Like many of you I was sad to hear of the passing of historian Eugene Genovese earlier today. I was never formally introduced to the historiography of slavery in graduate school; rather, I relied on various friends and other contacts to point me in the direction of important studies as my interests both widened and deepened. Genovese’s name continued to appear and it was just a matter of time before I read Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made

Like many of you I was sad to hear of the passing of historian Eugene Genovese earlier today. I was never formally introduced to the historiography of slavery in graduate school; rather, I relied on various friends and other contacts to point me in the direction of important studies as my interests both widened and deepened. Genovese’s name continued to appear and it was just a matter of time before I read Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. It took me a long time to read it and even longer to begin to understand it. I find myself continually going back to it to review sections and even individual sentences.

More recently, I’ve been reading and contemplating his most recent book, Fatal Self-Deception: Slaveholding Paternalism in the Old South, which explores the intellectual world of slaveholders during the antebellum period and through the war. The book briefly explores the slave enlistment debate and Genovese even offers a few thoughts specifically about camp servants, which is my current research topic. The following sentence is one that I’ve been struggling with for weeks. It beautifully captures the complexity of the slave – master relationship in the midst of war.

Body servants may have had as strong a desire for freedom as other slaves, but their fidelity to particular masters cannot be gainsaid. (p. 141)

Genovese forces us to acknowledge that freedom and fidelity were not mutually exclusive desires among this particular group of slaves. Both the modern day Lost Cause apologists and those who would deny any feelings of loyalty harbored by slaves cling to a one-dimensional view. The interesting question for me is how camp servant and master negotiated the dangers of camp life, march, and battle and how that resulted in a certain set of expectations between the two and a great deal of disappointment specifically for the slavemaster as the war progressed.

He will be missed.

Eugene Genovese besides being a contributor to “Chronicles” magazine and “Southern Partisan” magazine was well known for his bigotries, in particular his attitudes towards gays and Lesbians.

He was a supporter of the neo-Confederate movement and the notorous M.E. Bradford.

He was in such disrepute in the academic community for his crackpot theories that the “Canadian Review of Americans Studies” asked why he wasn’t a part of our paper on Confederate Christian nationalism and gave us 1,500 words above and beyond their normal word length limit for articles to include him in our paper and writeup his support of Confederate Christian nationalism.

In one of his essays he has the gall and audacity to criticize Martin Luther King for not taking pro-slavery theologist James Henley Thorwell seriously.

Worse than all of the above was his writings, which I extensively read, he would frequently make an assertion about the South and then go on and on whining for paragraphs that those who didn’t agree with him with anti-Southern rather than actually supporting his assertion.

Typical Sebesta. I don’t think anyone is going to take this seriously. This is as bad as those Neo-confederate rants you take such pride in challenging.

Genovese should be credited for pointing out the complexity of the human inter-actions under slavery.

Still, Genovese came rather close at times to celebrating the mores of the Slaveholders, whose paternalism, he seemed to feel, represented a refreshing break from capitalism. How the heck he became so honored by conservatives still puzzles me.

I am reading Ron Chernow’s Washington and see that even this truly great man, who in many ways saw the need to end slavery, and who had very close and respectful relationships to some of his slave body servants, would still be shocked, hurt, and vindictive when his slaves tried to escape to freedom.

Kevin

On another note, who is the absolutely best living lecturer on the impact of the civil war on the American Constitution?

(I assume you have my email from this post).

thanks,

Tom

I don’t know about absolute best, but I enjoy listening to Mark Neely.

He sought the truth.

Not to simplify but is this something like a version of Stockholm Syndrome?

At a Historical Society conference about ten years ago, I gave a paper on the theologian Robert Lewis Dabney and his relationship with Stonewall Jackson. The first hand up at question time was Prof. Genovese’s. He said, “Can I ask a smart-ass question?” I said, sincerely, that any question coming from him would be an honor. Genovese responded, “oh, that’s what they say when you’re old.” I wish I’d thought to say, “no, that’s what they say when you are a great historian.”

Film director Ang Lee touched on the body servant subject in the George Clyde/Holt relationship in ‘Ride With The Devil’, diluting it by making Holt already free. I guess, in reality, the situation could vary, from something like an Imperial British Officer’s treatment of his lower-class Batman to the kind of brutal indifference shown to Concentration Camp house servants in, say, ‘The Boy With The Striped Pajamas.’ The state of mental denial necessary to justify bondage would always make genuine, untainted friendships impossible. If normal human empathy was not suppressed at every level for hundreds of years, the ‘peculiar institution’ could not have lasted a single day. Very limited and ambiguous social interactions had become ‘normal’ in this sociopathic system, with overt power all on one side and veiled survival strategies on the other. We continue to live in the aftermath of this poison.

This is the first I’ve heard of this. I’m deeply saddened by this news. I’m honestly at a loss for words. Elizabeth passed just a couple of years ago, didn’t she?

That’s a great quote.

It’s not a coincidence, though, that the majority of “black Confederates” cited today filled similar roles as personal servants of one sort or another. The key is that there was usually a personal relationship of one sort or another between those men, and it’s often the case that we know of their existence and activities through the writings and reminiscences of the white men they served. This is generally true of accounts of enslaved persons whether in a civilian or military context; we hear accounts and description of those most immediate to the slaveholder and his family. What you don’t come across often are wistful wartime reminiscences of enslaved persons who worked in gangs — often hired from plantation owners by the coffle, along with their civilian overseers — to repair railroads, build fortifications and the like. Yet those men undoubtedly outnumbered the close and familiar personal servants by several multiples.

The mistake that heritage folks make are several. First, they mistake friendly and familiar interaction between servants and their masters as evidence of a peer relationship — something that it could never be, regardless of how friendly it was. Worse, they sometimes take the experiences and friendly relations with family servants as representative of the whole. One online slavery apologist recently opined that in the South “blacks were integrated into society through the family, i.e.; the plantation household.” Somehow I don’t think the 101 slaves working on James Hawkins’ sugar plantation in Matagorda County in 1860 felt particularly “integrated into society” as part of the extended Hawkins family. We know those men, women and children existed by the census of that year, they they remain (literally and figuratively) mostly anonymous to us.

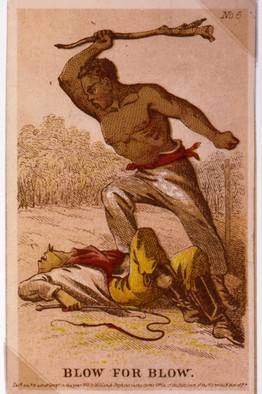

It’s this focus on (relatively) happy, warm interpersonal relationships that developed in the last decades of the 19th century — the “faithful slave” — that pervaded the way white Southerners chose to look at the institution of slavery, and depict it as a flawed but largely benign institution. It’s been carried forward for more than a century now.