Book Proposal

Forthcoming Fall 2019 at the University of North Carolina Press (Civil War America series)

In the aftermath of the violent murder of nine black Charlestonians at a Bible study at Emmanuel AME Church in June 2015, the South Carolina Division of Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) trotted out the story of brave black Confederate soldiers. They were motivated to do so after photographs were released showing alleged shooter, Dylann Roof, holding or posing alongside Confederate flags. What was already understood as a race crime now turned into a call to lower the Confederate battle flag that had been flying on the State House grounds in Columbia since 1962.

The SCV tried to distance the history and memory of the Confederacy from the events in Charleston with the following press release:

Historical fact shows there were Black Confederate soldiers. These brave men fought in the trenches beside their White brothers, all under the Confederate Battle Flag. This same Flag stands as a memorial to these soldiers on the grounds of the SC Statehouse today. The Sons of Confederate Veterans, a historical honor society, does not delineate which Confederate soldier we will remember or honor. We cherish and revere the memory of all Confederate veterans. None of them, Black or White, shall be forgotten.

Their attempt to save the Confederate flag by claiming that black soldiers fought for the Confederacy failed. A few weeks later the flag was lowered in a brief ceremony and removed to a museum. Their opposition to its removal resulted in a sustained national discussion about the history and legacy of the Confederacy and the place of Confederate iconography in public spaces.

In recent years, Internet stories, textbooks, and even a Harvard professor have insisted that thousands of slaves took up arms and fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. And yet, after close to ten years of research, I have yet to find a single wartime account from a Confederate soldier or civilian demonstrating the presence of black Confederate soldiers in the army before the final weeks of the war in March 1865. Few people appear to be aware of the discrepancy between their own claims about the racial profile of the Confederate soldier and what actual Confederates experienced during the war and remembered long after the war ended. In short, the war that many Americans remember today would be unrecognizable by the very people who fought it.

The black Confederate narrative emerged to perform a specific function beginning in the mid-1970s. Confederate apologists (or neo-Confederates) called up mythical black soldiers to counter the growing acceptance that slavery was the cause of the Civil War; that emancipation was central to what it accomplished; and that former slaves and free blacks were instrumental in bringing about the Confederacy’s demise. However, if free and enslaved black men fought in Confederate ranks, alongside whites, neo-Confederates reasoned, the war could not have been fought to abolish slavery. More importantly, stories and images of armed black men made it easier for the descendants of Confederate soldiers and those who celebrate Confederate heritage to embrace and celebrate their cause unapologetically without running the risk of being viewed as racially insensitive or worse.

It was the era of desegregation, following the civil rights movement that gave us the black Confederate soldier. The very first references surfaced among members of the SCV in response to the popularity of the television series Roots, which aired in 1977. Roots offered the viewing public a sobering look at the horrors of slavery, but it also highlighted emancipation as a central goal of the Civil War and the role that black Union soldiers played in securing that goal, along with the preservation of the Union itself. A small but vocal group of people within the SCV described Roots as a “modern Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and interpreted it as a threat to their own preferred narrative. Violent scenes of slaves being whipped and escaping from their owners undercut the core of the Lost Cause narrative that the SCV continued to hold dear. SCV leadership issued requests to individual chapters to scour family papers and libraries for stories of “SERVICES PERFORMED BY SOUTHERN NEGROES, SLAVE OR FREE, FOR THE CONFEDERACY.” Such calls grew louder as scholars and the public both paid increasing attention to the centrality of slavery and emancipation in the Civil War.

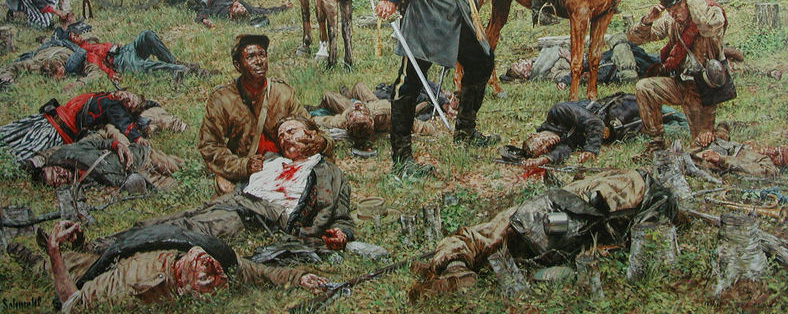

The origins of the black Confederate myth can be found in the war itself. African Americans played critical roles in the war effort between 1861 and 1865, but it was not on the battlefield as soldiers. The Confederate government used African Americans for a wide range of activities to help offset their significant disadvantages with manpower and war materiel. Tens of thousands of slaves were impressed by the government, often against the will of their owners, to help with the construction of earthworks around the cities of Richmond, Petersburg, and Atlanta. Slaves were also assigned to the construction and repair of rail lines and as workers in iron foundries and other factories producing war materiel. In the armies, they worked as teamsters, cooks, and musicians. The vast majority of these men functioned as slaves in the Confederacy’s war effort and not as soldiers.

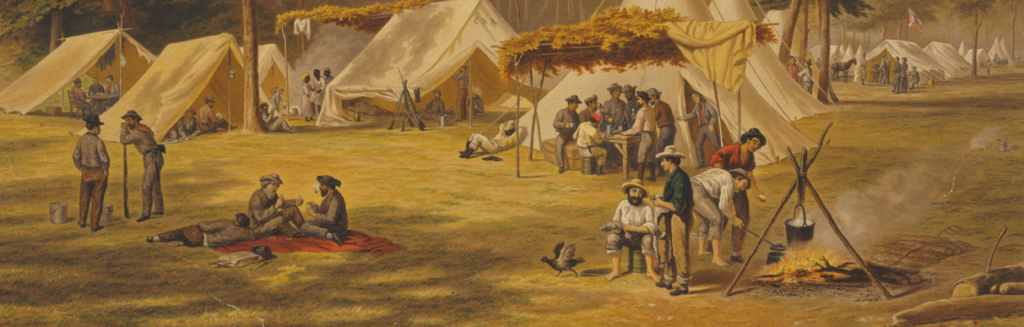

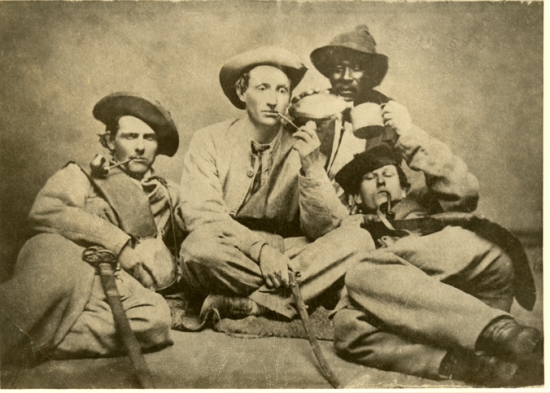

In contrast with this large-scale mobilization of human resources, Confederate officers from the slaveholding class often brought their own slaves from home to serve as “body servants” or “manservants” (who I will call “camp slaves” in order to clarify their legal status). These men served their masters by performing a wide range of tasks related to the maintenance of an efficient campsite. Masters assumed their slaves were loyal to them and to the Confederate cause, which can be seen in their letters and diaries as well as in the photographs taken with uniformed slaves.

Confederate officers expected unquestioned compliance from their slaves as they did back home, but the exigencies of war quickly undermined these assumptions. Camp slaves challenged their master’s authority by pushing for increased privileges in camp such as the ability to earn extra money and right to travel more freely or more directly by running away, especially when in close proximity to the Union army. By the middle of 1863 it was clear to many that the master-slave relationship in camp could not be maintained, as prospects for a Confederate victory grew more precarious.

Officers of Company H (Independent Volunteers) of the 57th Georgia Regiment, Army of Tennessee, 1863.

While it is very likely that a few camp slaves witnessed the battlefield, and may have even picked up a rifle and fired it at a “Yankee,” Confederates never referred to these men as “soldiers” during the war. Even during the very heated debates about whether slaves should be enlisted as soldiers in 1864 and early 1865, Confederates never pointed to camp slaves as evidence that they were already serving in the army. And yet, it is the accounts of these men in particular that have come to shape the modern myth that African Americans fought as soldiers in the Confederate army.

If there is no wartime evidence that African Americans enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate army before the final weeks of the war, then how do we explain the origin of the myth that they did so? Why are some American so attached to stories of loyal black Confederates? Although Confederates assumed the loyalty of the slaves they brought with them into the army, this myth-making took on a new sense of urgency during the years following defeat, as Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line – black and white – jockeyed to control the memory of the war.

Newly freed slaves and black Union soldiers pushed for broad civil rights within a narrative of the war that highlighted their sacrifice for the preservation of the Union and emancipation. For former Confederates, defeat proved devastating. The results of four years of bloody fighting were seen everywhere in the form of ruined cities such as Richmond, Atlanta, and Columbia; the devastated landscapes on which armies struggled for control; and on the faces of shocked veterans and civilians unable to comprehend a future as a people having been forsaken by God.

As a way to cope with military defeat and the end of slavery, ex-Confederates insisted that their slaves had remained fiercely loyal until the bitter end. Accounts of loyal slaves on the home front and in the army reassured white southerners that their cause remained righteous even as they imposed state laws to begin to roll back legislation initiated by the federal government during Reconstruction to assist former slaves.

Reconstruction for white Southerners involved more than rebuilding their economy and regaining control of state governments. In a narrative that came to be called the “Lost Cause,” former Confederates insisted that they had not gone to war to protect slavery, that defeat was the result of overwhelming Northern resources rather than the result of inferior military and civilian leadership, and, most importantly, that their slaves remained loyal to the very end.

Camp slaves became central to this story that white southerners told themselves about their defeat. These men appeared in accounts of Confederate veterans reunions, parades, in the records of soldiers’ homes, and on monuments as well as in countless works of Southern literature, memoirs, newspapers and even in state government records. But in this early postwar period, Lost Causers were careful to distinguish camp slaves from soldiers and most Confederate veterans pushed back vigorously against the suggestion that camp slaves had fought in battles. The Lost Cause highlighted the bravery of the common soldier, who was always white, and their leaders. Conjuring up black soldiers in the ranks neither corroborated the memories of the generation that fought in the war nor did it help to vindicate their cause.

By the end of the nineteenth century, stories of Confederate camp slaves stood side-by-side with popular representations of “Mammy” that many of us remember from Gone With the Wind and “Aunt Jemima” syrup bottles. Memory of camp slaves and other mythical black figures served as a reminder of black loyalty to their masters and the natural order that placed whites at the top of the political and social hierarchy. Accounts of camp slaves rescuing their masters on battlefields or braving enemy fire to bring supplies to the front line extended that loyalty to the Confederate cause itself. Taken together these stories and representations helped to create a mythic past as well as reinforce white supremacy in the Jim Crow South by offering a model of black compliance and submission. At no point, however, were these men depicted as soldiers during this period of Confederate memory production.

The Lost Cause’s emphasis on loyal slaves provides a foundation for the black Confederate myth, but it does not explain its more recent evolution and appeal. For that we need to examine more recent shifts in Civil War memory and the politics of race that followed the civil rights movement.

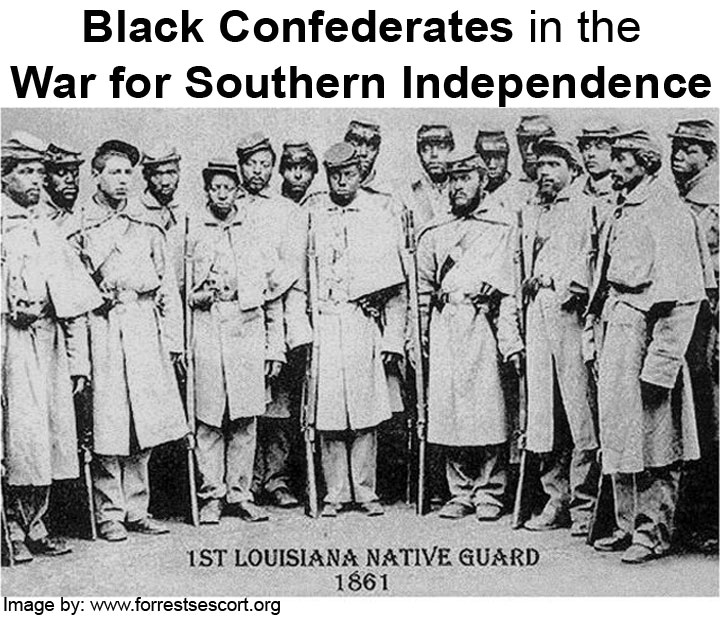

Very little has changed in the basic outline of the black Confederate narrative since the late 1970s, although its reach and influence now extends far beyond that small group of concerned SCV members. Claims made by heritage organizations such as the SCV argue that anywhere between 500 and 100,000 free and enslaved black men fought as soldiers in Confederate armies between 1861 and 1865 even though in fact the government blocked such enlistment until the very end of the war. Most of these arguments employ a hopelessly vague and broad definition of “soldier” that encompasses camp slaves, impressed slaves, and free black men who performed a wide range of functions both in the army and on large-scale military projects such as the construction of earthworks and railroads. Very little attention is paid to the legal status of these men or the coercive nature of the master-slave relationship itself. These arguments also fail to acknowledge the expressed goal of the Confederacy to protect and expand slavery and white supremacy. Rather, many neo-Confederates and others who are misinformed see the mere presence of these men in Confederate ranks as sufficient to consider them soldiers.

Black Confederates now occupy a prominent place in this revisionist story alongside accounts of Asian, Mexican and Jewish Confederates, all of which are intended by proponents of this narrative to appeal to a more racially and ethnically diverse population and to assuage concerns that they harbor racist beliefs. That the Confederate heritage community continues to embrace these stories as a means to counter increasing challenges against the Lost Cause narrative should come as no surprise.

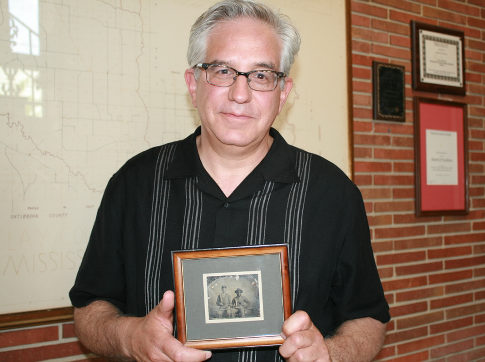

In 2009 Wes Cowan, an appraiser for an Antiques Roadshow, examined a famous tintype from the Civil War. It showed a young Confederate soldier named Andrew Chandler sitting alongside a black man named Silas Chandler. Both Andrew and Silas stare directly at the camera. Both wear Confederate uniforms and are armed. This tintype is one of the most recognizable images from the war, and despite the fact that both men were armed, and in uniform, the evidence points to the fact that Silas was enslaved to the Chandler family. But Cowan mentioned the controversy over whether slaves fought as soldiers in the Confederate army without explaining that Silas was a slave. Instead, Cowan simply noted that it was common for Confederate officers to bring slaves with them into the army as “manservants” and that the Confederate Congress did not authorize the enlistment of slaves into the army as soldiers until the very end of the war.

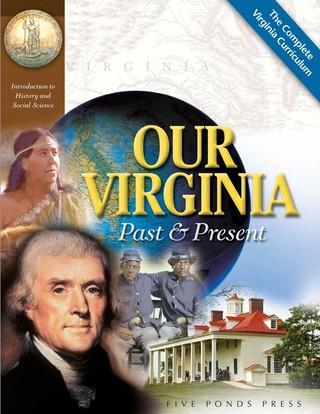

One year after the Antiques Roadshow episode the controversy heated up again, this time over a Virginia history textbook for fourth graders. Not long after the beginning of the school year in 2010, historian Carol Sheriff from William & Mary decided to review the chapter on the Civil War in her daughter’s history textbook: Joy Masoff’s Virginia: Past and Present. Sheriff caught a number of factual errors and questionable interpretations, but one passage in particular caught her attention: “Thousands of Southern Blacks fought in the Confederate ranks, including two battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.” Sheriff wondered how such an outrageous claim could have made it into this book.

The story broke in the Washington Post and was soon picked up by newspapers around the country and beyond. Sheriff herself appeared on MSNBC’s Countdown with Keith Olbermann to discuss the issue. Stonewall Jackson biographer and Virginia Tech professor, James I. Robertson, confirmed that there was no evidence that Stonewall Jackson commanded African American soldiers. In fact, in all of the media’s coverage of this story not one academic or professional Civil War historian came forward to confirm Masoff’s findings or any related claims regarding the presence of black soldiers in the Confederate army. In 2011, the Virginia Department of Education approved a new edition of Masoff’s book without the offending passage.

The story broke in the Washington Post and was soon picked up by newspapers around the country and beyond. Sheriff herself appeared on MSNBC’s Countdown with Keith Olbermann to discuss the issue. Stonewall Jackson biographer and Virginia Tech professor, James I. Robertson, confirmed that there was no evidence that Stonewall Jackson commanded African American soldiers. In fact, in all of the media’s coverage of this story not one academic or professional Civil War historian came forward to confirm Masoff’s findings or any related claims regarding the presence of black soldiers in the Confederate army. In 2011, the Virginia Department of Education approved a new edition of Masoff’s book without the offending passage.

The Masoff controversy revealed a deep gulf between the academic community’s insistence that black men did not fight for the Confederacy and the commitment among some people in the general public to the reality of black Confederate soldiers. And committed they are. A cursory search on the Internet reveals thousands of websites and social media pages devoted to the existence of black Confederate soldiers, many of which are cut and pasted from one another. On their websites, Confederate heritage organizations such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy devote a good deal of online space to stories of brave black soldiers who fought alongside their white comrades. They note that in contrast to the Union army, which eventually recruited black men into segregated regiments after 1863, black men served in Confederate ranks from the beginning of the conflict and in integrated units. Facebook users can join groups such as “The Southern Heritage Preservation Group,” “Black Confederate in the Civil War,” “Black Confederate Historical Resources” and “Save Southern Heritage and History” to reaffirm their beliefs in these stories and stand in defiance of their detractors.

The rise of the Internet occupies a central place in understanding the continued popularity of the myth of black Confederate soldiers. Joy Masoff eventually admitted that much of the research that went into her book was done online through search engine queries with little or no vetting of individual websites – a revelation that raises important questions about how history is increasingly produced and consumed in American culture today. The author’s “research” points to the fact that few people think critically about how to search for reliable information online and how to assess that information.

Between 2011 and 2015 the black Confederate narrative came under sustained attack during the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. Famous battlefields operated by the National Park Service and other historic sites, along with museums across the country, presented the general public with a narrative of the Civil War that directly challenged the foundation on which this narrative rests. In addition, Hollywood films like Lincoln and 12 Years a Slave reached large audiences with dramatic stories about the politics of emancipation and the violence of slavery.

Even if slightly scarred, the black Confederate narrative emerged relatively unscathed and continues to do the work for those individuals committed to a certain memory of the past and politics of the present.

One hundred and fifty years later the American Civil War remains a contested narrative. Searching For Black Confederates peels back layers of history and myth, uncovering the central role that slaves played in the Confederate war effort, the complex relationships forged in the cauldron of war between master and slave, and how the institution unraveled. More importantly, Searching For Black Confederates points to the continued struggle that Americans face in coming to terms with the history and legacy of the Civil War, slavery and racial injustice.

___________________________________________________

Table of Contents

Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Confederate Camp Slaves’ War

- Chapter 2: Confederate Camp Slaves and the Lost Cause

- Chapter 3: Confederate Camp Slaves in Public

- Chapter 4: The Emergence of the Black Union Soldier

- Chapter 5: Black Confederates Go Viral

- Chapter 6: Real Black Confederates

Conclusion

Chapter 1: The Confederate Camp Slaves’ War

In the summer of 1861 Andrew Chandler left West Point, Mississippi with his slave Silas to join the 44th Mississippi Infantry. On the way the two posed for a photograph, which remains controversial to this day. Silas was one of tens of thousands of slaves mobilized to support the Confederate war effort. His presence not only benefited the war effort, but reassured slaveowners like Andrew that they both shared the same goal of Confederate independence.

Slaves like Silas worked in camp, on the march and in battle. Wartime letters and diaries provide intimate details concerning how owners’ attempted to manage their slaves in an environment that differed noticeably from life on the plantation. Slaves tested the boundaries of their legal status most noticeably by earning extra money in camp and even escaping as the armies moved farther from home and in closer proximity to the Union army. By 1863 the relationship between master and slave weakened significantly as a result of the movement of Union armies into the South and the release of the Emancipation Proclamation. Increasing number of escapes forced masters, including Andrew Chandler, to question the loyalty of their slaves. Their actions suggest that the unraveling of slavery occurred within the Confederate army as much as it did on the home front.

Silas remained with the army until the very end of the war. White southerners carefully defined the roles of slaves like Silas from 1861 to 1865 in a way that highlighted the centrality of slavery and white supremacy to the Confederate cause. Not even the reality of defeat could bring Confederates to more quickly embrace the idea of turning slaves into soldiers and possibly salvaging their cause.

Chapter 2: Confederate Camp Slaves and the Lost Cause

Union victory in 1865 left parts of the South devastated and under military occupation. White Southerners struggled to come to terms with defeat, the death of roughly 300,000 young men, military occupation and emancipation. Almost immediately, former Confederates pushed to regain control of their state governments and reassert dominance over freedpeople, who expressed their freedom, in part, at the voting booth and in elected offices.

The Lost Cause narrative of the Civil War arose during Reconstruction as a means to justify secession and explain Confederate defeat. Former Confederates argued that secession was justified as a defense of constitutional right and highlighted the bravery of Confederate soldiers as well as superior generals such as Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. The Lost Cause also assumed a unified Confederate home front and pointed to overwhelming Northern resources as an explanation of defeat. Popular Lost Cause writers such as Thomas Nelson Page asserted that the slave population remained loyal throughout the war. Postwar writers ignored wartime accounts of slave defiance, escape and the return of fugitive slaves fighting for their freedom in Union ranks.

Stories of former camp slaves abound in soldiers’ memoirs and accounts published in newspapers, magazines and publications connected to veterans groups such as the Southern Historical Society Papers and Confederate Veteran. Writers and artists depicted slaves in camp, on the march, and even on the battlefield, though at no point were they confused with soldiers. This postwar literature gave comfort to former Confederates that military defeat and emancipation did not alter the affection that former slaves expressed for their former owners. Memory of loyal slaves, including former camp slaves, helped to assuage the worst fears harbored by former Confederates during the years of military occupation and in the face of an unknown future.

Chapter 3: Confederate Camp Slaves in Public

With the end of Reconstruction and military occupation in 1877, white southerners grew more assertive in their public celebrations of the Confederacy. Cities and towns throughout the former Confederacy hosted reunions that often attracted large audiences. Parades marking the anniversaries of battles and other important events from the war offered opportunities to celebrate the Confederacy and honor the fallen. Monument dedications highlighted themes already engrained in the Lost Cause tradition as they brought together communities, where lessons related to the war were passed down to the next generation.

Former camp slaves, many wearing their old uniforms, played very important roles at public events commemorating the Confederacy. Steve Perry (better known as “Uncle” Steve Eberhart), for example, attended numerous reunions at the turn of the twentieth century, wearing parts of an old uniform that he picked up along the way: a feathered stovepipe hat, brightly-colored sash with U.S. and Confederate flags pinned to his shoulders. He regaled audiences with stories of major battles from First Manassas to Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, though it is unlikely that he witnessed any of these engagements.

The presence of Perry and other former camp slaves at these public events reinforced the Lost Cause claim that they had always been loyal to their masters during the war. More importantly, they reassured the large white crowds that defeat and emancipation did not threaten peaceful race relations. Former Confederate camp slaves, however, took advantage of opportunities to fulfill these expectations within the white power structure. Perry and others played the role of loyal ex-camp slaves for financial gain, in a time when few opportunities were open to elderly African American men. But in the early twentieth century South, he was never confused for a soldier.

A small number of camp slaves, including Perry, took advantage of state pensions that were issued in most of the former Confederate states at the turn of the twentieth century. While these pensions are now often mistakenly interpreted or cited as evidence of service as soldiers, the documents themselves clearly indicate that they were intended for former slaves who could demonstrate faithful service to their masters in camp. These documents offer important insight into the lives of these former slaves, who had to demonstrate loyalty to their former masters and the Confederate cause as part of their applications. Pensions reinforced the expectation that black Americans would remain subservient to the dominant white political hierarchy at a time of racial unrest at the turn of the twentieth century.

Chapter 4: The Emergence of the Black Union Soldier

During the Civil Rights Era historians and black Americans created a counter-narrative that challenged the central tenets of the Lost Cause, especially the unassailable belief in the loyalty of the slave population. They emphasized the central role that slavery played in causing the war and emancipation as its most important outcome. At the center of this new narrative were stories of northern black soldiers and accounts of their role in saving the Union and ending slavery.

During the Civil Rights Era historians and black Americans created a counter-narrative that challenged the central tenets of the Lost Cause, especially the unassailable belief in the loyalty of the slave population. They emphasized the central role that slavery played in causing the war and emancipation as its most important outcome. At the center of this new narrative were stories of northern black soldiers and accounts of their role in saving the Union and ending slavery.

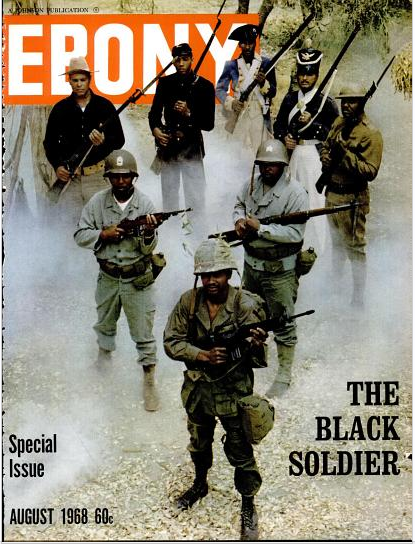

Popular publications such as Jet and Ebony magazine as well as in the literature published by civil rights organizations and public speeches of civil rights activists mobilized the black Union soldier as a reminder of emancipation, freedom and the “unfinished work” of achieving equal rights. It also constituted the first serious volley against the Lost Cause narrative. This was a dramatic shift in popular memory of the Civil War. New scholarship, increased attention to the history of slavery at historic sites and museums, and popular television shows such as Roots brought to bear increased pressure on the Lost Cause narrative and its emphasis on loyal slaves. This new narrative of the Civil War was popularized in the Hollywood movie, Glory (1989) and in Ken Burns’s award-winning PBS documentary, The Civil War (1990).

This rise of the black Union soldier narrative put members of Confederate heritage groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy on the defensive. As emancipation, freedom, and the service of United States Colored Troops increasingly moved to the center of the nation’s Civil War memory, it became more difficult to commemorate the Confederate cause and celebrate Confederate ancestors without having to address the elephant in the room, namely slavery. The first reference to African American fighting as soldiers in the Confederate army quickly followed on the heels of the success of Roots in 1977. A wide range of magazines, newsletters, newspaper articles and books circulated within the Confederate heritage community at this time and was enthusiastically referenced in response to perceived threats against their Confederate ancestors.

Chapter 5: Black Confederates Go Viral

In 1990 a Mississippi chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans placed a “Cross of Honor” in front of Silas Chandler’s gravesite in West Point, Mississippi. This is an honor that is intended for men who served as Confederate soldiers. In doing so, the SCV moved beyond the Lost Cause narrative of the loyal slave and for the first time claimed Silas as a bona fide black soldier. The SCV also solicited the participation of Silas’s descendants as a means to bring legitimacy to their preferred interpretation of his presence in the army – a practice that became more popular during the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

Given the famous tintype of master and slave in 1861, Silas quickly became the face of the black Confederate soldier and with the rise of the Internet this new narrative soon dominated thousands of websites. Today, a Google search for the phrase “black Confederate” will yield over 100,000 results, many of which include references to Andrew and Silas. For casual Internet surfers, the number of hits alone is sufficient proof that significant numbers of black Confederates served as soldiers in Confederate armies. In addition to websites, social media sites such as Facebook and blogs prove that the black Confederate narrative, although it has roots in the Lost Cause era, accelerated in reach and impact during the Age of the Internet.

The famous image of Silas and Andrew Chandler as well as countless others can easily be found on the Internet. Their images are almost always improperly identified and at least one image of a small group of black Union soldiers was at some point intentionally altered to appear as Confederates. In addition to the Antiques Roadshow episode, the story of Silas Chandler has been misinterpreted by the National Park Service, museums, and on National Public Radio programs. T-shirts depicting Silas and Andrew as soldiers designed by Dixie Outfitters and children’s books attest to their popularity in certain circles.

Numerous stories about Silas and Andrew that are unsupported by any wartime evidence now circulate freely on the Internet. The spread of this narrative and how myths are disseminated raises important questions about how history is now produced and consumed online.

Chapter 6: Real Black Confederates

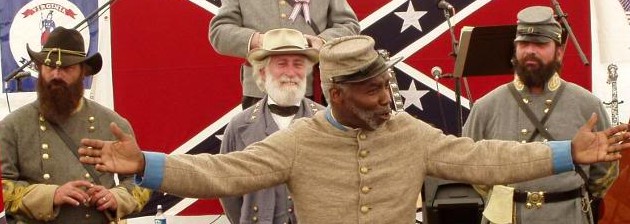

From 2011 to 2015, the black Confederate narrative flourished, as a counter-argument to the public events during the Civil War Sesquicentennial, and their attention to slavery, emancipation and the service of United States Colored Troops. Confederate heritage organizations moved beyond their websites to more directly acknowledge black Confederate soldiers in public places. Increased calls to establish monuments and other markers to black Confederates echoed in response to the shootings in Charleston and the push to remove Confederate flags and monuments from public spaces. The SCV continued to honor former slaves (now soldiers) with elaborate ceremonies that included the dedication of military-style grave markers as well as the presence of the descendants of former slaves and a small, but vocal group of black Americans, who embrace the black Confederate narrative. Many of these events garnered local and sometimes national media attention. These stories often go unchallenged by reporters, who fail to consult with historians to verify the relevant history.

One of the most vocal supporters is H.K. Edgerton. In 2002, Edgerton, a former chapter president of the NAACP in North Carolina, walked from North Carolina to Texas wearing a Confederate uniform and carrying a battle flag. He is one of a small group of African Americans who identify strongly with Confederate iconography and its cause. Edgerton sees himself as a living reminder of the thousands of African Americans who supported the Confederate war effort on the plantation and in the ranks as soldiers. Like Steve Perry before him, Edgerton remains a popular presence at Confederate heritage events sponsored by the SCV and other organizations, which almost always include an emotional reading of the poem, “I Am Their Flag.” Edgerton’s presence vindicates the views of the large white crowds in attendance, and suggests that the black Confederate narrative is sufficiently malleable to accommodate what on the surface appear to be strange bedfellows.

African Americans are featured in these ceremonies to bolster the claims made about black military service and the Confederacy as a whole. Many of them identify with the Conservative politics that is often expressed at these events, while others are attracted to an alternative narrative to that of slavery that transcends the history of racial violence in the South. The participation of H.K. Edgerton in North Carolina, Anthony Hervey in Mississippi, and Karen Cooper in Virginia in these events offers a window into the intersection of historical memory and the politics of race at a time of increased racial tension.

Anticipated Market

This will be the first book-length study of the history of Confederate camp slaves and the myth of the black Confederate soldier.

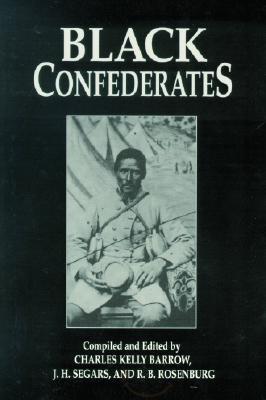

It will counter the arguments in books published by small novelty presses that cater specifically to Confederate Heritage groups such as Pelican Press. Black Confederates (2004) and Black Southerners in Confederate Armies (2001), for example were both edited by Charles Kelly Barrow, who is the current Commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Pelican’s most popular title, The South Was Right! offers one of the most vigorous defenses of this myth. Other examples include Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man’s Friend by Richard Williams (Cumberland House, 2006), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War by H.W. Crocker III (Regnery, 2008), Everything You Were Taught About the Civil War is Wrong, Ask a Southerner by Lochlainn Seabrook (Sea Raven Press, 2010) and most recently, Al Arnold’s Robert E. Lee’s Orderly: A Modern Black Man’s Confederate Journey (Publish Green, 2015).

It will counter the arguments in books published by small novelty presses that cater specifically to Confederate Heritage groups such as Pelican Press. Black Confederates (2004) and Black Southerners in Confederate Armies (2001), for example were both edited by Charles Kelly Barrow, who is the current Commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Pelican’s most popular title, The South Was Right! offers one of the most vigorous defenses of this myth. Other examples include Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man’s Friend by Richard Williams (Cumberland House, 2006), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War by H.W. Crocker III (Regnery, 2008), Everything You Were Taught About the Civil War is Wrong, Ask a Southerner by Lochlainn Seabrook (Sea Raven Press, 2010) and most recently, Al Arnold’s Robert E. Lee’s Orderly: A Modern Black Man’s Confederate Journey (Publish Green, 2015).

Books in this camp occupy a small place in a much larger body of literature that works to promote a Lost Cause narrative of the war, with an emphasis on slavery as a benign institution and race relations as positive. It is likely that many in this community will be dismissive of Searching For Black Confederates, but I also anticipate a certain level of engagement from True Believers, if only in an attempt to challenge its central claims. I welcome this kind of scrutiny and expect that there will be opportunities to engage individuals and organizations in a productive manner.

Searching For Black Confederates will also add to a growing field of academic scholarship on the role of slaves in the Confederate army and the broader war effort. Historians such as J. Tracy Power and Joseph Glatthaar have touched on the presence and function of Confederate camp slaves in camp, on the march and in battle. Colin Woodward’s recent study, Marching Masters (University of Virginia Press, 2014) includes an entire chapter on camp slaves and has proved to be very helpful in framing my own questions. Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning (Harvard University Press, 2010) and especially Jaime Martinez’s Confederate Slave Impressment in the Upper South (University of North Carolina Press, 2013) explores the relationship between the Confederate government and slave owners and the many wartime projects that demanded slave labor. The debate within the Confederacy to arm slaves toward the end of the war is thoroughly covered in Bruce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation (Oxford University Press, 2006). This book should also find a home in a growing body of scholarship devoted to Civil War memory as it intersects with a number of topics that have been researched over the past decade, most notably by David Blight in his book, Race and Reunion (Harvard University Press, 2002).

While I hope to add to this scholarship, the narrative style, chronological sweep, and pace of Searching For Black Confederates is geared primarily for a popular audience with an interest in the Civil War, the history of race, and the complex ways in which Americans continue to struggle to come to terms with its legacy.

The Author

I have spent close to ten years researching and writing about Confederate camp slaves and the myth of the black Confederate soldier, and am well prepared to complete this book project. The subject of black Confederates remains the most popular subject of discussion on my blog, Civil War Memory, which I have authored for over a decade. Individual posts almost always lead to vigorous debates that over time have resulted in thousands of comments. The blog has attracted thousands of subscribers and includes many of the top scholars in the field, some of the most hard line Confederate apologists, and a wide range of Civil War enthusiasts, who are curious about the subject and want to learn more.

The research for this project has taken me to numerous archives, including the Virginia Historical Society, Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Georgia Historical Society, Tennessee Historical Society, Boston Athenaeum, Mississippi State Archives and The National Archives.

This project builds on my interest in the Civil War and race in American memory, which I explored in my first book, Remembering The Battle of the Crater: War as Murder (University Press of Kentucky, 2012) and other publications.

My articles on this subject have appeared in The New York Times, the Atlantic, The Daily Beast as well as in academic journals and popular magazines. I have lectured on the subject at numerous Civil War Roundtables, the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, the National Civil War Museum and at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. In addition, I have appeared as a guest to talk about the Civil War and black Confederates on NPR’s The Takeaway, Studio 360 and Tell Me More with Michel Martin. Ta-Nehisi Coates at the Atlantic, Adam Serwer at BuzzFeed, and Clay Risen at The New York Times have all cited my research on the subject of black Confederates.

Given the amount of attention that this myth has received over the past twenty years, and will likely continue to receive for the foreseeable future, I am convinced that a book-length exploration is warranted. Rarely do historians have the opportunity to fill such a gaping hole in a field of history, but it is even more unusual to have the opportunity to shape the public discussion about a subject misunderstood as the history and memory of slavery.