At the very beginning of his new collection of essays Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a few thoughts about the historical significance of the Confederate slave enlistment debate. According to Coates the debate itself reflects a deeply ingrained and long-standing “fear” that assumptions of black inferiority are unfounded.

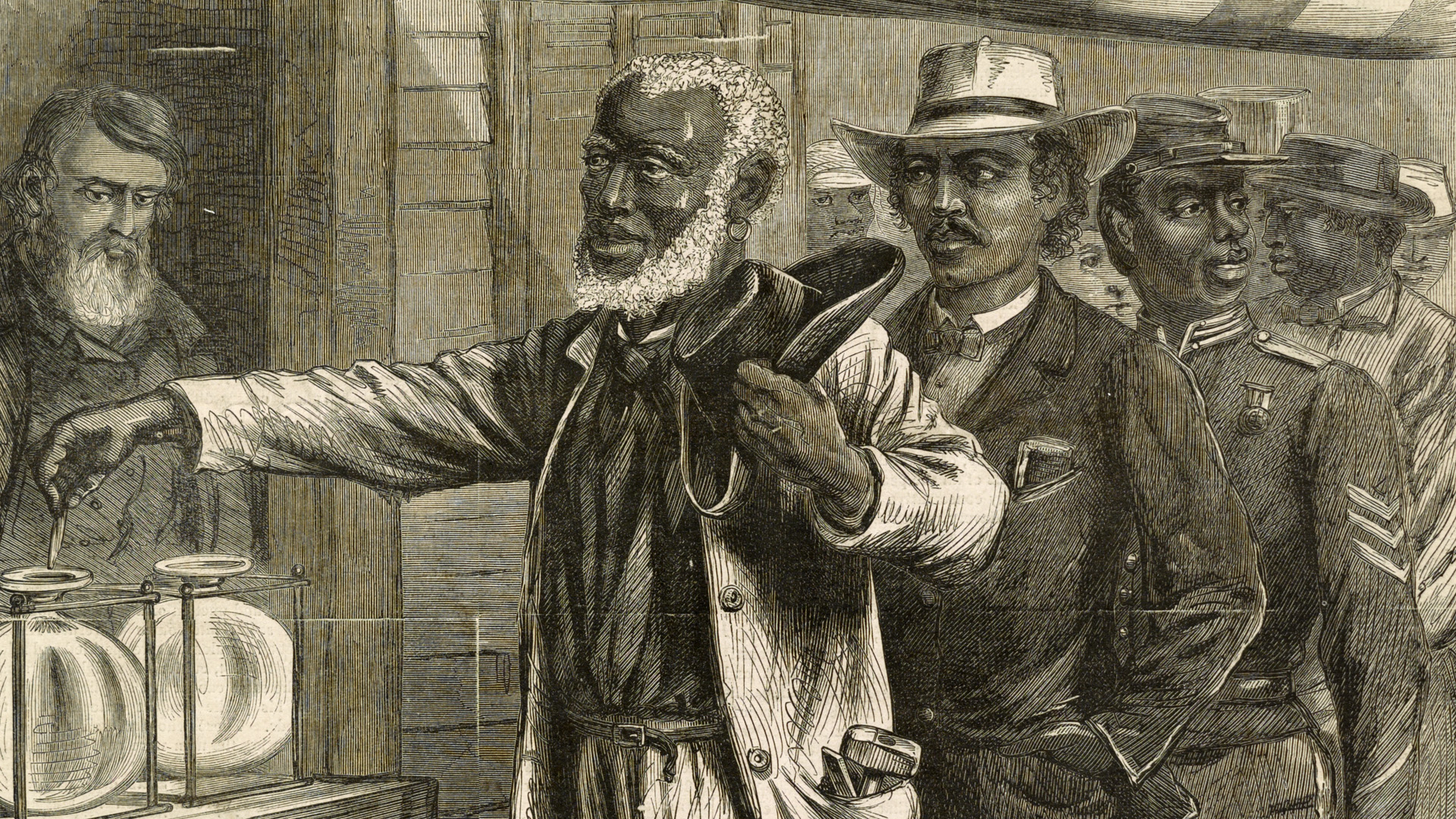

The fear had precedent. Toward the end of the Civil War, having witnessed the effectiveness of the Union’s “colored troops,” a flailing Confederacy began considering an attempt to recruit blacks into its army. But in the nineteenth century, the idea of the soldier was heavily entwined with the notion of masculinity and citizenship. How could an army constituted to defend slavery, with all of its assumptions about black inferiority, turn around and declare that blacks were worthy of being invited into Confederate ranks? As it happened, they could not. “The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of our revolution,” observed Georgia politician Howell Cobb. “And if slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” There could be no win for white supremacy here. If blacks proved to be the cowards that “the whole theory of slavery” painted them as, the battle would literally be lost. But much worse, should they fight effectively–and prove themselves capable of “good Negro government”–then the larger would could never be won. (pp. xiv-xv)

Coates beautifully nails down the racial implications of the debate for a nation committed to creating a slaveholding republic around white supremacy, but I wish he had taken the argument further. It is true that the United States embraced black men to help to save the Union by 1863, but the same questions that paralyzed the Confederacy until the final weeks of the war were at the center of the debate in the United States.

Could black men fight effectively in the ranks and if they could what did that mean for assumptions of black masculinity and black inferiority held by the vast majority of white Americans? The United States took the plunge into arming blacks and as a result was forced to confront the very questions and fears that defeat saved Confederates from having to confront.

One of the things that I have come away with having read extensively among the primary sources related to the Confederate slave enlistment debate is that it must not be brushed aside as the final chapter in a failed slaveholders rebellion, but as part of a broader American conversation about race that we are still writing.

When I read or hear the thoughts of neo-Confederates/Lost Causers/Confederate apologists/those who wish the South had won/etc. who believe in thousands of Black Confederate soldiers, I feel like they’re saying, “Wow!

You know, Black people aren’t so bad. I wouldn’t mind having one of them on my team (that is, one who’s non-threatening to my ideas and worldview).” In a strange way, it really is some people’s response to the success of the integration that the White Confederates they also glorify fought so hard to make sure never happened.

But since we’re talking about the response of White Confederate soldiers to the idea of having Blacks serve with them, I’d like to ask this: what about how White Union soldiers felt about the reality of the United States Colored Troops? I have read the words of many, who unfortunately were just as racist as the Confederates. And yes, some Yankees did cheer on the Black troops. But, especially in the 19th Century, ideas of manhood (the brain; the heart; the nerve, à la the Wizard of Oz, if you will) were so wrapped up in military service. So what did the inclusion of Black soldiers communicate to Union men? That they were not man enough to win the war and defeat the rebels without the help of the USCT? I suppose you could even apply this to the enlistment of Irish and German immigrants, men who were often seen as “less than” in what it meant to be White in the 1860s as well. I believe I can understand why Southern rebellion flounders when they looked around in early 1865 and pretty much all that was left to them as a resource for military manpower were Black men. But in a lot of ways, it’s truly amazing that it was embraced in the North at all.

Did any Confederates suggest that Black Confederate might go over to the Union at the first opportunity? And were any of the proponents offering to lead such units from the front?

I haven’t come across much that suggests that this was a widely held view. Certainly Northern cartoons anticipated this. Yes, there were a number of people who volunteered to lead black Confederate units.

Just how did the Confederate proponents of Black enlistment think they were going to motivate Black Confederate soldiers to fight against their liberators?

They would be given their freedom after the war.

That was part of the legislation that was passed, but it said nothing about family or the broader population. This is not a plan for emancipation and it is not at all clear how this policy would have played out given the resistance to it, including resolutions against it from states like North Carolina.

Interesting. I just found your blog, and the subject of Confederate slave enlistment is one I have always wanted to explore further. I’ll definitely have to pick up Mr. Coates’ book. Is there a book that references and examines North Carolina’s position against slave enlistment and/or freedom for military service?

The best book to read on the slave enlistment debate is Bruce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation, which you can pick up in paperback.

I’ve been involved in the debate (I’m not sure what to call it) on Black Confederates for many years, especially on the CompuServe Civil War Forum. At some point, I find, when one points out the massive problems with the idea, that one gets attacked for minimizing the abilities, will, etc. of Blacks in the rebel states. I generally respond that, while I certainly don’t, that’s not the real issue. The issue is the attitude of the white power structure in the Confederacy. It wasn’t just that they didn’t care about what the Blacks within the area they controlled wanted. They, to paraphrase the Dred Scott decision, actively believed that Blacks did not have attitudes worth considering. To me, among the most critical points to look at are (1) the rebel reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation and the US Government’s decision to allow Blacks to enlist in the US military; (2) the reaction both among the generals of the Army of Tennessee and Jefferson Davis to the Cleburne proposal; and (3) the reaction to Davis’s proposal to allow Black in the Confederate armies as defeat loomed at the end of the war. There is also the reaction of Confederate troops and commanders when facing Union regiments consisting of soldiers who were Black. All of them show an overwhelming rage at the Union for having Blacks in the their armies, especially in combat, and Cobb’s recognition also expressed by the reaction of some of the limited number of people aware of Cleburne’s proposal and the suppression of any further mention of that proposal. They would rather go down to defeat than make any concessions on the rightness of slavery.

I do believe this is the biggest reason the Louisiana Native Guard, made up of creoles and blacks was refused by the CS National government. i.e. Men of color as soldiers undermines white superiority.

That is why I so often reference Robert E. Lee’s letter to Andrew Hunter written on January 11, 1865 when discussing the Confederacy’s stance on slavery and racial superiority. Not only was Lee a Southern gentleman a member of the Southern aristocratic elite and planter class, but he also is a nexus and focal point on the issue since he was the commander in chief of Confederate forces at the end of the war.

While in his letter to Hunter Lee does admit that they need to enlist slaves to save the Confederacy the first paragraph of the letter summarized superbly the predicament the entire Confederacy was in at the end of the war as well as shows the hardline stance the Confederacy had taken to that point in the war on Confederate emancipation and the enlistment of slaves in the Confederate armies. Also for more in depth research on this topic, my former professor Bruce Levine’s book “Confederate Emancipation” is excellent as well.

Lee’s call to enlist slaves as soldiers also fits into his thoroughgoing nationalism. By the end of the war he believed that the Confederate government had the right to impress anything it needed to win the war. This is a point emphasized by Gary Gallagher that re-casts Lee as a modern general.

“As it happened, they could not. ”

Isn’t this exactly wrong? The “Confederate States Colored Troops” were approved by the Confederate Congress a few weeks before the war ended.

My point is that they were approved only after they could reasonably have been expected to make a difference.

They were also approved after the Confederacy had tried to get men every other way- enlisting men for the duration; the draft; offering Union POWs release from prison camp if they fought for them; attempts to raid prisons holding captured Confederates to get those men released; lowering and raising the ages of enlistment; and recruiting men from overseas.

No, in the sense that very few slave soldiers were ever recruited, none actually fought and they were treated like prison inmates rather than soldiers. Confederates may have narrowly agreed to make the experiment but they chickened out when it came to acting on their words.

The measure by the Confederate Federal Congress that was not passed, intended to arm and train enslaved men with no quid pro quo of promise of future manumission; it was merely a measure to arm slaves, no more. There was no mention of this as a first step to citizenship. The measure that DID pass was to allow President Davis, at his discretion, to “raise” up to a certain number of enslaved black soldiers. I believe I have that right?

You can read the bill that passed the Confederate Congress here, as well as the order by Jefferson Davis’ government implementing the bill. The bill made no promise of freedom. But in Davis’ executive order he allowed the recruitment only of slaves who were willing, and whose master was also willing and gave manumission papers to be given to the slaves when their service was complete.

http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/csenlist.htm

That’s correct.

I immensely enjoy your work. I have also read Coates and am following the discussion of his new book. Daniel W. Crofts’s recent work on the original 13th Amendment should be discussed somewhere.

Hi Fred,

Thanks for the kind words. I also highly recommend Lincoln and the Politics of Slavery.