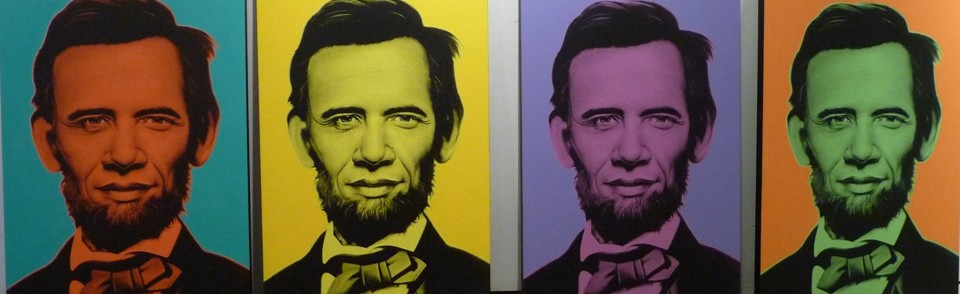

While running for the presidency in 2008 Barack Obama made it a point to align himself and his campaign with what he viewed as Lincoln’s vision for the nation. For many, Obama was the heir to Lincoln’s legacy. Those connections were only reinforced following his victory. In that moment the Civil War and even Reconstruction made perfect sense and it felt good. Artist Ron English’s painting and popular print, “Abraham Obama,” beautifully captures this collapse of historical time. Look closely and it’s difficult to discern where one ended and the other began.

The promise of a post-racial society has all but collapsed with recent news stories of the shooting deaths of young black men by police and the overwhelming evidence that racial inequality is growing wider in the United States. Many Americans are disappointed in what they perceive to be a lack of attention to matters of race by the president himself. But if Obama disappoints, Lincoln is always available to point us in the direction of “the better angels of our nature.” As we approach the 150th anniversary of his assassination echoes of Lincoln’s role as our national moral compass will likely grow louder. We would do well to be cautious.

This weekend Martha Hodes, who has authored a wonderful book on how Americans responded to Lincoln’s assassination, published an op-ed that considers the most famous lines from his Second Inaugural Address. She argues that in the shadow of recent cries for ‘Black Lives Matter’ we should reconsider Lincoln’s call: “with malice toward none, with charity toward all.”

Many at the time thought they knew what Lincoln meant, and many today understand those words in the same way: As the Union Army approached triumph, it seemed that Lincoln wanted the conquerors to treat their vanquished Confederates with mercy. But what if that reading misunderstands the fundamental political impulse behind those lyrical directives?

I believe that this indeed captures Lincoln’s “fundamental impulse.” It is true, as Hodes explains, that white and black Southerners embraced radically different visions of reconstruction and it is also true that Lincoln’s vague words about the possibility of a limited suffrage for some blacks sent John Wilkes Booth over the edge. In the wake of his assassination it is undeniable that black Americans mourned the loss of a president that for them held great promise.

Unfortunately, by placing Lincoln (intentionally or unintentionally) on one side of a mutually exclusive choice over America’s racial future, Hodes ignores a crucial element. The vast majority of the loyal citizenry of the North did not fight the war primarily to end slavery with the promise of civil rights. They fought and died to preserve the Union. Mark Summers makes this perfectly clear in his new book, The Ordeal of the Reunion: A New History of Reconstruction.

That desire to return to the way things had been went to the heart of white northerners’ ideal of “Reconstruction.” To reconstruct meant to build again, for some to build anew, but for many others to raise an edifice, with more solid foundations, perhaps, but a distinct resemblance to the structure that had stood before the war. The place of blacks in the new order of things must change, but the essence of a republic, federal and not consolidated, must not. Finally, there was a point to obvious that later generations could overlook it. The one indisputable aim of the war had been to bring the Union together again and, the issue of slavery aside, a Union recognizably like the one left behind, based on the consent of the governed and the widest possible latitude for state power and personal freedom consistent with rule of law and a supreme national authority. (p. 13)

This is the historical context in which we must understand Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. This is the context in which to understand what he meant by “a just and a lasting peace.” This is the ‘work that the nation must strive to finish.’ Hodes concludes:

Lincoln’s call … today holds a special poignancy — and a call to action. For as protesters in New York, Florida and Missouri remind us now, without justice, peace will remain elusive. As will Lincoln’s spirit of “malice toward none” and his guiding vision of “charity for all.”

In embracing his words as a rallying cry we betray a need to believe that had he the opportunity Lincoln would be standing alongside marchers in Ferguson and elsewhere. But what if imagining Lincoln throwing tear gas cans gets us closer to the hard truth and a better understanding of America’s racial problems?

I think that Gary Gallager’s “The Union War” is quite convinicing. Did most Northern soldiers fight to preserve the Union. Yes, but what did the language and idea of Union mean to them? “Liberty and Union”. I think that it was quite possible in the context of 19th Century America for a northerner to be uncomfortable with the instutution of slavery. Not because they believed in racial equality but because they saw slavery as supporting “oligarchy” or aristocracy. Which the Union was thought to undermine, the idea that unlike the old world of Europe that in America you could rise as far as your talents could take you. The Southern Confederacy was seen as a threat to the that belief.

Slavery supported a system that locked in the large plantation owners into purpetual posistions of power and small farmers as yeoman dependants. Many southerners fled the upper south and settled in southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois because they felt that there was simply more opprotunity than there was in the southern states. One of those men was Lincoln’s father. I think Lincoln was uncomfortable with the notion of slavery from early on. He probably also had many of the racist beliefs of his time and place. However I think he evolved on this issue overtime.

I agree strongly with what London John has to say – Lincoln and Pro-Slavery types both know that slavery must expand or die. This is rooted in the house of representitives. In order to keep politcal power, the slave power needs seats in the house. If the west becomes “free” then the slave oweners power will be diminished and eventually compromised.

Ok I have rambled enough – I have to thank Kevin for making me aware of Gallagers book. It was quite good.

Union and Abolition have been mentioned; maybe Free Soil should also be considered here? Northerners who disapproved of slavery but not enough to do anything about it were determined that the lands still to be taken from the Native Americans should be settled by free farmers and not slave plantations. So they supported Lincoln’s platform of restricting slavery to the existing slave states, which both Lincoln and the slaveholders understood would make slavery unprofitable in the long run. So the Confederacy was determined to expand slave agriculture westward, which surely made a lasting peaceful separation impossible? The Homestead Act can be seen as achieving a Union war aim.

/this is a little off-topic for this thread (although not for your blog),

/and I won’t be upset if you don’t let it through.

Kevin, In case you missed it (unlikely), I want to flag a lengthy NY Times article about the Whitney Plantation Museum in Louisiana, “built largely in secret and under decidedly unorthodox circumstances,” to become what Eric Loomis of LG&M aptly described as the country’s first “no punches pulled museum” on slavery. In the words of Yale Professor Holloway, it’s a “‘genius step’ in a long-overdue direction.” http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/01/magazine/building-the-first-slave-museum-in-america.html .

The Times author did an outstanding job. He profiles John Cummings, owner of the plantation, and tells the history of Cummings’ idea for and sponsorship of the museum project. The author also thoughtfully explores issues that are central to many of your posts on this blog, namely the ways in which “slavery [is] so difficult to think about” and the difficulties involved for the nation in determining how to publicly remember, understand, and tell the story of slavery, to commemorate (and sometimes mourn) our enslaved countrymen, and to understand the ongoing consequences of slavery’s 250 year history on our soil.

Why should the mythologizing continue unchallenged? Oh, and on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial are dozens of carefully selected quotes and passages without any context or explanation. You would agree those quotes and passages should be removed, right?

It’s a monument. So you now want to remove the inscriptions on every monument in Washington D.C and beyond?

The Lincoln Memorial has only two quotes: The Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, both in full. They are “carefully selected” only in that they are almost unanimously considered to be his greatest speeches.

Wrong. The Gettsyburg Address and the Second Inaugural are inscribed on the walls of the Chamber itself. The Plaza Level has additional exhibits and, as I correctly stated, dozens more quotes and passages. And they were all “carefully selected” precisely because they didn’t contain any racial slurs, advocate the colonization of African-Americans, or advance Lincoln’s white-supremacist views.

And they were all “carefully selected” precisely because they didn’t contain any racial slurs, advocate the colonization of African-Americans, or advance Lincoln’s white-supremacist views.

Lincoln’s views had evolved by 1865. He no longer subscribed to colonization and his final speech called for the vote for a limited number of black Americans. In other words, he had evolved drastically since the 1850s. As for the Lincoln Memorial you shouldn’t go if you don’t agree with the views expressed in those two speeches.

“As for the Lincoln Memorial you shouldn’t go if you don’t agree with the views expressed in those two speeches.”

Please tell me as a educator, you are not serious about that statement.

I am telling you as a citizen of this nation.

Your comments are taking this thread too far afield. Thanks for taking the time to read and share your thoughts. Good day.

Two of the greatest political speeches in US History, if not World History, and you reduce them to “quotes” and “passages”. No agreement on that. As with everything, you take the good and the bad. Lincoln’s good, far outweighs the bad, and Lincoln is one of those individuals who can hold two opposing thoughts in his head, wrestle with them, and come out with a changed perspective. His view on slaves at the end of the war was not the same at the end. It changed because of Douglas and the overwhelming joy and regard former slaves held in him (think of his walk thru Richmond — how could that not affect him?). He began as a Southern boy, and left a man of the World.

Correction: His view on slaves at the end of the war was not the same as the beginning.

Owing to the mythic and hagiographic characterization of Abraham Lincoln, Americans in 2015 have a wildly distorted and hopelessly superficial understanding of both the man and the politician. And consistent with his hagiography, Lincoln is persistently presented as kind, decent, avuncular, pacific, magnanimous, and benevolent. His hagiographers cannot but help to somehow fit in the quote “the better angels of our nature” at every opportunity. The historical truth is very different. That history records a Lincoln who was pragmatic, shrewd, cold, calculating, cruel, brutal, avaricious, and racist. If we really want to advance and promote a deeper understanding of Lincoln, we could, for example, start by adding a few of his more colorful quotes to the walls of the Lincoln Memorial:

“There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races … A separation of the races is the only perfect preventive of amalgamation, but as an immediate separation is impossible, the next best thing is to keep them apart where they are not already together. If white and black people never get together in Kansas, they will never mix blood in Kansas …

and

“but “where there is a will there is a way,” and what colonization needs most is a hearty will. Will springs from the two elements of moral sense and self-interest. Let us be brought to believe it is morally right, and, at the same time, favorable to, or, at least, not against, our interest, to transfer the African to his native clime, and we shall find a way to do it, however great the task may be.”

and

“I have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

and

“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races. There is physical difference between the two which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position.”

and

“We profess to have no taste for running and catching niggers,”

As we approach the sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s death, and if we want an honest and open dialogue which engenders a more complete understanding of Lincoln, and one which capture his “fundamental impulse, we must fully confront the ugly truths surrounding him. Lincoln was a committed racist and passionate white-supremacist, but he undoubtedly believed that black lives matter. It’s just that he also believed white lives matter more. That fact needs to be acknowledged, not suppressed.

So, after accusing everyone else of falling prey to a mythologized Lincoln you go ahead and select quotations without any context/explanation that you believe offers an accurate picture of Lincoln’s life. This is worse than mythologizing.

Not to mention quotes that can be countered by and should be considered in context with other things Lincoln said and wrote as he changed his mind.

Kevin Levin is correct in countering Conrad’s statements by pointing out his comments are “worse than mythologizing”.

I’m going to try to align the Stars here, just a little bit…so bare with me. (Mostly this was a copy and paste from something much larger I was working on some time ago. Yes some typos and citations missing but can easily be followed up on with basic research for those that care).

Some modern historians hell-bent on claiming they’re addressing the *whitewashing of* “Lincoln the great emancipator” to “set the record straight”… are often just as far off as those that think otherwise. So, they go the other way with it and try to prove him to be a ‘shrewd, racist”.

Part of the problem is it requires much more research than even those that claim to be *well-researched* realize before we have a thorough knowledge and understanding.

Keep in mind, anyone living today trying to associate their own reality to a person, and the events of their times, is interpreting that history from the future (our modern era), and in doing so, if the historic person in question isn’t studied thoroughly, a great injustice is done. After all, who really wants to pride themself on talking points that take away the humanity from another human being, if there’s a chance they could be wrong?

Most people that scribe to be telling the “truth” and pointing out how Lincoln was just another racist and/or white supremacist of his day are always very good at cherry-picking the same three or four things, while ignoring the literal dozens of other things that would suggest he was otherwise.

When it comes to discussing historical individuals it first requires in-depth study of their person, including going as far back as possible … their childhood if possible … to understand their moral code, character, Etc.

People like Conrad just hate stuff like this below (what I’m about to submit) … the things that are “truth” and give Lincoln some of his humanity back . Peculiar to me that these things are so well documented yet conveniently, often ignored.

One thing we know about Lincoln in his youth, as interviews taken from folks that knew him on the frontier, are all consistent describing a peculiar boy, different from others, that had a higher than normal empathy expressed towards people AND animals.

This “empathetic” adjective seems to be a consistent adjective used to describe him by an overwhelming number of those interviewed that knew him throughout his life.

There is No Way that it’s just an accident that people that knew him before he was famous, as well as exslaves and abolitionist (both white and black), used the same adjective in describing him throughout the years, if there wasn’t truth to it.

When still a young man, in the Black Hawk War, William Green tells the detailed story about how when a scared Indian wandered into their Camp during the war, all the men in their company took on a Lynch Mob attitude, wanting to harm, kill the Indian.

Green explained it was Lincoln who stepped forward to save the Indian. He said it was a remarkable moment for him personally because it was the first time in his life he witnessed such bravery or humanity from another man willing to risk his own life to save another. He pointed out the hostility among Lincoln’s fellow soldiers was so high that Lincoln physically put himself between the Indian and his fellow soldiers, telling them they would have to kill him before he would let them get to the Indian.

This is a remarkable anecdote, albeit only one of many others, that shows us something that proves the character and integrity make up Lincoln seemed to always have.

Long before the world (and history) would know him as President Lincoln, he showed an often rare humanity by doing things that showed an unquestionable internal passion for justice.

Let’s be honest, how many of us in our lives have ever stood between another human and an aggressive mob, trying to be the voice of reason?

Can any of Lincoln’s critics over the years, quick to dismiss him as just some shrewd, cold-hearted individual, claim that they have ever done such a thing?

One of his earliest first known speeches when in his late 20’s he publicly addressed the inhumanity of slavery.

Viewed through *presentism* (the viewing of History through the modern lens) this doesn’t seem like such a big deal, but those that have context and know the times realize that although that doesn’t make him an abolitionist it was still a radical stance… and the documented writings from those with an opposing view at that time often described Lincoln as a radical.

Lincoln addressing the injustice of slavery on many different fronts in public speeches and in personal letters to friends. This a consistent pattern over the remaining decades of his life, so much so that those of his era described him as a progressive minded person, even if not an extremist or abolitionist.

Many that wrote about him during his presidency, especially in the South referred to him as “a friend to the Negroes” and “a threat to abolishing slavery”.

And it’s ludicrous that people in the modern era (2016) think they have a better spin on Lincoln then those from his actual era.

As years went on, abolitionist extremists that at one point were critical of Lincoln’s “appearance to be indifferent to aggressively putting an end to slavery”, they admitted after the dust settled they realized his consistency and his character proved he was indeed always goal oriented towards seeing an end toward slavery. .. and on moral grounds, not political.

Many of them (Kady Elizabeth Staunton and Harriet Tubman, to name only two among many) admitted they were harsh in their judgment of Lincoln, for they came to realize he always remained consistent in his loathing of the inhumanities and injustice of slavery and wanting to see an end, but was also in precarious position of trying to keep our country from permanently dividing over the issue. Hence he also had to play politician.

Many abolitionists extremists point out as the war went on that they started to see Lincoln’s patience as genius because they recognized what HE already knew, which was that had he (or for that matter any other politician) came out in 1961 as president and announced “an immediate end to slavery” there would have been no saving of the Union, and slavery would have been ongoing for much much longer…. AND the president, whoever they would have been, would have been assassinated almost immediately.

Intense scrutinized research bares this to be absolutely true. There are over (well over) 500 writings from people of Lincoln’s era, both from the North and South perspective, that make this clear.

Even on Colonization, we almost always are guilty of viewing this through the lens of modern times with very little context, many historians, educators and professors of this history are guilty of this.

It is usually sloppily told to mean Lincoln just woke up one day saying he “wanted all blacks rounded up and shipped out of America” to imply *he didn’t like blacks and didn’t want them here*.

But, again for those that have context and historical knowledge of the times we know this was NOT such a radical view against black people at that time.

The whole reason Lincoln considered colonization in the first place was because some other countries were doing it and those black folks colonized were expressing it to be a good thing.

This is not white spin. This is actually documented from black activists of those days, and in fact it was many black activists that were in favor of colonization themselves, which is why some of Lincoln’s cabinet members and Lincoln gave it serious consideration to begin with.

He was very clear on this issue, and his viewpoint was very similar to black activist leaders like Frederick Douglass, knowing full well the racist climate of white America, Lincoln (as Douglass and many others) felt the only chance for the black community to experience an existence in the near future that afforded them a life free of oppression and racism from others was to be somewhere where there were no whites.

Lincoln’s feelings, in essence were, as many other black activists felt the same, a somewhat slight or slap at White America’s inability and unwilling interest in getting along with their darker skin citizens.

Keep in mind when Attorney General Bates, and many other white leaders recommended that blacks be “rounded up and expelled” , Lincoln “objected unequivocally to compulsion” insisting that their “emigration must be voluntary and without expense to themselves”.

Wells diary entry for September 26th, 1862.

He was very clear on numerous occasions that it was not his desire to force blacks to leave and if done it was done in their own interest and of their own will.

Once some time went on and they could see it was difficult to successfully colonize, Lincoln, along with many of the black leaders that supported colonization, all scrapped the idea before the war ended.

As the war went on Lincoln became more and more able to tip his hand and start to publicly make decisions and say things that many black activist and white abolitionists said rendered him in the heart of John Brown, or many other extremist abolitionists. Again, not spin, documented words from those of Lincoln’s time.

One of Frederick Douglass last meetings with Lincoln almost brought him to tears as Lincoln, prior to Lincoln’s second inauguration, he spent over two hours with Lincoln, while many other white people were waiting to speak with him.

Douglass was moved by Lincoln making it clear he did not want to be interrupted while he was spending time with his old friend… Frederick Douglass. Douglass explained (as other black men and women that spent time with Lincoln) this type of *favored, genuinely respectful behavior* “towards” a black person, coming from a white man of power, was extremely rare if not unheard of.

He said Lincoln had put together an aggressive plan that only an abolitionist at heart would think of.

Lincoln wanted Frederick Douglass thoughts on going about putting together a strategic idea or militia to penetrate the deepest parts of the South where slaves were still not set free and being tortured.

It was in that moment that Frederick Douglass expressed that even though he had felt earlier on Lincoln was passive, possibly even seemed indifferent to slavery, he then realized and knew Lincoln had been the right man to be in that position all along. For only a man who had justice and empathy in his heart for what Douglass’ fellow black people were going through would be capable of thinking of such a plan.

People that want to view Lincoln has a cold, racist tyrant, are either ignorant of these things, or they conveniently, suspiciously ignore them.

While it’s true these things are very complex, but it’s also fair to say that people that try to deny these things are bordering on plain ole SILLINESS.

I say that simply because this is not secret, hidden information. It’s all well-documented and has all been around for the same amount of time as some people have been trying (suspiciously) to deny these things… usually due to a sad, twisted agenda to turn Lincoln into some sort of tyrant.

And the lesson here or my message would be that it requires not only your honesty but true humility in researching and discussing famous people of the past.

I NEVER, EVER, trust the viewpoint or writings from a modern historian. Some well-intentioned, others just have an agenda. But I highly recommend that people quit telling each other which books to read, unless they have first started with books that are well cited quotes and writings from the people of Lincoln’s era.

Far too many people discuss this history, without ever having done this, so the cycle of ignorance continues.

Who do we think would be better equipped to give a clear view of you or I in 2016? hundreds of people interviewed right now in 2016 that no each one of us personally… or people 150 years from now that each cherry pick random, separate details of our lives and then put their own spin on 2016?

Come on now, people need to keep this in mind when discussing historical figures.

Lincoln wasn’t perfect, but then again are any of us? Trust those that were there. Don’t trust those that were not, yet twist the words of those that were there.

Thanks for this thoughtful post, Kevin Levin. Interestingly, the editors at the LA Times bestowed the title on my op-ed piece at press time, without consulting me. Not that I would have objected: I like the title very much–but just to say that I did not write the essay around that idea. Reading the piece with the editors’ title, it makes sense to me, metaphorically, if not literarly–and perhaps we must always speak metaphorically when writing across centuries. And yes, most white northerners fought for the Union, but Lincoln was also deeply influenced by black and white abolitionists over time. Moreover, as James Oakes tells us in *Freedom National,* he and the Republican Party were intent on ending slavery from the very start of the war.

Hi Martha,

Thanks so much for the response. Oakes’s certainly offers a provocative thesis, but I was responding more to what I thought you were claiming about Lincoln’s Second Inaugural – that Americans have ‘misunderstood the fundamental political impulse’ behind his words. As I suggested I think we should resist interpreting Lincoln’s words outside of an 1865 context, though I completely agree with you that his words do speak to us in powerful ways.

Thank you for the thought provoking post. As I am reading “Rebel Yell” by S. C. Gwynne my question is why war? Why dismiss the peace negotiations and choose war? Slavery caused conflicts in some countries but only in America did we resort to war and the loss of 750,000 lives. Slavery was not only a horrible institution, it was a terrible business model that could not be sustained through the industrial revolution. Was past and current racial strife in America caused by the ‘share cropper’ model of cheap labor? Did the current racial unrest have its Antebellum beginnings when slaveholders pitted black slaves against white slaves as a control measure? Are the West Indies less troubled because white slaves outnumbered the black? As I said, very thought provoking.

Glad you enjoyed it. Most Northerners who volunteered in the first half of the war did so to save the Union. That concept may not mean much to Americans today, but it did in 1861. Again, I recommend Russel McClintock’s book, Lincoln and the Decision For War.

Slavery was not only a horrible institution, it was a terrible business model that could not be sustained through the industrial revolution.

This is simply not the case. Slavery helped to create the Industrial Revolution. Two recent books that are worth reading on this specific issue: The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward Baptist and Sven Beckert’s Cotton.

I’ve read McClintock’s book and time permitting I’ll read your recommendations.

In your opinion do you feel that the war was justified considering the lives lost and continuing misery in the south? Label me Chamberlain, but it seems to me that appeasement and negotiations would be in order to avoid war at all cost.

I don’t know how to answer that question apart from admitting that I am glad that the Union was not dissolved and that slavery was abolished from the North American continent for good.

I’m continually perplexed as to why there is an impulse in this post and in much of what I have read about the Civil War during the sesquicentennial commemoration to set “the issue of slavery aside” and to declare that “the vast majority of the loyal citizenry of the North did not fight the war primarily to end slavery with the promise of civil rights.”

Firstly, I do not think one can set “the issue of slavery aside” during any discussion about the Civil War. Why do we want to anyway? Do we think in doing so we’ll get to the “true heart of the matter”? Plain and simple, slavery is the true heart of the matter. We don’t have to set it aside to discuss other contributing factors. Yet time and again I see this “setting aside” in articles, blogs, and history books. I truly don’t understand why. Any thoughts?

Secondly, why do we feel the need to point out time and time again that “the vast majority…of the North did not fight primarily to end slavery…”? Soldiers don’t set political objectives. Their motives for enlisting (which are no doubt very complex) have no bearing on why or how the war is waged. We do not poll our 20th & 21st century soldiers and ask them if they agree with the political reasons for the war they’re engaged in. We understand that is a separate thing entirely. Why do we feel differently about Civil War soldiers? Any ideas?

Thirdly, President Lincoln. Was he perfect? No. Was he pragmatic? Yes. Was he a political genius? Yes. Was he consistent in his political ideology? For the most part, yes. Yet, we want to focus time and time again on his inconsistencies and look past the forest for a few trees. Why? Why do we want to consider the possibility that Lincoln would be throwing tear gas at the protesters of Ferguson rather than standing with them (I don’t understand why it has to be either/or)? Does “imagining Lincoln throwing tear gas cans” lessen our opinion of Lincoln or raise our opinion of the police (or both or neither)? Like I stated at the outset, I’m perplexed.

Your blog is about memory – about how we remember and/or think about the Civil War. Maybe asking why we remember the Civil War in certain ways and why we continually frame it in certain ways is beyond the scope of your blog but you sure do have me wondering.

Thanks as always for your excellent posts.

Patricia Kitto

Hi Patricia. Thanks for the comment. No one is trying to push aside slavery. Many Americans celebrated the end of slavery. My concern is that we too easily fail to draw a clear distinction between the abolition of slavery and civil rights.

It is set aside because it is too hard. One of America’s original sins (the other being against the 500 Nations) is not something America has even wanted to examine or correct. Equitable treatment in education, justice, the market, and society would go a long way to solving this. Ferguson, I Can’t Breath, even the pushback on AP History are how far our heads are still stuck in the sand. Its getting better, but there is still a long way to go.

“The vast majority of the loyal citizenry of the North did not fight the war primarily to end slavery with the promise of civil rights.”

I don’t think this distinction is that clear cut. The impression I’ve got, not ;least from this blog, is that of course the loyal citizens went to war to save the Union; but as the war went on they adopted the attitude, to simplify grossly, “the slaveholders have tried to destroy our nation; therefore we will destroy slavery”. I can’t really imagine their not feeling like that. How far hatred of the slaveholders extended towards sympathy for the slaves is more difficult.

Agreed. The destruction of slavery would strengthen the Union.

I’ve lately been thinking that we can go further with this line of thought. It seems unexceptional to accept that “union” rather than “freedom and civil rights” was the predominant motivation at the start of the war. But it was more than “union” as a general concept. Even at the start of the war, the Union that the Northern soldiers fought to save was one that had just put into power a party opposed not just to the expansion of slavery but to slavery in general, as described persuasively by Professor Oates in “Freedom National” and “Scorpion’s Tail.” See Brooks Simpson’s January 17 post on the ways in which the Republicans’ antislavery strategies went beyond the limits of direct congressional action that would have been subject to the Corwin Amendment. https://cwcrossroads.wordpress.com/2015/01/17/why-worry-about-lincolns-election/

That doesn’t of course mean that we can ascribe to most or even many of the northern troops the anti-slavery views of the Republican party. Many northern soldiers would have preferred a Democratic administration devoted to protecting the ability of the southern states to continue their slave economy within the union.

But I think we can say that the northern soldiers knew and accepted that their efforts to save the union under Republican leadership would also have the effect of advancing to some extent the Republicans’ policy with respect to the future of slavery, modest and uncertain as the strategies to implement that policy might have been in 1860 and early 1861. In other words the citizens who enlisted certainly didn’t find the Republicans’ antislave policies sufficiently abhorrent to destroy their willingness to fight under Republican leadership.

Good points. First, I am not suggesting that we can draw a sharp line between slavery and Union during the war. No doubt, the calls for Union were most pronounced at the beginning of the war, but as it progressed it is clear that more and more people understood that the end of slavery would strengthen a reunited nation.

To your larger point, I think it is important to keep in mind that Lincoln barely won 40% of the popular vote in the Northern states. In many counties he barely won. We should be careful to ascribe pro-Republican views to the men who answered Lincoln’s call in 1861. Jonathan White also argues that we need to be careful to assume that the soldiers vote in 1864 was a vindication of Republican policies.

You make a point indirectly which is worth thinking about. If, as you say, the people who fought for the Union literally fought for the concept of union why was that? If you lived in Massachusetts in 1861 and the southern states went their own way, what was the practical impact in your life? There might have been some economic impacts, but for the most part your life would have continued as it was. So why fight? And more to the point, what was there in the character of these people they would fight essentially for an idea?

I would suggest the Constitution, and how they interpretted it, mattered to these people in a way it doesn’t matter to us today. And the recency of the Revolution (people had near relatives who they had heard directly speak of that period from experience) likely factored in. Finally, I think fairness requires we consider that sectionalism existed to such an extent that real deep seated resentments and anger player a part on both sides.

If secession occurred today would people react the same way, supposing it required them personally to join the military and defend the Union? It’s an interesting question because I believe the volunteer army has made it too easy to commit armed forces because not all of society bears the toll of war. In any case, this post will put me back to reading more about the coming to war, which is something I’ve not done enough of.

Start with Russell McClintock’s Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession (UNC Press, 2008).

Why, independently of slavery, should northerners support the war to destroy the CSA and to restore US supremacy over the territory claimed by it? A little thinking and looking at a map will provide suggestions. First, an independent CSA might ally with Britain, evoking a threat as a friend once put it to “end the dream of manifest destiny.” Secondly, an independent CSA might use the lower Mississippi as a threatened choke point in negotiations for a division of the western territories. Third, an independent CSA might scheme endlessly to promote further secessions, as the CSA was actually doing before Fort Sumter. Fourth, an independent CSA would be a competent military power, and would certainly raise defense costs for the US. Many rich Americans had traveled in Europe and had seen the costly defense forces supported there. Young Henry Adams suggested in a letter that it would be cheaper in the long run to destroy the CSA than to live with its threats. Surely the men who held high office could see these dangers in an independent CSA.

I agree these are all good reasons the government might have wanted to prevent secession but I don’t think the average citizen was thinking in those terms. But, I could be wrong and it’s an interesting topic to follow up on. On a related note, some Confederates, chief among them Beauregard, felt that making a greater effort in the western theater could threaten the Mississippi and cause Western Pennsylvania and Ohio to split from the Union (not joining the Confederacy, just splitting the western part of the Union away). Sounds farfetched, and no doubt was, but the fact it was discussed at all makes for interesting reading.

Better be careful. You are talking way too much about “inequality” and not nearly enough about “American exceptionalism.” Those commies at the College Board might try to recruit you.

All jokes aside, I love your last line about Lincoln throwing tear gas. His political pragmatism cannot be overlooked.

All jokes aside, I love your last line about Lincoln throwing tear gas. His political pragmatism cannot be overlooked.

I chose those words carefully by leaving its meaning open to interpretation.