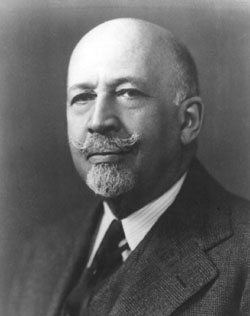

My American Studies course is currently making its way through Reconstruction as part of a broader look at the history of race. From here we move on to the twentieth century and the Civil Rights Movement. Reconstruction readings include Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B. Dubois. For our Dubois selection we decided to read his 1943 essay in the journal, PHYLON, titled, “Reconstruction, Seventy-Five Years After.” It allowed the class to make connections between the three authors’ views of Reconstruction as well as the racial context of WWII. Analogies between the Civil War and Nazi Germany come up fairly frequently on this blog and others, but our tendency is to resist the urge given the strong emotions that they engender as well as the sloppiness that almost always frames the discussion.

On the other hand, here we have an African American looking back on the history of the Civil War in the middle of WWII. Dubois can’t help but make the connection in the process of reminding his readers just how crucial African Americans proved to be in preserving the Union:

We are today contemplating with uncertainty and fear the steps that must be taken in Germany by the victorious allies after the overthrow of Hitlerism. Suppose it were true that the only way to restore Germany in a form which would make it impossible for her to be for a generation if not forever, a menace to the peace of the world, was to put political and social power into the hands of a mass of people who had long been victims of German oppression and who now desired freedom, work, land and education? Suppose that when the Allies marched into Germany, they found thirty-five per cent of the population, friendly and sympathetic, but hated by the Germans as the Jews are hated; and in contrast to the Jews, ignorant, poor and sick, because of slavery and exploitation for two hundred and fifty years; would there be the slightest doubt but that this suffering and oppressed people would be fixed upon by the conquerers as the God-sent instrument for the reconstruction and democratization of Germany? ….

And what is true in the South faces the nation in this Second World War. No matter what we may think and say of Germany, by singular paradox the race-religion which Germany has suddenly thrust to the front, is but an interpretation of what America and Europe have practiced against the colored peoples of the world. No matter who wins this war it is going to end with the question of the equal humanity of black, brown, yellow and white people, thrust firmly to the front. Is this a world where its peoples in mutual helpfulness and mutual respect can live and work; or will it be a world in the future as in the past, where white Europe and white America must rule “niggers”? The problem of the reconstruction of the United States, 1876, is the problem of the reconstruction of the world in 1943.

It should be remembered that Dubois wrote this before the liberation of the Concentration Camps in 1944-45. I actually think that this helps to strengthen rather than weaken his analysis.

I have seen photographs in a book about the KKK of joint meetings with the German-American Bund.

https://medium.com/race-class/12a3018d5abc

The lesson of the Holocaust didn’t end when the last concentration camp was liberated. Jews fled Europe en masse. Going to Israel, the US, etc. This has given the generation of victims and criminals time to die off and their offspring have displaced them. This “resting period” has resulted in the new generations being able to talk with and in some ways, to reconcile their ancestor’s history. There are actually some Jews choosing to move to Berlin. African Americas were denied this resting period. The descendants of masters and slaves have not had this time to heal. Each generation passes down its own bitterness. No white person wants to be constantly reminded that his ancestors were responsible for such an atrocity, as though guilt and shame can be a legitimate inheritance. No black person is ever allowed to forget or forgive the suffering because there’s an unbroken chain of vilification being handed down within the black community over slavery from one generation to the next. Until that chain is broken, nothing will change.

The resonances between 1933-1945 and 1861-1865 are many and complex – and whilst Jewish Americans have often trail-blazed at the forefront of progressive social movements in the 20th century and this image has great popular traction – there was a lively Jewish presence in the Southern states in the early 19th century and who remained loyal to the south after secession. This excellent article from NYT Disunion outlines some of this fascinating lesser known story of the civil war

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/17/passover-in-the-confederacy/?_php=true&_type=blogs&smid=li-share&_r=0

extract:

For many American Jews today, particularly those descended from immigrants coming through Northeast corridors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that Confederate Jews fought on the side of slavery offends their entire worldview, rooted so deeply in social justice. Even the idea of there being so many Jews in the American South, decades before Ellis Island opened its gates, is a strange idea

see also

http://www.jewish-history.com/civilwar/prayer.htm

http://www.jewish-history.com/civilwar/seder.html

– This is a point of difference between the Confederate years of 1861-1865 and the various organisations/manifestations of the KKK – whose Anti-Semitism was never hidden in the 20th century. Indeed the Anti-Semitism of the KKK would have been totally familiar to Dubois and may have been one of the catalysts of the types of analogies that Dubois was making.

Complicating the Nazi = Confederate construct (which I think is a problematic rhetoric) one could add a further irony to this mix: the virulent Anti-Semitism of the Nation of Islam and some similar groups that matches that of some white power groups

Dubois’ article is an excellent catalyst itself for jump-starting discussion on WW2, the holocaust, reconstruction as well as the ACW – but in thinking of the teaching of Holocaust memory especially in German schools and then how it has catalysed the teaching of colonialism, and increasingly also the ACW, one could easily lose the core thread and it strays into area where I cannot lay hands on appropriate sources – I will just drop in the comment that I have read somewhere whilst spies and intelligence agencies were supplying the allies with accounts of concentration camps during the 1940s, including the “death camps” in Poland, there was some reluctance to believe these reports due to the British press concocting and publishing many exaggerated horror stories such as the German soap factory that rendered down soldiers’ corpses “harvested” from the battlefields during world war 1 –

“Allowed?” Why wouldn’t DuBois be entitled to freedom of speech?

Is that how you interpreted the post title? Hmmmm.

A couple of comments on the discussion. It’s pretty clear to me that the DuBois quote is referring to what an occupying power trying to establish a democratic order in an occupied country would need to do. DuBois understood Reconstruction to be just that. (His concept of it as a virtuous democratic dictatorship is a separate issue, but that wasn’t part of the quote you give.) The Reconstruction period is still studied by experts in counter-insurgency for possible lessons for today. Although I’d have to say that what I’ve seen of that work isn’t too impressive in analyzing the Reconstruction period. DuBois’ comparison, on the other hand, seems perfectly sensible on its face.

The German Autobahn (highway system) was planned under the Weimar Republic and was a real project, not a “Potemkin Village” project. The only thing I would add is that Hitler and his regime understood the Autobahn primarily in *military* terms, as infrastructure to facilitate future wars. In his first Cabinet meeting, he directed that all projects (including the Autobahn) be considered in the first place for their usefulness in war. The Autobahn is only a net positive aspect of the Hitler regime if you extract it from the broader policy, which lead to the new world war that was in the end disastrous for Germany.

Yes you are correct about the reference, Justin. However, please see Strangers in the land: Blacks, Jews, post-Holocaust America By Eric J. Sundquist: (Google Books) where examples such as Klan Raids and some of the other references to genocide coincide with Lemkin’s definition of genocide. I also recall the syphilis experiment on 400 African Americans who were caught unaware. My point being, that we should be careful not to minimize the effects of slavery and the terrors of Reconstruction.

African Americans were less important to former slave owners after 1865, and according to their own testimonies, suffered even more brutally then. I believe your reference to the word “genocide” above does correctly depict events endured perhaps not in the use of the word today but definitely in the origin of its use. At least this would be the case for the countless individuals who lost their lives on the first slave ships to the last hanging.

Robin, that is the tragedy of the Civil War, not necessarily that the African Americans were “less important to the former slave owners” but that the African Americans had become the focused “cause” of their financial ruin. Had emancipation been gradual and compensated, as had been achieved elsewhere in the world, the viciousness would not have manifest itself as it did. This is not to say that prejudice and bigotry would not have existed, but it would be hard to imagine the violence without the misplaced “justification” in the minds of the former slave masters. It is human nature to seek a scapegoat and the Civil War created that situation, very tragically.

That’s an interesting definition of genocide, that can be applied to the detruction of African culture in the enslaved people of America, and the subsequent assault on developing a functional culture by African Americans.

However when we say genocide in this context, what we mean is the actual killing of every single member of the targeted group, from the most elderly to infants. It’s just different.

Kevin,

Where du Bois is right is that WWII was a hammer blow to racism, regardless to how many white supremacists were on the Allied side. Where he is wrong is that conditions in Reconstruction America and postwar Germany resembled each other and could be usefully compared.

Michaela,

Your excellent post reminds me that Mussolini, in fact, didn’t make the trains run on time.

Hi Matt,

Thanks for the response. I tend to agree with you that there isn’t much of a comparison to work with. At the same time I think it’s important to look at this from DuBois’s perspective. Seventy five years after Reconstruction and the United States is engaged in another war for freedom and yet African Americans don’t enjoy basic civil rights here. On top of that thousands of African Americans are taking part in both the Pacific and European theaters of war. I do think that his final point is relevant in suggesting that the fundamental question at stake is one of racial supremacy.

We must be careful to consider the original definition of genocide as it was coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1943. See Raphael Lemkin’s Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation – Analysis of Government – Proposals for Redress, (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944), p. 79 – 95.

“New conceptions require new terms. By “genocide” we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homocide, infanticide, etc.(1) Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.”

Dr. W. E. DuBois’ use of the word “genocide,” (coined in 1943) in 1943 accurately describes the evils suffered by enslaved African Americans and the effects of which are yet felt today. A sincere appreciation for the destructive influences of slavery in the areas specific to culture, national feelings, religion, personal security, liberty, health, dignity, etc. can serve as a great healing balm and door opener to greater self awareness.

Robin, I am not finding DuBois’ use of the word “genocide” anywhere in his article of 1943. Perhaps the search feature in JSTOR is incorrect. Could you please point it out?

You won’t find it mentioned in this particular essay.

Thanks Kevin. Did DuBois apply the word “genocide” in any other discussion of American slavery?

Justin,

Not that I know of, but than again, I haven’t read through the entire DuBois library.

Kevin, upon further search (yes, on the internet, sorry), I have found a 1951 petition against the government for inaction on lynching titled “We Charge Genocide”, and it does quote the United Nations definition which had broadened the application to “Any intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, racial, or religious group…”.

I still can’t see this as valid regarding American slavery itself where the intent was not to kill the enslaved but to promote their higher productivity and profitability.

Thanks for the reference.

Thanks for the reference on the term. I’ve never looked into the origin of the word.

His admiration for Nazi germany was more for the economic achievements such as new roads etc.

Is this a reference perhaps to what was known as the Autobahn? My understanding is that the Autobahn was a Nazi project, but largely a “Potemkin Village” propaganda effort to get the masses on board with fascism rather than a real attempt to revolutionize transportation within Germany. It was something the Nazis could claim they would have built if all of their manpower and material resources hadn’t been so quickly diverted to the war effort.

Craig,

Please see my wife’s comment.

I think where the concentration camps came into the general discussion is the impact they had on soldiers, including the black ones, who liberated those camps. I’ve read some on their reaction. It wasn’t a comparison of past racism in the US in general or in the South in particular to genocide/the Holocaust but a realization of this being where racism, if allowed respectability and permitted to flourish, can lead. I doubt that, before the Nazis, anyone would have believed that Germany, known for its culture and learning, would be capable of perpetrating anything like the Holocaust. Anti-semitism had long been rampant in German society but, nevertheless, the German Jewish community before the Nazis gained control of the German government were considered to be one of the most thoroughly assimilated Jewish communities in Europe. Many whom the Nazis identified as Jews did not really see themselves as such or, at most, in the cultural, rather than the religious, sense. All of that counted for nothing under the Nazis.

The distinction has to be made that DuBois is not comparing the then unknown mass extermination of Jews to the former American system of slavery and continued bigotry. He is contrasting the need to deal with a post war era of the eventual victors over the conquered. A well anticipated “reconstruction period”. He does perceive the Jews as being the oppressed population that should rule the defeated purveyors of a “race-religion” in Germany. There is his comparison only, the post Civil War installment of former slaves as the legislators of the former slave states.

The slave south was not a “genocidal state”. Although maintaining an attitude of racial superiority (which reigned globally as DuBois does point out), at no time was the goal of the Confederate government to eradicate the black race from the world. Since 1619 slaves in America had been bought, sold and used as a valuable commodity and enthusiastically encouraged to propagate. There certainly was cruelty, as is endemic to any system of servitude (compare even men over women and adults over children, etc.), but at no time was there an objective to destroy the African slaves by the antebellum south or the Confederate government.

What DuBois is pointing out was the need for “equal humanity” for all races, and the need to quell “for a generation if not forever, a menace to the peace of the world”, as was done here from the end of the Civil War to 1877, by installing the formerly oppressed into the position of power.

And with that the comparison ends. His premise could be just as equally applied to any post-war situation.

I think that is exactly what DuBois is saying. He’s not comparing the way in which they were dealt with as much as he is anticipating what will follow.

By “allowed” of course. If it’s a good idea, I don’t think so. The fact he wrote without knowing about the death camps makes his analysis irrelevant, since he was missing key information about the Nazi project. If Du Bois were to revisit this essay in the light of that information, I’m sure he would amend his essay.

Thanks for the comment, Matt. In what way would he have to revise his thinking? It seems to me the death camp would only help to reinforce his argument.

Dubois’ statement needs a lot of context, which you provided. Making a comparison with anything related to Nazi Germany is tough, because it is toxic with overzealous condemnation (not that it is undeserved!). It makes it tough for people to draw rational comparisons between Nazi Germany and anything else. For example, regardless of how it true it may be, few vegetarians would not be offended if I pointed out that Hitler was one of them.

Regardless, I do not think anyone can or should prevent a historian from making the comparison. I would be curious if Dubois made similar comments post-1945.

It is interesting to note that Dubois was an early admirer of Nazi Germany. This was in the 1930’s. In the end he opted for another utopian totalitarian ideaolgy, ending his years as an avowed Marxist Leninist.

Ted,

You are going to have to explain what you mean by “admirer”. DuBois visited Germany in 1936 and did comment that he was treated better by the academic community compared to his experience at home. On his return home he expressed serious misgivings concerning the mistreatment of Jews. David Levering Lewis goes into this in a great deal of detail. Lewis considers the possibility that DuBois may have drawn a distinction early on between the situation of the German Jews and African Americans during the time he spent studying in Germany between 1892 and 1894.

Yes he was critical of Nazi antisemitism. His admiration for Nazi germany was more for the economic achievements such as new roads etc. He was very much a Deutschphile, but this dated back his two years as a student in the 1890’s. Imperial Germany seems to have welcomed students of all races to come study there. Another person of color and revolutionary thinker to do so was Filipino national hero Jose Rizal.

According to my German wife, the roads were pre-Nazi. I tend to agree with you that his love for Germany came from his time spent there as a student.

Thank you Sire.

Thanks, Kevin for listening: )

This is actually an argument that Germans held on to until the 60s when this kind of rewriting history became less possible, last but not least due to the intellectual revolts at the universities. The origin of the road system can be found in the Weimar Republic. And that information is neither hard to get to nor controversial.

Regarding the “then unknown” fact of the death camps and the mass murder organized by the German government under Hitler: It is another perpetuated myth that the mass murder and torture in and outside of death camps of Jews as well as so called enemies of the state in National Socialist Germany was unknown to most Germans, or by the late 30s, the European neighbors and international community overseas. That a baker in Munich or a dentist’s daughter in Kansas might not have known about it does not make it unknown. Some Americans still don’t even know where Iraq is. That does not make it an “unknown” fact that the cause of the recent Iraq war was at best controversial.

It is even more disturbing to me to read this when I sat in my German high school history class 24 years ago discussing this well kept myth that we then already analyzed as serving to rewrite history and give contemporaries of the holocaust a free ticket to “well deserved” ignorance: ” we didn’t do anything because we just didn’t know…”. Contemporaries in and outside Germany. It stems from a postwar Germany that in the 50s wanted to live like the three monkeys to forget the horrors that happened among them and because of them. And it stems from the allies that wanted to clean their hands that they didn’t do anything before the “surprising” opening of the camps because they didn’t know. And out of this time these lies have become today’s “well known facts”.

I know this is not what your post was about, Kevin, but Civil War Memory has a lot in common with Holocaust Memory. In both I see stereotypes that have formed our collective “mis” memory of the American slave owning society and Holocaust and postwar Germany.

For the most contemporary sources read Sophie Scholl, read Erich Kaestner’s Notabene 45 and Bonhoeffer. Read report of international delegates visiting Theresienstadt in 1943 and watching a staged soccer game to be convinced that inmates of camps were treated “right” according to Red Cross guide lines. They knew and saw that these emaciated figures were not treated “right”. (I had the honor to meet two survivors of Theresienstadt in 1984 visiting my history class and listen to their memory of this visit in 1943).

When Mr. DuBois writes an essay in 1943 he does know something is done to Jews in Germany that exceeds “taking their civil rights away”. He might not know details. But to a black American writer of his level of sophistication some of the extend of brutality of the German government was apparent even if he didn’t know details of the camps. The concept of oppression does not start with a concentration camp, but its potential to lead to such brutality must be known to an intellectual and highly educated black American in 1943. I would even go further and argue that to an African American in 1943 a concentration camp does not “trump” slavery. Thus DuBois’ analysis might not have been much different after the war. And lets not forget that anybody with even a shade darker than white skin was suspicious to Hitler’s regime and would have a similar destiny than Jews and many others that didn’t “fit” the party line

The death camps were known facts before the allies reached them and opened them. But they didn’t fit into the narrative of a Germany, a white European country, that the allies had for the longest time business deals with, even into the war, and, of course again after the war. It didn’t fit into the admiration of Germany by people like Lindbergh that threw theories around about a grand German society while gathering at a Friday night dinner party in the 30s.

Denial does not equal “unknown facts”, but it provides bliss for generations to come not to revise their statements and actions from previous times or give justice to the victims of these regimes and societies.

Michaela, I stand by my application of “then unknown” unless of course you suggest DuBois was somehow more aware of what was happening in the concentration camps then the general public of the United States in 1943. This does not make him complicit in the Holocaust as you would seem to suggest the entire free world was.

As for the institution of slavery in America, everyone full well knew what was happening on the plantations. Harriet Beecher Stowe did not reveal a “then unknown”. There was no ignorance of the nature of the slave/master relationship in its extremes, and the vast majority of white Americans (just like the Europeans of the day as DuBois points out) believed they were the supreme race. This was never hidden before and after the Civil War, and was applied equally to the attitudes against Native Americans, the Chinese, etc..

Unfortunately, the history of the world is rife with inhumanity and cruel, barbaric practices, usually driven by a desire for wealth and power.

I did not just suggest that the entire free world was complicit, I did say their actions show that they indeed were complicit in many different degrees and shades. That does not take the main responsibility away from Germany.

To think that Ms Beecher revealed nothing new to Americans, while the opening of concentration camps was something entirely new to a large majority of Germans is absolutely wrong. They might not have known that Jews were killed in gas ovens, or that their bones filled German Autobahn constructions, but they knew they were killed, tortured and didn’t just go on “vacation”, when they disappeared.

My understanding is that designs for the autobahn were drawn during the Weimar Republic, but it was the Nazis who implemented them and to a certain extent they were used as cover for relocation of “workers” to “camps” that were part of a nationwide public works project. Grand Coulee, Hoover Dam, TVA and numerous improvements to national parks in the U.S. required relocation of workers to work camps through WPA and the CCC during the Great Depression when vast numbers of the previously indigent population found low wage manual labor on major government construction projects. The German masses were quelled to a certain extent with the “belief” that the Nazis were doing something similar.

Thomas Wolfe suspends his narrative for You Can’t Go Home Again between two pillars, describing trips he made to Germany, one in 1923 when he was beaten up by brown shirts in Munich at Oktoberfest during the infamous Beer Hall Putsch, the other a visit in 1936 to Berlin where he watched Jessie Owens and Ralph Metcalfe compete and win in the Olympic Games.

The final section of the book describes a train ride in a passenger compartment with five other travelers, one of whom departs the train, courtesy of the Gestapo, as they are changing engines on the German side of the border with Belgium. Only after they had crossed the border on their way to Paris did he get an explanation for what had transpired from one of his traveling companions. Anyone taking more than ten marks out of Germany had to explain their action on a customs form in advance or face serious consequences. Their fellow traveler wasn’t arrested for being Jewish. He was arrested for breaking the law.

Wolfe died before the war in Europe had even begun. His book was published in 1940, a year or so before Japan furnished something a little more definitive than the suspicions Wolfe raised about something not just sinister, but deeply evil, he had seen at work in the Nazi psyche.

The passage from Dubois on Reconstruction in Europe after WWII could almost be read as written in reply to Wolfe. North Carolina was the home to which Wolfe was saying he had learned he couldn’t return.

Thank you, Craig.