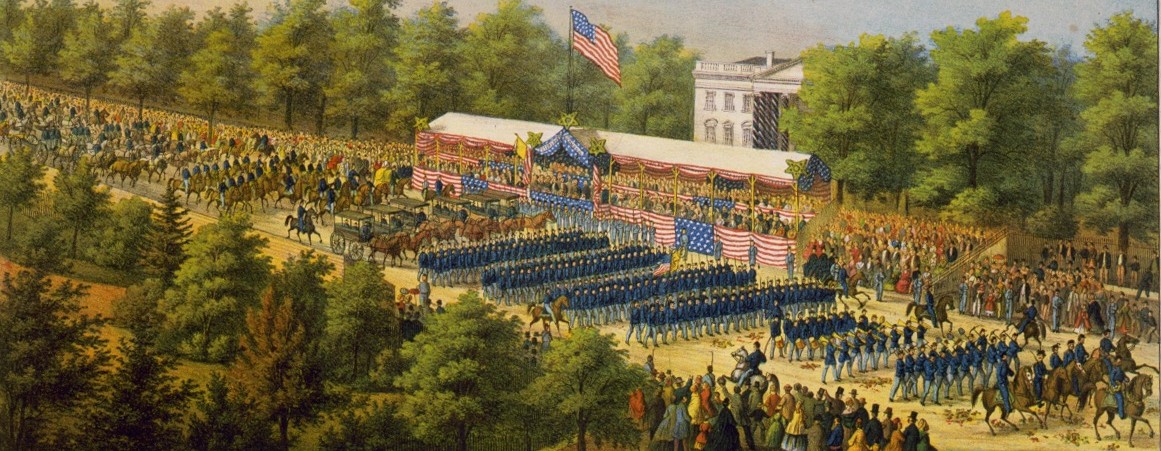

The sesquicentennial anniversary of the Grand Review in Washington, D.C. has given new life to an old myth about the lack of United States Colored Troop presence. This past weekend the African American Civil War Memorial & Museum in D.C. hosted a reenactment of the two-day march that included black reenactors.

For Sarah Anderson the reenactment was meant “to correct a wrong made in 1865, when black soldiers were left out of the Grand Review, the Union Army’s victory parade.” The oversight, as her article suggests, is part of a long history of racial injustice that leads directly to Ferguson and Baltimore.

Richard Kreitner, writing for The Nation also implies that black soldiers were intentionally left out of the festivities, that for many Americans signaled the end of the war and the triumph of the Union.

Excluded from the triumphant event, however, were the almost 200,000 black soldiers who had fought on the Union side, all of whom had been conveniently kept away from Washington.

The only problem with such an interpretation is that USCTs were not “conveniently” left out. Since the vast majority of black regiments were not raised until 1863 their terms of enlistment had not yet expired by May 1865. More importantly, as historian Greg Downs argues in his new book, they remained on the ground in much of the Confederate South enforcing the law and in support of emancipation.

These men were charged with maintaining the peace between ex-slaves and slaveowners and assisting with the former’s transition to freedom. Why wasn’t the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in Washington for the Grand Review? According to Downs, the 54th and other black units helped to maintain the federal government’s commitment to remaining on a ‘war footing’ for the immediate future. In short, as far as the federal government was concerned, the war had not ended in May 1865.

In August the 54th and 55th did triumphantly march through the streets of Boston to the steps of the capitol building to return their flags to the governor and muster on The Common one final time. Their service was honored, it just took a little longer to complete their duty.

We are naturally drawn to the past to explain contemporary problems. There is no doubt that the recent racial unrest in Baltimore and beyond has its roots in the past. At the same time we ought to be very careful when looking for these antecedent events. This picture of black soldiers enforcing emancipation in a hostile environment while their white comrades paraded through the streets of Washington certainly doesn’t compliment a memory of black men snubbed in the very moment of victory.

Sometimes the past is a foreign country.

News to all is that the 135th United States Colored Troop did in fact march in the Grand Review on May 24, 1865. It is documented fact. So the USCT’s were not left out of the parade as many will have you believe.

I watched C-SPAN’s broadcast of the Grand Review 150th tonight (6:30 EST). Dr. Frank Smith of the African-American Civil War Museum in DC was interviewed and he said USCT soldiers wanted to participate but were denied the opportunity. If I recall correctly, no mention was made about the soldiers being given another assignment anywhere.

From what I’ve read, I’m coming to the conclusion that the absence of XXV Corps USCT soldiers was not an overt snub but more of a sign of a time before people worked as hard as we do today to make sure that every group- or at least most of them- is represented in an event.

Anyway, I think it’s unfortunate that the Grand Review is perhaps best known for the men who were not there that it is for the men who were.

(1) I haven’t seen any white southern Union regiments mentioned as taking part. If there were none this might suggest President Johnson didn’t have much of a role in selecting the units to march..

(2) Apart from the dignitaries on the reviewing stand, was there much in the way of cheering crowds? I believe much of the non-official population of Washington was fairly disloyal, but I suppose they might have turned out for a show.

The Eighth Corps, which had been stationed in Maryland (and fought at Monocracy) also did not have a review –indeed they were used for crowd control at THE Grand Review. Nor were the white troops of Butler’s old Army of the James given a parade.

The decision to keep the USCT in use in the South was a political, economic and personal one: the USCTs were the last volunteers mustered out, long after most of the White troops had gone home. Economically this made sense, since many of these people had no where to go – sort of a “GI Bill” for them. Politically the Northern voters wanted the [white] Boys home (the same thing happened in 1945).

Of course the Western troops, except for those who had come with Sherman had no Grand Review, nor did Schofield’s men in the Carolinas. For that matter, Sheridan himself had been detached and sent to Texas to take command there against Maximillan and missed the Grand Review.

This discussion includes elements of the bizarre.

We read that “Excluded from the triumphant event, however, were the almost 200,000 black soldiers who had fought on the Union side, all of whom had been conveniently kept away from Washington.” Here’s an author who confuses the total number of enlistments with the total number available, as if not a single black Union soldier give his life for his country and his people’s freedom or were stationed anywhere else other than Washington, DC. One could be unkind and suggest that the author (perhaps unwittingly) overlooked that sacrifice and service of black US soldiers by suggesting that they were all healthy and ready to march.

Then we learn that the author finds that African Americans who serve as reenactors are his prime source of information for some of his claims:.”But I’m also aware, having spoken for hours with many USCT re-enactors on Sunday, that insofar as the American past is a landscape of race-based exclusion and subjugation, it does not at all feel to them like a foreign country.” Does this mean that because something’s true or felt today that it was the same 150 years ago? I guess that’s one way to learn about the past. Wait until he meets H. K. Edgerton.

Finally, we learn that the absence of evidence should not stand in the way of making claims about motive. As our author says, “This insistence on studious analysis of the most minute details of trees while the forest burns strikes me as an excellent argument against becoming a historian.” I accept that the author doesn’t want to be a historian or hold himself to the requirements of scholarly analysis. Let’s remember this line of argument when it comes to black Confederates. We lack evidence, there, too … or have some people forgotten the claim that the records of tens of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) of black Confederates were obliterated by someone, perhaps the same people who chose to exclude black soldiers from the Grand Review? Why, let’s follow the lead of the author of the article in The Nation and set aside sound scholarly practices altogether so that we can declare that our preferences, prejudices, and whims constitute real history. Then let’s remember that advocates of a significant black Confederate soldier contingent do the same thing.

Strange bedfellows indeed.

Well said, Brooks.

Parts of this discussion are a bit bizarre. We have an article in The Nation that deplores that all the African Americans who enlisted in the US Army … 200,000 men … were deliberately excluded from what in retrospect was a grand event. Of course, far less that 200,000 black soldiers were available: many had given their lives, while others were on assignment elsewhere. Should I conclude from this at best sloppy reporting that the author of the piece minimizes or ignores altogether their sacrifice and service by implying that every black who enlisted was nearby and healthy? No a minor point if we are going to engage in hair-splitting. Recall that Grant had made sure that black soldiers formed a part of the Lincoln funeral ceremonies, so it wasn’t as if the general in chief was adverse to their presence. And as for the lack of evidence somehow constituting evidence, let readers of this blog recall that advocates of a significant number of black Confederate soldiers often offer the same reasoning about the paucity of records documenting such service. Strange scholarly bedfellows, indeed. This seems to be a case where personal preferences and prejudices have overwhelmed the scholarly requirement of finding actual evidence to the point that the author of the article dismisses normal research practices as irrelevant to the matter at hand, and others let that go by untouched. Remember that the next time you read about tens of thousands of black Confederates.

According to Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain in “The Passing of the Armies” (published 50 years after the event), the only African Americans included were with Sherman’s Army of the West on the 3rd day. As has been mentioned, these consisted of pioneers, but also, “as a climax … whole families of freed slaves”.

On a side note, two things I noticed during the parade: the General Grant equestrian statue in front of the Capitol was covered up with a cloth and in the process of restoration. Too bad the general couldn’t even see his soldiers march. But a big picture of Lincoln was hanging in front of the Newseum building on Pennsylvania Avenue. Looks like Lincoln finally got to see the Grand Review, 150 years later.

Good to hear that the Grant monument is finally getting some attention. It is long overdue.

I think it just depends on whether you like your racism/insensitivity hard or soft.

Hard would be, “no blacks allowed in the parade.”

Soft is, “you know, they would have been here, but we decided they were just the one corps out of the half dozen or so around Richmond that we wanted to ship all the way to Texas and, even though they were still waiting for the boats on that particular day, we didn’t want to trouble them by taking them out of their way.”

It makes me think of the way a lot of folks react when they do or say something insensitive these days. They can’t be racist, because they didn’t mean to be.

Of course, you can argue that 150 years ago they had a lot more of an excuse. But this last Sunday, I was glad I got to march with Bryan and the others. It did feel like a long time coming. And it did seem about the best possible way to wrap up the events of the 150th cycle.

I think it’s important to remember the context in which this claim is being made. In both cases (one more so than the other) the authors reference the supposed snub as part of a long narrative of racial discrimination that helps to explain current problems. Now I am the first person to admit that the history of racial discrimination is incredibly rich going back to the Civil War era and beyond, but this tendency to accept this claim without question masks the broader history.

At just that moment black soldiers were actively engaged in enforcing emancipation in the heart of the now defunct Confederacy. In fact, they were actively liberating slaves in areas that had not yet been informed of the end of the war or whose masters resisted emancipation. I have to wonder how many of these black soldiers would have preferred to parade through the streets of D.C. rather than continue with their work.

“At just that moment black soldiers were actively engaged in enforcing emancipation in the heart of the now defunct Confederacy.” That may be true, but it’s irrelevant to the point that their number did not include the 25th Corps waiting for its boats near City Point, who might nearly as easily have got on them at Washington.

I was making a general point about black soldiers during this period. What I am trying to show is that the popularity of this narrative of snubbed black soldiers overshadows the important work that they carried out during this period.

And I believe that the situation of the 25th A.C. shows that black troops actually were snubbed — not perhaps as deliberately and crudely as some would have it, but with the same effect. “The old myth” you mention at the beginning of your post has more than a grain of truth in it.

I wonder whether you believe that if Lincoln were still alive there would have been no black troops present at the Grand Review.

I’m fully aware, not least from reading Gallagher, that there is no smoking-gun evidence of intentional exclusion. But I’m also aware, having spoken for hours with many USCT re-enactors on Sunday, that insofar as the American past is a landscape of race-based exclusion and subjugation, it does not at all feel to them like a foreign country. This insistence on studious analysis of the most minute details of trees while the forest burns strikes me as an excellent argument against becoming a historian.

I wonder whether you believe that if Lincoln were still alive there would have been no black troops present at the Grand Review.

To what extent did the executive branch have anything to do with the Grand Review? I don’t know the answer to that question.

But I’m also aware, having spoken for hours with many USCT re-enactors on Sunday, that insofar as the American past is a landscape of race-based exclusion and subjugation, it does not at all feel to them like a foreign country.

I wasn’t suggesting otherwise; in fact, much of my research reinforces just that point.

This insistence on studious analysis of the most minute details of trees while the forest burns strikes me as an excellent argument against becoming a historian.

It’s certainly not for everyone. Apart from evidence we are free to draw whatever conclusions we want and/or repeat the same old stories. Thanks for the comment.

Black troops did get a parade in Philadelphia with plenty of admirers and reviewers. Was it to the same stature as the Grand Review, no, but it was still a parade. There’s also something to be said that, if Brian Jordan’s book is anything to go on, many Federal veterans saw the parade as just one more obstacle before home. Some didn’t care about the parade at all.

Good point re: Jordan’s book.

I participated in the Grand Review 150th on Sunday and it was a great event (BTW, in spite of what Sarah Anderson says in her article, no reenactors had great coats on; it was way too warm for it).

Anyway, thanks for posting this because I don’t think it’s best to look at the exclusion of Black soldiers from the Grand Review in a vacuum. Remember that just a couple of years before the Grand Review, many people wondered if Blacks would make good soldiers at all. But they proved themselves in combat. They were the first troops to enter both Charleston and Richmond when those cities surrendered. And as you pointed out, they were assigned to police the peace in the South and the Southwest.

It would be great if we could find any firsthand accounts of how Black Union soldiers felt about not being a part of the event. Certainly, the North had a long way to go in racial inclusion in May 1865. But there is a big difference between “not present” and “not allowed.”

Thanks for the comment, Bryan.

It would be great if we could find any firsthand accounts of how Black Union soldiers felt about not being a part of the event. Certainly, the North had a long way to go in racial inclusion in May 1865.

I agree. I’ve spent some time with the correspondence of members of the 54th Massachusetts with black newspaper up North and they don’t make much of any reference to it. The context that you sketch is absolutely essential to understanding the situation of black troops at the end of the war and through the very early stages of Reconstruction. That they were kept in the South after the war could is quite telling.

Thanks for your response, Kevin. For what it’s worth, there seems to be an “Appomattox Syndrome” quality to the memory of Black troops left out of the Grand Review (“Appomattox Syndrome” is Gary Gallagher’s term for interpreting the war based on knowing it ends in Union victory). I get the idea some people are thinking, “Of course Black troops were left out of the event” as we know it would be 100 years before African-Americans would legally achieve civil rights.

As a side note to the logistics issue, General Weitzel wrote on May 27 that the first elements of the 25th A.C. had just embarked; General Jackson reported that the first elements of the Second Division did not get to sea until May 29. While the Grand Review was underway, the black soldiers of the Army of the James were still cooling their heels in the vicinity of City Point.

Yup.

To say the 25th Corps should have been in Washington instead of preparing for movement is akin to saying the military commanders should have suspended operations for the sake of some “show.” And if you submit that counter-factual premise, there are several points which should be addressed:

1. What was the official purpose of the Grand Review? (Orders were posted, from the War Department, explaining the purpose of the “show.” I suggest you refer to that to determine if it was within the scope of those orders to have troops other than the Armies of the Potomac, Tennessee, and Georgia in the review.)

2. Was there sufficient shipping to move an entire Corps from City Point to Washington? Before answering, note that the three armies that participated in the review did not move by boat. They marched. And their march had to be sequenced very carefully to avoid congestion. It is far more likely that HAD the 25th Corps been called upon to participate, they would have moved by foot (the 25th was, largely, waiting on boats for Texas, due to an acute shortage of shipping on the eastern seaboard which hindered Federal operations in late 1864 well into 1866). AND that would have added one more command moving to the appointed place/time. So one must pull out the maps and demonstrate how that movement would have taken place, among the other movements occurring at the same time. … Hint.. I’ve already done that for you to an extent on my blog, examining the movements of Sherman’s command in this same period. There is a reason the 14th, 15th, 17th, and 20th corps all took separate lines of march into Alexandria.

3. What was the 25th Corps doing on May 27? We must address what “cooling their heels” looked like on the ground. I would submit, based on the dispatches and reports posted at that time, the formation was not simply sitting about the docks “cooling their heels.” Rather they were engaged in the multitude of activities required of a unit that is transferring formerly assigned duties to replacements and preparing for a follow on mission. That, of course, was a far cry from “cooling their heels.” Perhaps the term “refitting” is best applied. And that term implies something more than inactivity on the part of the troops. And if we prescribe a break in that activity, we must factor that – by sliding a time line to the right – for those troops in their follow on mission. And would that mission wait the couple of weeks of “slide to the right” which would occur? A question, by the way, which should be answered in the context of what the commanders knew at that moment in time, and not what we know of the future which unfolded later – regarding Mexico and Napoleon III.

Lastly, I am compelled to bring up something overlooked in much of this discussion – there was indeed a formation of blacks that marched in the Grand Review. The men who had accompanied Sherman’s march as part of the organized pioneer corps, along with those who had served in other support capacities, marched behind the Army of Georgia. Those men were recognized as a vital component of Sherman’s force. Yet, 150 years later, they are largely forgotten.

I’m compelled to draw a comparison between those men who supported Sherman’s march and the alleged “Black Confederate soldiers.” If on one hand we are told to accept the service of a teamster or cook as being “a soldier”… then must we also say the members of the Pioneer Corps that cleared roads, laid corduroy, and completed other tasks that directly opened the road to victory in the Carolinas deserve similar categorization?

Well said, Craig

Troop movement in combat conditions…and make no bones about it…in Southside Virginia the US Army was still on a war footing…is very difficult.

And after the Spring campaigns there is no doubt much refitting had to occur. Especially if the XXVth Corps was shipping to an austere theater like TExas, well away form the supply depots of the East.

Well, no one’s suggesting that military operations ought to have been “suspended,” only that some operations — like the parade itself and the redeployment to Texas — could have been managed differently. Apart from that, I think your arguments illustrate the lengths we can go to when we wish to explain away the unpleasant consequences of decisions with racial repercussions.

1. To say that blacks could not march in the Grand Review because the orders didn’t include the Army of the James is just to say that the “snub” was due to the orders, not whoever issued them, which really is no argument at all. As I said initially, the 25th Corps was functionally part of “Grant’s” army all through the campaign and belonged in that parade as much as anyone.

2 . The 25th A.C. could have moved by foot or boat. To say the roads were crowded while the AOT and AOP were racing to Washington is not to say that they remained crowded for days or weeks after. Some 150,000 men composed those two armies, but somehow no room remained for another 15,000 in their immediate wake? Did they carry the roads with them as they marched along? As for shipping, shipping was also at a premium in mid-1864 at the height of the campaign season, but Grant nonetheless managed to send some 4,000 dismounted cavalry and the entire 6th Corps back to Washington for its defense against Early. A lot of boat traffic went back and forth from Washington to City Point, and they were not the same boats that were needed for a lengthy excursion beyond the Chesapeake.

3. I’m sure the men of the 25th A.C. found ways to fill their time before the trip to Texas, but I doubt that they couldn’t have done the same in Washington. After all, Sherman and Grant’s other men had to do some “refitting” too.

Finally, everyone knows that Sherman had his “pioneers” and contrabands in the parade. The press of the time was much amused by the sight. But that made an entirely different kind of “show” from the one that would have been presented by an army corps of black men. Surely that can’t be difficult to understand.

And no, there’s no comparison here to “black Confederates.” The 25th A.C. existed, it fought alongside Grant’s other corps in the final, decisive campaigns of the war, but when the fighting ended and the victory celebration was held, they weren’t there. The only real discussion is whether this resulted from a deliberate act of racism, or a passively racist oversight.

“To say that blacks could not march in the Grand Review because the orders didn’t include the Army of the James is just to say that the “snub” was due to the orders, not whoever issued them, which really is no argument at all.”

Let us not continue with speculation and confabulation here. I’ve offered some threads to follow on your exploration if this issue. There was no “snub.” There were orders for specific units to move to Alexandria for specific military purposes. Those purposes deserve far deeper treatment than can be summarized here. Suffice to say the “review” was not some conspiracy, as you allude to here, in order to subvert the contribution of the USCT. In all reality, the review was an opportunity event that included the units which happened to be around DC at the time. No units received orders to march to DC “in order to participate in a grand review.” Rather those units received orders to march to DC as part of their muster out. These were “Meade’s” and “Sherman’s” commands, minus several large formations (both white volunteer and USCT alike) who were not due to muster out and had other responsibilities. (For example, I’m sure the 23rd Corps would have LOVED to have marched north with their fellow westerners… but they had other matters to attend to.)

Simple fact of the matter – the USCT units in the 25th corps were not due to be mustered out, were being sent on additional missions, and did not have time to march to DC and then parade. It was not the result of some racist conspiracy, as you have alluded to.

“The 25th A.C. could have moved by foot or boat.”

Again, you are offering a counter-factual here. It is your responsibility to offer support for that. What boats would be diverted from appointed missions? Or, what route would the 25th take to get to Washington? For the latter, I suggest you consult the ORs and look through the time lines and lines of march. I offer that you will quickly learn that the roads towards Northern Virginia were at that time filled with Federals of all sorts. Recall, the AOP was followed by the western armies – a force nearly twice that which had marched south in the Overland Campaign a year earlier, including seven corps of infantry. To add another formation there, by way of conjecture, you have to demonstrate how that could have occurred. If you cannot respond with routes and times, then we must agree that matter was a logistical shortfall which speaks against your counter-factual. That’s how we resolve such points.

“I’m sure the men of the 25th A.C. found ways to fill their time before the trip to Texas, but I doubt that they couldn’t have done the same in Washington. ”

Well, let’s go back to the source materials here. The 25th was told to prepare for movement from the James River ports because that was where the logistic system could best support said movement. Their equipment was in the Petersburg-Richmond area. The transportation taking them to Texas could best reach them on the James River. These points are laid out elaborately in detail by BG Meigs at that time. If you are saying a different arrangement could have been made, then you must offer some counter to Meigs’ arrangements. Otherwise, again, there is a shortfall to your counter-factual.

There also seems to be a misconception in regard to the Grand Review itself, which comes through in your responses. WE might see it as a “victory parade” of the sort which followed WW II or maybe the Gulf War. And there is no denying that the event served as one of the “mission accomplished” ceremonies for the Civil War. Reality was, like the infamous “mission accomplished” event of recent memory, the Grand Review was not planned as some banner-worthy event (though the flag-raising at Fort Sumter the previous month was certainly that sort of event!). Rather it was planned as a formal, military “farewell” to veteran soldiers of specific units which had served in key campaigns, under prominent leaders, during the war. The event was afforded by the circumstance of three major field armies returning to their muster-out point at the same time.

Thanks, Chris. This is incredibly helpful.

I don’t see where you’ve addressed the substantive question of how another 15,000 men could not have made a march on roads that had already accommodated 150,000, or how they could not have moved by water as swiftly as the reinforcements sent by Grant over a few days in July 1864. Unfortunately, most of your verbiage seems devoted to umbrage rather than fact.

It’s called “traffic.” Ever tried to drive north on I-95 on a Sunday afternoon?

“The only real discussion is whether this resulted from a deliberate act of racism, or a passively racist oversight.”

The absurdity of this line bends all rational thought and reason. So… we are to accept that BG Montgomery Meigs was “racist” because he decided the best place to send off the 25th Corps was the James River instead of Alexandria? Please, enlighten us on this undeveloped aspect of Civil War logistics…..

Speaking of absurdity, with the exception of the provisional division of the Defenses of Washington on a few days in July 1864, Meigs did not direct the placement of any troops.

Michael

As for placement of troops….

The defense of Washington was a battlefield operation wherer Miegs had no command or control.

The movement of units to Alexandria was an administrative move. The quartermaster general’s office was responsible for all placement of tropps in an administrative move.

That would be Miegs.

Even Grant’s Headquarters troops would have to conform to Miegs orders.

Its called march orders and western armies have been doing in for centuries.

Don’t conflate battlefield operations with administrative ones.

The only real discussion is whether this resulted from a deliberate act of racism, or a passively racist oversight.

I am not sure this tells us much of anything about the decisions that were made at this time.

No, it doesn’t tell you much about decisions at the time because it responds to excuses being made today. Racism at the time was an unremarkable fact and I don’t find it especially disturbing from the perspective of 150 years later. But I do find it a mite dismaying to see the lengths folks will go to in order to deny it today.

Speaking of decisions at the time, I just took another look at Dobak’s “Freedom by the Sword” to see what light his work might have to shed on this. On pp. 422-423, after a discussion of disciplinary issues in the 25th A.C., he gets to the decision to send the corps to Texas. MG Hartsuff in Petersburg’s statement about the issues seems to sum up the concerns fairly: “…exciting the colored people to acts of outrage against the persons and property of white citizens. Colored soldiers [have] straggled about advising negroes not to work on the farms…” &c. Although senior officers of the 25th A.C. objected to generalizing these concerns, Halleck seems to have decided, and Grant concurred, that the best way to deal with the situation was to get the corps out of Virginia. This according to Dobak.

So now I’d have to rephrase my earlier question about hard-boiled and soft-boiled racism. It’s not really “no blacks in the parade” vs. “don’t want to disturb them while they’re waiting for their boats to Texas,” it’s “no blacks in the parade” vs. “we want these fellows out of here as quickly as possible before they abuse all the white women and spread their uppityness to the other black people.”

With that, we’re left trying to balance the racism of outright exclusion with the racism of stereotyping and profiling an entire corps of the United States Army, but we’re still stuck with the “snub” and the fact of racism.

With that, we’re left trying to balance the racism of outright exclusion with the racism of stereotyping and profiling an entire corps of the United States Army, but we’re still stuck with the “snub” and the fact of racism.

It would be more accurate to say that you are left with the snub of black troops at the Grand Review. I have yet to see any evidence that these units were intentionally left out.

The snippet about the Grand Review in Gary Gallagher’s Union War is online thanks to Google Books. I included the link below.

https://books.google.com/books?id=j4SKGERSbsAC&lpg=PA21&ots=3lzvAmaPmf&dq=The%20Liberator%20Black%20Pioneer%20soldiers%20Grand%20Review&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q=The%20Liberator%20Black%20Pioneer%20soldiers%20Grand%20Review&f=false

The 29th CT CVI came back to the state in November, 1865 after serving in Texas. They were met by Governor Buckingham who addressed these veterans on November 25th. His words are worth remembering: “And although Connecticut now denies you privileges which it grants to others, for no other apparent reason than because God has made you to differ in complexion, yet justice will not always stand afar off. Remember that merit consists not in color or in birth, but in habits of industry, in intellectual ability and moral character. Cultivate these characteristics of true worth. Show by your acquirements and your devotion to duty in civil life, that you are as true to virtue and the interests of government and country, as you have been while in the Army, and soon this voice of a majority of liberty-loving freemen will be heard demanding for you every right and every privilege for which your intelligence and moral character shall entitle you. Again, I ask you to accept my thanks for your patriotic services, and my best wishes for your prosperity and happiness.”

Hi Tim,

Thanks for sending this along. It points to the fact that there were many ‘grand reviews’ in the months following Appomattox.

They got Grand Reviews without Grand Reviewers.

I am not sure I understand the distinction.

By and large these went unnoticed beyond the communities in which they occurred. No Grant, Sherman, Johnson or Stanton. No large crowds.

I would have to go back and check newspaper reports on the Boston crowds.

No large crowds.

Do you know this for a fact?

What is relevant is that they took place at all in contrast with your suggestion that they were intentionally left out.

Perhaps I am missing something here. In most cases, blacks were not in state regiments. While some units were given warm welcomes, like the 54th Mass., did most really ever “go home” in the sense of parading in an event even remotely as grand as the Grand Review.

I am not suggesting that they were widespread. Black regiments also paraded through Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but I offhand I can’t tell you where else. You make a good point that those men not in state units likely didn’t experience a formal review. I am also not suggesting that they were on the scale of the Grand Review.

What is driving this post is the claim that black units were intentionally snubbed for the Grand Review. As things stand, I see no reason to believe such a claim.

I, too, don’t see that they were intentionally snubbed. However, what if they were? Does having re-enactors participate in a re-enactment of a Grand Review from which they were excluded really do anything or have an effect on the conditions leading to the Fergusons and Baltimores? Not at all. It’s more of a feel good kind of thing but that’s about it.

It’s more of a feel good kind of thing but that’s about it.

I have no problem with that. I suspect it is incredibly meaningful for those involved.

Thanks for this Tim, very interesting and uplifting. Alas, when Governor Buckinghma said

… soon this voice of a majority of liberty-loving freemen will be heard demanding for you every right and every privilege for which your intelligence and moral character shall entitle you.”

he was too optimistic, by at least 100 years.

And not all white units were present either.

Don’t know of representatives of Army of the Gulf, Army of the West and myriad other Union formations. They got their parades, just not in Washington

Heck the AOP’s VIth Corps didn’t particiapte. They were supervising the parole of the remainder of the ANV troops as well as dealing with the removal of Confederate public property from the Appomattox area. It took a long time for the Southside Railway to move the weapons, etc, to City Point.

The issue is not why not all white troops were there, it is why not a single black regiment participated. It would have been simpler to bring a USCT from Richmond than it was to bring some of the Western units to Washington.

Why did the parade even include Western troops? They had nothing to do with the defense of Washinton. It was obviously to show the national scope of the Union struggle and to honor the men who had won the war. Exclusion had obvious implications.

The issue is not why not all white troops were there, it is why not a single black regiment participated.

OK, but there doesn’t appear to have been an order to exclude black soldiers. While we find it unusual, it doesn’t appear that the nation did in May 1865 and as I stated in the post, cities like Boston had no problem welcoming these men home later that summer.

In looking at racial discrimination cases, the existence of an “order”, while helpful, is typically not necessary. In this situation, you had an institution, the Union Army, that paid blacks less, segregated them from whites, and largely barred them from officers’ ranks. At this point the army had a sizable number of black regiments, African Americans having been excluded from “white” regiments, but none were put in the line of march.

Not a tough case to make at all.

As you know I am well aware of the discrimination faced by black men as soldiers in the United States army.

“In this situation, you had an institution, the Union Army, that paid blacks less, segregated them from whites, and largely barred them from officers’ ranks. At this point the army had a sizable number of black regiments, African Americans having been excluded from “white” regiments …”

These things were all done through an “order.” (Not sure why you put it in quotes.)

If any entity engaged in these systematic forms of announced discrimination and then did not have any units from the discriminated against class participate in a high profile activity that involved hundreds of white units, some travelling over considerable distance to participate, the evidence of de jure discrimination would go to the issue of de facto discrimination.

Entities that have written policies of racial discrimination are more, not less, likely to engage in informal or unwritten forms of discrimination.

Pat,

The Grand Review was not about the troops who defended Washington. It was about the 2 primary field armies which defeated the Rebellion marching in the Nation’s Capital marching in celebration and being acknowledged by the Nation’s political leaders.

It was a political statement (see the parades in NYC & Washington after the Gulf War).

Was there a conscious decision to exclude USCT? I don’t know if it was racial or if the USCT were the Army in being which was not going to be discharged right away and so were kept on the frontier or keeping the peace throughout the vanquished South.

Was racism institutionalized within the US Army….hell yes…just like society.

But let’s also acknowledge that the Soldiers of the armies of the Potomac, Tennessee & Cumberland had shouldered the greatest burden of combat. And their blood and the blood of their past comrades earned them the right to pass in review in Wasington. As a Soldier that is considered a high honor (speaking as one who has done that).

I totally agree the USCT and Black USV Soldiers fought well and deserved to be included.

But I do not think it right to imply that the AOP, AOT and AOC Soldiers didn’t deserve the recognition.

Remember these were the men who LIVED the words:

“As He died to make men holy

Let us die to make men free…”

Buck, when you write: “But I do not think it right to imply that the AOP, AOT and AOC Soldiers didn’t deserve the recognition.” I have to wonder if you are still addressing me, since I never implied that.

I guess I was mistaken or misingterpreted you point.

My apologies.

Also in Gary Gallagher’s “Union War” Dr. Gallagher makes a pretty convincing argument that USCTs were not deliberately discriminated from the Grand Review.

It seems to me that the question, “Who was excluded from the parade?” is a *history* question. Wouldn’t the *memory* question be, “Was this exclusion celebrated in Civil-War-memory or passed over in silence?”

Beyond a few newspaper references I don’t believe it was noticed at all. Like I stated in the post cities like Boston held elaborate ceremonies for the return of their black soldiers at the end of the summer.

The Army of the James was functionally part of “Grant’s” army, not geographically separated like the Army of the Cumberland and other nonparticipants in the Grand Review. The 25th Corps accounted for 10-12% of the troops on the Richmond-Petersburg front, which is how they ended up being among the first soldiers into Richmond and having a couple of brigades present at Appomattox.

The 24th Corps went on immediate occupation duty; the 25th were going to Texas, and it’s reasonable to ask whether it would have been logistically that much tougher to send them to Washington for embarkation so some could participate in the parade.

The expiration of enlistment argument is a little dicey — you’d have to know when every unit enlisted or re-enlisted. Many USCT enlisted for only a year. Many white “veteran volunteers” had re-upped for three years at the end of ’63. The demobilization of the two main armies was driven more by the War Department’s rush to reduce expenses than an analysis of actual expiration dates.

I haven’t found any evidence that someone flat out said “No USCT in the parade.” But certainly race was a factor in forming the 25th Corps, in denying commissions to black officers in all but a few cases, in considering black troops particularly suited for duty on the Rio Grande, and in not deciding that there was a particular value in having them represented in the Grand Review.

Racism is not binary, with one either being or not being racist. It can be direct or indirect, hard or soft, and include acts of omission as well as commission. The exclusion of the 25th Corps from the Grand Review wasn’t perhaps a “whites only” act of racism, but it doesn’t really soften the blow to say that the thought of including them simply didn’t occur to the organizers.

Thanks for the comment, Michael.

The question of enlistments is more complex than what I suggested in the post and as you know plenty of white regiments remained in the South following Appomattox. You are correct in pointing out the financial considerations driving demobilization, but Downs notes that Congress and President Johnson remained committed to maintaining a large military presence during the initial phase of Reconstruction to enforce the law and support the freedmen.

Racism is not binary, with one either being or not being racist. It can be direct or indirect, hard or soft, and include acts of omission as well as commission. The exclusion of the 25th Corps from the Grand Review wasn’t perhaps a “whites only” act of racism, but it doesn’t really soften the blow to say that the thought of including them simply didn’t occur to the organizers.

Excellent point, but let me be clear that I am responding to the rather simplistic explanation that these men were intentionally left out of the parade without any awareness of the larger picture that I briefly sketched in the post.

I understand, appreciate, and — in the absence of some evidence to the contrary — agree with the argument against the simplistic conclusion reached elsewhere.

I just don’t buy it. If Andrew Johnson had wanted a single black regiment to march, it would have marched.

Have you picked up Downs’s book? You might be surprised by how he situates Johnson in the earliest phase of Reconstruction

I read the complete book.

Part of this is my Appalachian roots giving me an auto-pilot to defend Johnson; he’s Appalachian, not Southern.

Not all white armies marched in the Grand Review. If I’m not mistaken, troops that marched in the Grand Review were a part of the Army of Potomac and Armies of the Tennessee and Georgia. I did not believe that any black regiments were assigned to these armies. Black troops in the Army of the James were about to be shipped out to Texas; they were still on active duty as Kevin said.

Black troops did participate in Lincoln’s inaugural parade in march. They participated in Lincoln’s funeral in April. And, in a very small quantity, some black soldiers marched in the Grand Review. There were a very small amount of black “pioneers” who were in Sherman’s army.

In addition to Downs, the first chapter in Gary Gallagher’s “The Union War” does a fine job of addressing USCT deployments in the Confederate South during the Grand Review.

Yes. Well worth reading.

Read that one too. Sorry, but it is obvious that blacks could only appear as laborers.

Not sure what you are getting at, Pat. I assume you are suggesting that these men were intentionally snubbed.

They were allowed to appear as “pioneers”, essentially laborers, or in roles that reminded me of minstrel shows. They were not permitted to appear as men of war marching.

I find this first series of exchanges as interesting as the post. I think these are classic examples of how different people interpret the same thing, and dare I say with some emotion from Pat and Rob.

Rob is right about Johnson being Appalachian than Southern. And are we surprised that he, even without issuing an order, didn’t include black troops? Kevin is also right that most of what happened, and didn’t happen, was because of unit muster out dates. I guess Johnson could have pulled a few USCT units into the parade, but then wouldn’t that have been just token choices, since they weren’t yet mustered out? Heck, the 183rd Ohio Infantry was in NC and got left behind (along with several other regiments) when the rest of Sherman’s boys went to DC because its term was not up till July. It seems that Pat is saying an exception should have been made for the black troops, i.e. treat them differently.

Perhaps they should have been, considering the war’s causes and implications and results, but they weren’t. And I’m sorry, anyone who links the Grand Review with the nonsense in Baltimore is missing altogether more important. I’ve talked with plenty of black friends over the past few weeks who are absolutely sickened by what they saw play out on the streets there.

Pat,

“Pioneers” are a brigade that originally formed in the Army of the Cumberland. They were a bi-racial brigade by the war’s end, though the unit deserves more research. They were not, in any way, simply laborers.