I am working to finish up an essay on Robert E. Lee’s Arlington House for a collection of essays on Southern Tourism edited by Karen Cox. The tentative title is, “The Robert E. Lee Memorial: A Conflict of Interpretation”. My research on this subject has taken a couple of turns since I agreed to be a contributor to the project. It started out with a focus on slavery, but I am now looking more broadly at how various parties debated over how to interpret the home as part of Arlington National Cemetery. Much of my focus is on the 1920s and 1930s and the long-term consequences of what took place during that time. What follows is a very rough introduction to the essay that hopefully provides a taste of where I am going with this. Comments are welcome, especially those that are critical.

I am working to finish up an essay on Robert E. Lee’s Arlington House for a collection of essays on Southern Tourism edited by Karen Cox. The tentative title is, “The Robert E. Lee Memorial: A Conflict of Interpretation”. My research on this subject has taken a couple of turns since I agreed to be a contributor to the project. It started out with a focus on slavery, but I am now looking more broadly at how various parties debated over how to interpret the home as part of Arlington National Cemetery. Much of my focus is on the 1920s and 1930s and the long-term consequences of what took place during that time. What follows is a very rough introduction to the essay that hopefully provides a taste of where I am going with this. Comments are welcome, especially those that are critical.

In her epistolary novel, A Romance of Arlington House, Sara Ann Reed imagines a young couple on an afternoon excursion across the Potomac River to visit the grounds at Arlington some time in the 1870s. On the way they engage in polite conversation about the history of the home and the surrounding grounds. A young Virginia listens intently as her dashing military escort and Civil War veteran shares the history of the home, including its association with the Custis family, its abandonment by the Lee family on the eve of civil war, and its transformation into a Union camp and eventually as a final resting place for fallen soldiers. As the carriage makes its way along the aqueduct and in full view of Arlington, the young officer compliments George Washington Custis for the design of the home as well as its overall “beauty of situation.” Virginia agrees with her escort’s assessment, but suggests that the home “ought to have been kept for his descendants, and not desecrated by being made a burial place.” Perhaps not fully realizing how a veteran would interpret such a comment, Virginia may have been surprised by her escort’s response and “piercing glance”: “Why I might think that I have a Southern woman beside me. How can you, a loyal Unionist call ground desecrated because it holds the sacred dust of men who gave their lives that you might have a country that is fast becoming one of the foremost nation’s of the world?” Virginia’s expression of “sympathy with the Lee’s” only serves to antagonize her companion even further. With an air of frustration, the officer justifies the transfer of the property based on the family’s “delinquent taxes” as well as a belief that “Mr. Custis would rather the home he was so proud of should be national property, than to have it in the hands that had borne arms against his country, even though they were those of his own grandchildren.” Rather than continue their discussion of “right and wrong” and run the risk of it ruining what began as a pleasant afternoon trip, the couple decides to focus on more polite subjects as the carriage moves ever closer to their destination.

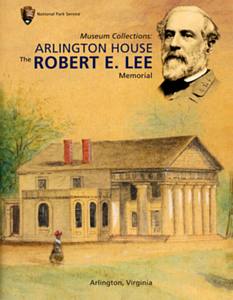

This fictional account set in the 1870s over who was entitled to legal ownership of Arlington House continued to resonate at the time of the book’s publication in 1908. Although the issue of legal title had been settled in 1882, questions remained over how to interpret the home within the context of the surrounding landscape. Various agencies of the federal government, including the War Department and Department of Interior debated throughout the first few decades of the twentieth century concerning who should have jurisdiction over the home. Even more problematic were questions surrounding how the home itself ought to be interpreted and presented to the general public. A number of interpretive themes were recommended at this time, including the turning of the home into a shrine and museum to George Washington – part of Custis’s original vision for the estate. Others hoped to return the home to a condition reminiscent of a time during the Custis family’s ownership. Finally, the success of sectional reunion in the wake of the Spanish-American War led to calls to restructure the home to reflect ownership by the Lee family on the eve of the Civil War. These competing visions for the property were vigorously debated, as part of a larger concern over how the home ought to fit into the broader landscape of Arlington Cemetery, which had become widely regarded by many across the nation and a growing number of tourists as sacred ground.

Although the National Park Service now maintains Arlington House as the Robert E. Lee Memorial, and most interested Americans connect the property with the famous Confederate Chieftain, this designation was not inevitable in the early part of the twentieth century. Understanding how this transformation occurred sheds light on the contested nature of historic and cultural sites as various groups competed to impose their preferred interpretation on historic landscapes and shape our collective memory of the Civil War. Like other Civil War sites, Arlington became the scene of vigorous debate during the early twentieth century not simply because the site included the pre-war home of Robert E. Lee, but because that home was located on ground designated as a final resting place for fallen Union soldiers. Depending on how these two focal points were interpreted and/or remembered potentially left the landscape with multiple and even contradictory meanings. For the most part, these debates have been conducted away from the curious eyes of the many Americans who have visited Arlington over the past 100 years. The experiences of these visitors as well as the meanings and lessons they take home from this particular place, however, continue to be shaped by the decisions made as a result of these previous and ongoing debates.

Mine is the only essay dealing with Arlington. You've hit on a number of important points that worked to shape the early history of Arlington. The circumstances surrounding the death of young Meigs is indeed controversial, but no doubt contributed to a fairly strong push to have the cemetery overshadow any remembrance of the Lee family. It is also interesting how the burials of Sheridan and other high-ranking commanders within a few yards of the mansion contributed to this during the 1880s and 1890s. By the early 20th Century bushes had been placed around those graves to shield them from the view from the house. The whole postwar story is quite fascinating.

Kevin-Especially in light of that passage from the Reed novel, I hope someone is dealing with the role that the death of the young Brevet Major. buried in Section 1 of the National Cemetery, played in the placement of the cemetery on Arlington grounds. the actual circumstances of his death will always be controversial, but his father and many others in the Union Army, were convinced that the Major (Bvt) was murdered in cold blood by civilians or partisans in civilian clothes. Unfortunately for the Lees, the young man, as you know was John Rodgers Meigs and his devoted and devastated father was Montgomery Meigs. There is no doubt that the placement of the cemetery on Arlington grounds to make it impossible for the Lees to ever be able to live there again was very much revenge by a grieving father.

As I understand it, Montgomery Meigs was a Georgian by birth, who was raised from childhood in Pennsylvania. He ran afoul of John B. Floyd when the latter was Buchanan's Secy. of War & really was banished to the Dry Tortugas. Is there record, specifically of Gen. Meigs' attitude, before his son's death, towards those southerners who went with the Confederate army after receiving an education and career from the US government and taking an oath to support and defend the US Constitution?

I think the Meigs angle (The retaliation after John Meigs' death also resulted in the “Burnt District” in Virginia) brings in something that is very easy to lose in the beauty and peace of Arlington House-the hatred, rage and bitterness that can burn at their most intense in a civil war due to the very fact that such a war cuts across family lines, professional lines (although, in many ways, the tiny antebellum US army officer corps was a family, especially the West Point alumni, with biological and marital ties as well) with the former friends and relatives on either side of the divide regarding each other not merely as enemies but as traitors.

The slavery history is very important. That lovely and genteel lifestyle came at a terrible price for others. But I also think that George Washington Parke Custis needs to be seen as not just the builder of it but his attitude towards slavery needs to come forward as well. Lee often gets credit for freeing “his” slaves immediately before the war. They weren't Lee's slaves and never were. Lee was acting as executor of his father-in-law's will in freeing G.W.P. Custis's slaves. Lee may deserve a few points for not trying to have that portion of the will invalidated. That was quite common and the courts were very sympathetic to distressed heirs who saw dear deceased daddy (who the heirs would convince themselves was not quite right in the head when the will was made) trying to strip the estate of its prime assets. However, it was Custis, who worshipped the step-grandfather who raised him, who was determined to follow the precedent of Washington's will. Custis's will required that all 200 of the slaves he owned (he wasn't a very good manager but this made him a major slaveholder) be freed once the estate's other bequests were paid or five years after his death, whichever came first.

Kevin-Especially in light of that passage from the Reed novel, I hope someone is dealing with the role that the death of the young Brevet Major. buried in Section 1 of the National Cemetery, played in the placement of the cemetery on Arlington grounds. the actual circumstances of his death will always be controversial, but his father and many others in the Union Army, were convinced that the Major (Bvt) was murdered in cold blood by civilians or partisans in civilian clothes. Unfortunately for the Lees, the young man, as you know was John Rodgers Meigs and his devoted and devastated father was Montgomery Meigs. There is no doubt that the placement of the cemetery on Arlington grounds to make it impossible for the Lees to ever be able to live there again was very much revenge by a grieving father.

As I understand it, Montgomery Meigs was a Georgian by birth, who was raised from childhood in Pennsylvania. He ran afoul of John B. Floyd when the latter was Buchanan's Secy. of War & really was banished to the Dry Tortugas. Is there record, specifically of Gen. Meigs' attitude, before his son's death, towards those southerners who went with the Confederate army after receiving an education and career from the US government and taking an oath to support and defend the US Constitution?

I think the Meigs angle (The retaliation after John Meigs' death also resulted in the “Burnt District” in Virginia) brings in something that is very easy to lose in the beauty and peace of Arlington House-the hatred, rage and bitterness that can burn at their most intense in a civil war due to the very fact that such a war cuts across family lines, professional lines (although, in many ways, the tiny antebellum US army officer corps was a family, especially the West Point alumni, with biological and marital ties as well) with the former friends and relatives on either side of the divide regarding each other not merely as enemies but as traitors.

The slavery history is very important. That lovely and genteel lifestyle came at a terrible price for others. But I also think that George Washington Parke Custis needs to be seen as not just the builder of it but his attitude towards slavery needs to come forward as well. Lee often gets credit for freeing “his” slaves immediately before the war. They weren't Lee's slaves and never were. Lee was acting as executor of his father-in-law's will in freeing G.W.P. Custis's slaves. Lee may deserve a few points for not trying to have that portion of the will invalidated. That was quite common and the courts were very sympathetic to distressed heirs who saw dear deceased daddy (who the heirs would convince themselves was not quite right in the head when the will was made) trying to strip the estate of its prime assets. However, it was Custis, who worshipped the step-grandfather who raised him, who was determined to follow the precedent of Washington's will. Custis's will required that all 200 of the slaves he owned (he wasn't a very good manager but this made him a major slaveholder) be freed once the estate's other bequests were paid or five years after his death, whichever came first.

Mine is the only essay dealing with Arlington. You've hit on a number of important points that worked to shape the early history of Arlington. The circumstances surrounding the death of young Meigs is indeed controversial, but no doubt contributed to a fairly strong push to have the cemetery overshadow any remembrance of the Lee family. It is also interesting how the burials of Sheridan and other high-ranking commanders within a few yards of the mansion contributed to this during the 1880s and 1890s. By the early 20th Century bushes had been placed around those graves to shield them from the view from the house. The whole postwar story is quite fascinating.