners taken by you amongst the traitors in East Tennessee:

First. All such as can be identified as having been engaged in bridge-burning are to be tried summarily by drum-head court-martial and if found guilty executed on the spot by hanging. It would be well to leave their bodies hanging in the vicinity of the burned bridges.

Second. All such as have not been so engaged are to be treated as prisoners of war and sent with an armed guard to Tuscaloosa, Ala., there to be kept imprisoned at the depot selected by the Government for prisoners of war. Wherever you can discover that arms are concealed by these traitors you will send out detachments, search for and seize the arms. In no case is one of the men known to have been up in arms against the Government to be released on any pledge or oath of allegiance. The time for such measures is past. They are all to be held as prisoners of war and held in jail till the end of the war. Such as come in voluntarily, take the oath of allegiance and surrender their arms are alone to be treated with leniency.

Your vigilant execution of these orders is earnestly urged by the Government.

Your obedient servant,

J.P. BENJAMIN,

Secretary of War.

P. S.–Judge [David T.] Patterson, Col. [Samuel] Pickens and other ringleaders of the same class must be sent at once to Tuscaloosa to jail as prisoners of war.

J.P. B.

[NOTE.–The same letter with a slight verbal alteration of the opening paragraph and the omission of the postscript was sent at the same time to Brig. Gen. F. K. Zollicoffer, Jacksborough, Tenn.; Brig. Gen. W. H. Carroll, Chattanooga, Tenn., and Colonel Leadbetter, Jonesborough, Tenn.]

—–

RICHMOND, December 10, 1861.

General W. H. CARROLL, Knoxville:

Execute the sentence of your court-martial on the bridge burners. The law does not require any approval by the President, but he entirely approves my order to hang every bridge-burner you can catch and convict.

J. P. BENJAMIN,

Secretary of War.<<

Democracies/Republics do not tend to deal well with civil liberties in time of war, especially civil wars where it becomes next to impossible to tell friend from foe and the line between lawful, loyal dissent and aid/comfort to the enemy becomes dangerously blurred. I recommend Mark Neely's books "The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties" and (after he, by chance, discovered the records of the Confederate Habeas Corpus commissioners in the unrelated files of the Confederate Secretaries of War) "Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism"

Democracies/Republics do not tend to deal well with civil liberties in time of war, especially civil wars where it becomes next to impossible to tell friend from foe and the line between lawful, loyal dissent and aid/comfort to the enemy becomes dangerously blurred.

What a hoot. Abraham Lincoln knew full well who owned the printing presses he was destroying.

You said: “Only a minor few slaves were mistreated by their Southern owners. The maltreatment of slaves was perpetrated by the Yankee and English slave traders. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson actually had slaves on the auction block beg to be bought by him, because Jackson treated his slaves so well. Social Security and welfare and food stamps were not necessary either. No slave was impoverished and their owners took very good care of the slave until they died of old age.”

Terry,

Are you that guy Scott Terry who recently made news for defending slavery as giving Black people “food and shelter” at a recent Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) conference in Maryland? In any case, I know there are people who look back on slavery in the United States as if it were some sort of benefit to African-Americans. Personally, I could care less whether or not it happened North, South, East or West… I don’t see were it was a “benefit” to Blacks anywhere.

My personal opinion is if you’re a Southerner and you have Confederate, slaveholding ancestors or you’re just somebody who admires the Confederacy, I have no problem with that. But what I hope you would do is come to terms with the world that they wanted: one of permanent White supremacy over Black inferiority. All kinds of White people were a part of that world; from evil, sadistic, brutal slaveholders to professing Christians. And being a historian is attempting to understand why they did what they did.

Trying to minimize the past and pretend it didn’t happen or trying to shift all of the blame on other people just makes you arguments sound so ridiculous. Your ancestors deserve better than that.

Keegan’s The Face of Battle is a good source for soldiers in combat. He discusses how in the heat of battle it is sometimes not possible for a defeated soldier to have his surrender accepted.

Bennett mentions this as well. Thanks.

I would also recommend Charles Lynn’ “Battle.” It is less of a Western Exceptionalist approach. Lynn creates a great look at how culture affects the way humans wage wars on one another.

I am not familiar with it, so thanks.